Advertisement

A scientist's rapid COVID tests never made it to the public. Here's how that shaped the pandemic

Read the piece on Irene Bosch titled "This Scientist Created a Rapid Test Just Weeks Into the Pandemic. Here’s Why You Still Can’t Get It" here.

In March 2020, right at the start of the COVID pandemic, an MIT scientist and her team developed a cheap, rapid COVID test. It provided results in just 15 minutes.

But the test never made it to shelves.

"It's just tragic that so much capacity in terms of science is being wasted sitting in a lab or in a basement," Irene Bosch says. "It could have been a different story."

And it could have made all the difference in some of America's hardest hit communities.

Today, On Point: Rapid tests may be hard to find now, but they could have been available almost 2 years ago. We've got the story about why that didn't happen.

Guests

Dr. Irene Bosch, visiting scientist at M.I.T. and an adjunct professor at Mt. Sinai University in New York.

Also Featured

Mass. residents Grace McKinnon, 68, and Jorge Amaya, 23, voices from the Chelsea rapid testing site.

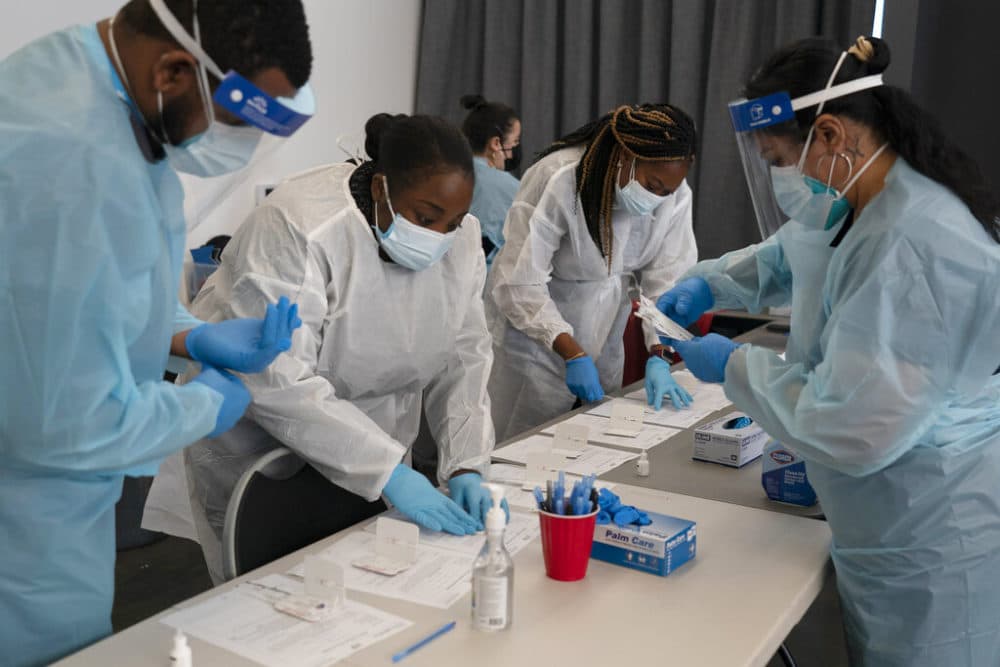

Show Highlights: How The Chelsea Project Works To Fight The Spread Of COVID-19

GRACE McKINNON: How far up are we going? OK. [Laughs]. It's a massage.

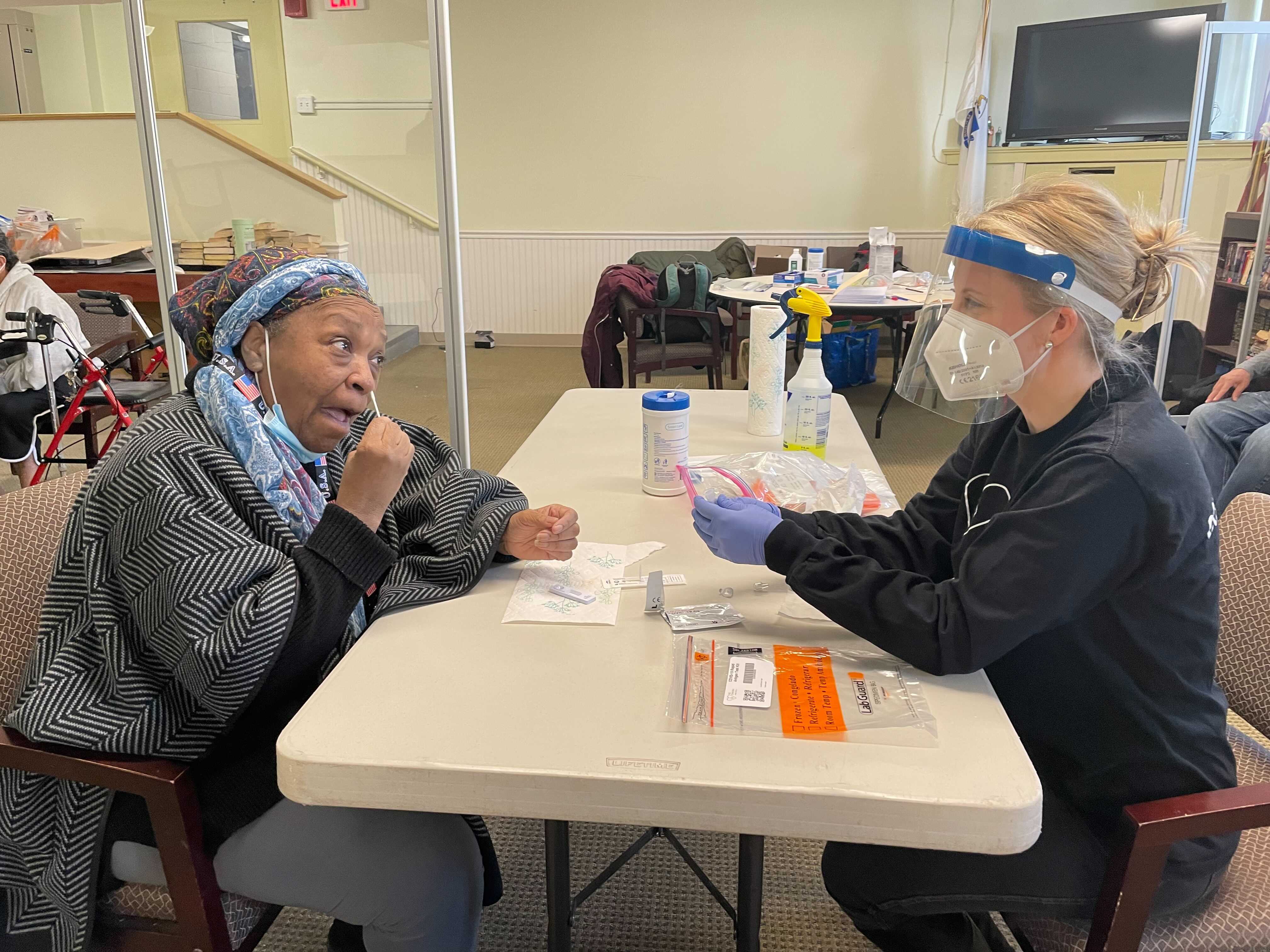

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Grace McKinnon is 68 years old. She lives in senior housing in Chelsea, Massachusetts. And that warm, wonderful laugh comes as she swirls a cotton swab in her nose, and is then shown how to dunk the swab into a plastic vial.

LAURA HOLBERGER, The Chelsea Project: Put the swab into the liquid here, and mix it up and squeeze it out, and we'll dispose of the swab.

CHAKRABARTI: Grace is getting a COVID rapid test, but unlike many other Americans, she didn't have to wait in line for hours or scramble from pharmacy to pharmacy to find that rapid test. Grace didn't even have to leave her senior housing building.

McKINNON: Easy. I was on the fifth floor. I came down to the first floor, walk down a hallway. That was it.

CHAKRABARTI: The free rapid tests are being offered by the Chelsea Project, a nonprofit working to reduce the spread of COVID in this Massachusetts city.

Advertisement

Chelsea is one of the most densely populated urban areas in the country. More than 40,000 people live within just a couple of square miles. More than 60% of them identify as Hispanic, and more than 80% of the adults in the city are categorized as essential workers. All of which is to say, back in the earliest weeks of the pandemic, Chelsea got hit hard.

In April 2020, the city had one of the highest infection rates in the entire nation. Six times higher than the Massachusetts state average, and even more than the infection rate during the worst days of 2020 for New York City. Which is why now, in January of 2022, the Chelsea project is working hard to make rapid tests available. And teaching everyone, especially the elderly and disabled, how to use them.

Laura Holberger shows Grace McKinnon how to read that little strip from her rapid test.

HOLBERGER: So now what we're looking for here is one line or two lines, so you keep an eye on that for me.

McKINNON: Long time since I looked for one line or two lines.

HOLBERGER: It's like a pregnancy test. Oh, you've got that right, exactly.

CHAKRABARTI: Grace McKinnon also has lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease, putting her at higher risk. And this week, she's even more vulnerable.

HOLBERGER: In the last two weeks, have you been diagnosed with COVID-19?

McKINNON: No.

HOLBERGER: Have you been in close contact with anyone diagnosed with COVID-19?

McKINNON: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Grace waits for her test results, but only for a few minutes.

HOLBERGER: You can see now that there's one line at the control, that means you're negative. That's negative. Okay? Two lines would be positive.

McKINNON: I love negative.

CHAKRABARTI: Grace plans to come back next week, and the week after that for more free tests, as long as they're being offered. But without this resource in her building, Grace says she couldn't afford to buy weekly rapid tests. And waiting for a PCR test just isn't an option.

McKINNON: Well, the old fashioned way is to go to a site and usually the lines are long. And the problem is it's winter in Boston, OK? You're already going to a site where people suspect that they're sick. And the elders, those in wheelchairs, the young families with kids, how do they manage that?

CHAKRABARTI: Recall, the City of Chelsea suffered greatly in the first pandemic wave in 2020. It might be happening again with the omicron variant. According to Massachusetts data, the city currently has the second highest positivity rate in the state. But catching COVID early is what health officials say will stop that spread. And that's exactly what happened with 23-year-old Chelsea resident Jorge Amaya.

JORGE AMAYA: At the beginning of this year, we all got COVID. And many of us were not showing any symptoms. Many of us just had a little cough. Me, I had a fever. I was the one showing the symptoms. Without those COVID tests, without the rapid COVID tests, my mom, for example, my aunt, they probably go out to do their regular daily basis things.

CHAKRABARTI: And like the majority of the workforce in Chelsea, Jorge's mom is an essential worker.

AMAYA: My mom is actually a lunch lady for the high school. So her catching COVID, and her not showing no symptoms ... just imagine if she goes to school and then she's giving food to the students in Chelsea. She's a substitute for that, so she goes to every single school in Chelsea. So her, she was showing no symptoms and she could be spreading the virus to every single student in Chelsea. So just me having the COVID rapid tests just prevented that from happening.

CHAKRABARTI: Chelsea City officials hope that with greater access now to these frequent rapid tests, Jorge's story can become the norm. But here's the thing, right? We are entering year three of this pandemic. The City of Chelsea reports that more than 12,000 people have had the disease so far, and hundreds have already died. So many people, like Alexandra Jimenez, who manages Grace McKinnon's building, are asking the obvious question.

ALEXANDRA JIMENEZ: I lost a lot of tenants, and when you work with the elderly, you become very attached to them. And I think if this will have been done when all this started, a lot of my tenants would be here. This should have been done from the beginning, I believe. I know cost money and and everything, but I think a lot of lives would have been saved.

CHAKRABARTI: While Chelsea, Massachusetts is moving forward now, the fact is back in March 2020, in the earliest weeks of the pandemic, more lives could have been saved by the exact same kind of rapid test that Grace McKinnon used this week, and that the Biden administration says it will soon distribute nationwide.

In fact, a COVID rapid test like that did exist back then. A cheap, at-home rapid test that provided results in just 15 minutes. But you never heard of that test in March of 2020, did you? Neither did I. In fact, it never made it to the shelves. And we may have never known about it, were it not for a remarkable report from ProPublica. Read that report here.

This program aired on January 12, 2022.