Advertisement

Is it time to abandon the ‘tough love’ approach to addiction?

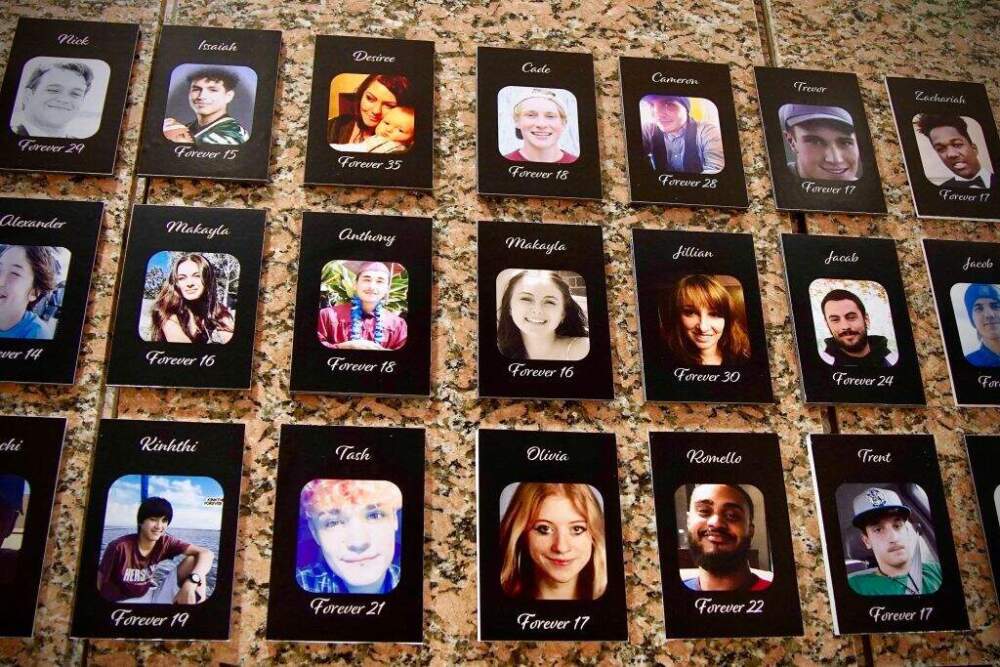

With the number of drug overdose deaths in the U.S. at record highs, many say drug addiction treatment needs to change. Some say the focus is already shifting away from punishing drug use to supporting someone’s efforts toward recovery,

"The old school model of addiction treatment has really focused on this model of moral failing ... and we know that that’s not correct. And what that’s created is a whole lot of stigma around a treatable chronic health condition," says Alicia Ventura.

Today, On Point: Is it time to do away with the "hit bottom" approach?

Guests

Alicia Ventura, director of Special Projects and research for Boston Medical Center's Grayken Center for Addiction Training and Technical Assistance program.

Betsy Cocos, Milwaukee resident and mother.

Reuven Cocos, Milwaukee resident and son.

Transcript

Part I

DEBORAH BECKER: What do you do if a loved one is addicted? It's a question now facing millions of Americans who often get mixed messages about how to help someone struggling with addiction to drugs or alcohol. Many families across the country are desperately researching treatment, counseling, retreats, medications, support groups, hoping for solutions to a problem that only seems to get worse every year.

As overdose, death rates skyrocket, and more potentially fatal chemicals permeate the nation's robust market for illicit drugs. Solutions are not only hard to find, but they can vary. Does someone need to quote "hit bottom" to stop using drugs and alcohol? Do they need tough consequences to stop? Or for some, is it more effective to use a softer approach that tries to guide the person away from substances and support them in the process?

Some parents especially say they've had to take difficult steps.

NANCY VERICKER: Once things really got bad at home, we had our son arrested.

Advertisement

BECKER: That's Nancy Vericker who told the Today Show in 2018 that it was only after that arrest that her son JP went into treatment.

VERICKER: When he got out of treatment, we said, "You have to stay," in treatment was down in Florida and we said, "You have to stay in Florida."

You can't come home. You're going to go to a halfway house and if you don't go to a halfway house, you're going to be homeless. So I really had to enforce that. Someone said to me that Christmas, that JP was homeless, and he was calling us every day in Florida. We hadn't seen him for seven months.

He was asking us to wire him money and a very close friend in recovery said that leaving our son in Florida at Christmas, just leaving him, no food, he said, "I'm hungry."

"Sorry." Click. Was the most loving thing to do. (APPLAUSE)

BECKER: Nancy said pushing her son away was the only thing that worked, and it helped him get sober. That tough love advice was also offered to Ken Feldsteen of Massachusetts when he found out his son Brendan was addicted to heroin. Ken says he and his wife were told, if you're supporting or in any way helping a child who's actively using drugs, it's almost as if you are the one putting a syringe into your child's arm.

KEN FELDSTEEN: So big gulp of that Kool-Aid, and it sounded very reasonable. Because nothing we were doing was working.

BECKER: And still, despite living on the streets and several stints in treatment, Brendan didn't get better. So Ken made a shift and decided to welcome him back into the family and support Brendan.

FELDSTEEN: He didn't get any better when we made the decision to not let him stay at the house, and he could have died. So I landed on love. I still feel that love wins.

BECKER: And that love from his family. Brendan says, put him on the path to recovery.

BRENDAN: I decided in that moment, never again, not doing it anymore.

BECKER: More addiction treatment providers are now recommending that families ditch the tough love and focus on just love. I'm Deborah Becker. This is On Point. We're going to wade into the addiction treatment debate a bit this hour, starting our conversation with a researcher who is recommending a different approach for those helping loved ones struggling with substance use.

Alicia Ventura is an addiction researcher and director of special projects and research for Boston Medical Center's Grayken Center for Addiction Training and Technical Assistance. Alicia, welcome to On Point.

ALICIA VENTURA: Thanks so much, Deborah. Happy to be here.

BECKER: So let's start with the fact that there is this body of advice out there that tells folks that people really should allow loved ones to hit bottom and there should be tough consequences.

How prevalent is that, would you say right now? And why? Why is that the main bit of advice?

VENTURA: Sure. So unfortunately, ideas such as hitting rock bottom, practicing tough love, accusing families of enabling are things that are quite prevalent in today's society. They're messages that families receive all the time.

And in the U.S., there's a really long history of blaming family members for their loved ones, problematic alcohol or drug use. And this goes all the way back, to the 1800's. So the way we as a society think about addiction shapes how we think about family members and close friends of someone with a substance use disorder.

So if we inappropriately assume that addiction is a choice and represents a moral failing, then it's natural that stigma gets extended to the family who also must be morally corrupt or dysfunctional in some way. And of course, we know that addiction is in fact not a moral failing, but a chronic medical condition.

And yet this discrimination against people who use drugs, and their families lingers. And that's what leads to these harmful myths in society, such as the idea of codependency, enabling, and rock bottom is that at the core, we still haven't accepted that addiction is in fact not a moral failing.

BECKER: There are books written about codependency and enabling, are those things just not true? Are you saying.

VENTURA: So it's not to say that those concepts have not been helpful to some people throughout history. You know when this idea of codependency developed it filled a void that existed in helping families understand what they were experiencing.

So family members who were impacted by addiction at the time, they were having these very difficult relationships. They were experiencing all of this stress and strain, and no one was really focusing on it.

So when this idea of codependency was proposed, it helped families feel like, okay, I'm not alone and this is a way that I can describe what it is that I'm going through. However, just as our understanding of addiction and substance use disorders has evolved, so has our understanding of the family and social supports and the dynamics that exist there. And so this idea of codependency is really more of a pop culture phenomenon than it is anything that's actually rooted in the empirical evidence.

And now when we talk about codependency, it's really more of a stigmatizing label that gets placed on family members where, you know, instead of acknowledging the sacrifices that they are making and their very, very natural desire to help the people that they love, we're saying that there's something wrong with them and that they have a disorder that is creating issues both for themselves and their loved ones. It's a really simplistic generalization of a very complex issue and set of dynamics. So has it helped some people? Yes. Would I encourage that we continue to call people codependent, which of course then leads to this idea of enabling? Absolutely not.

It's very harmful to family members and it's just not accurate.

BECKER: So what would you encourage? What's the alternative?

VENTURA: Sure. This isn't a black and white issue. It's gray. There's a lot of nuance. Family members themselves are greatly impacted by a loved one's substance use disorder.

And there are high-risk population who's deserving of care and support and education and evidence-based services in their own right. We know that family members who are impacted by someone's addiction have much higher rates of mental health and physical ailments than family members who are not impacted by a loved one's addiction.

So these are people that really, need care for themselves. In addition to tools for helping their loved ones. It's not about families, about asking families to prioritize care for their loved ones over their own health, and well-being, it's about providing resources so that families are able to care for both themselves.

Their loved ones who are struggling. It's not natural for most families to kick a loved one out or to turn their back on them when they're suffering. But they haven't been taught differently. They haven't been given other ideas or education about other ways that they can intervene. And so these harmful messages tell families that they're powerless and they're unhelpful because families aren't powerless.

They're incredible motivators of recovery and they're also empowered to take care of themselves. And providing families with the knowledge and support to be able to do what is best for their own family as opposed to incorporating any of this general advice, like you always have to kick your loved one out of the house.

If you are providing any sort of support or kindness, you're enabling their health condition. Like we just know this stuff isn't true, and so we need to help families to develop the skills they need to deal with this in their own way, which is going to be very different from family to family.

BECKER: Do you think though, that there's an infrastructure in place to be able to accommodate this more individualized approach?

Many families are dealing with things on a day-to-day basis. And they have to make decisions accordingly and things change. Is there support for them? And the person addicted, to be able to carry this out and make sure that they are in fact adapting as needed as a situation requires, which could change, right?

VENTURA: Absolutely. It's a great question. Deb, unfortunately our health care and addiction treatment systems have not been set up to support families or to take this sort of more holistic approach to caring for the individual. It's still very, patient centered, and families continue to be stuck on the periphery within these systems.

They're not valued for what they're bringing to the table. They're not recognized as these incredible agents of change, and they're also not being given the support that they need to take care of their own health and wellness. Just encouraging folks to start with challenging their assumptions about family members and about addiction and understanding, or trying to understand how that is ingrained in all of us and how it impacts the policies that we create.

The way that we interact with people can be very helpful, but this is a real need. Throughout the addiction and health care systems, we really need to be focusing more on families engaging social supports and recognizing these factors that impact really all health and all health conditions.

Advertisement

That aren't appropriately addressed when we're just focusing on the individual patient and not the greater context that they exist within.

Part II

BECKER: I want to bring in two family members now to share their story. Reuven Cocos and his mother, Betsy Cocos are with us from Milwaukee.

Reuven, Betsy, welcome to On Point.

REUVEN: Hi. Thank you.

BETSY: Thank you.

CHAKRABARTI: So I'm wondering, Betsy and Reuven, I understand you were listening to Alicia who was talking with us in the first segment of the program and she was telling us about incorporating families and making sure that we recognize the importance of this social construct when we're dealing with addiction in addiction treatment. And Reuven, what do you think of that idea? Do you, can you explain, you are now no longer using drugs. How crucial was it for you to have family support to be able to achieve that?

REUVEN: It was a make it or break it kind of situation. I wasn't, I had tried many times to do it on my own and I didn't have the words to ask for help.

There's a lot of pull yourself up by your bootstraps thinking going on in at least what I thought recovery was supposed to be. And so I never once thought to ask for help. And when I finally, I didn't even ask, I just kind of rolled up on my parents' doorstep, basically like in a burlap sack, with a lot of problems.

And they helped me. Jeez, I couldn't even, I couldn't function. So I had, they had to push me and then I would get a little head start and then I'd fall back a little bit and then they'd push some more. And I guess to answer your question, they were instrumental in me finding recovery.

BECKER: So I guess some folks would say if you didn't know how to ask for help, Reuven, and you were in a state of mind that was incredibly difficult, maybe you needed really tight guide guardrails and tough consequences. And that really would've helped, as well.

As opposed to something that sounds as if it was much more supportive. What would you say to that? What do you think of this idea of let someone hit bottom, detach from them and that's the way they will eventually be led to recovery?

REUVEN: Jeez, I would've thought, why not both? At one point.

But I think having family help and having strong boundaries is what did it for me. I had, and it was a learning process. It was really everybody who wanted to participate in my recovery, had to basically take a similar journey of looking at themselves and doing the work. Because, Jeez I'm losing my words here.

BECKER: That's okay. That's okay. I just, I guess, so your family was what was important for you.

BETSY: And can I say something?

BECKER: You certainly can. Go ahead, Betsy.

BETSY: So I want to be real clear, I appreciate so much that he said boundaries because he came home in December, a decade ago, and it wasn't until February that he told me that he was a heroin addict, and meanwhile, from the time he came home till that, it was like having a crazy. Our household was crazy. And I just want to be real clear, I appreciate how he said again, the boundaries. Because we love, we embraced him with love, but we also had real clear, he needed to start doing something. I felt really, there's a lot I wanted say, but I think I better have a question from you.

BECKER: (LAUGHS) Thanks. What were the consequences? What were the consequences if Reuven kept using drugs? You say there were boundaries, were there consequences as well?

BETSY: So let me just say this. I'm a psychotherapist professionally specializing in trauma. So I know the lingo and the minute that it was personal, it's, I don't want him to hit bottom. Because there's no guarantee that someone's going to come back from bottom. And so I've been doing this for a little over 30 years, so that is the old thinking.

And when it was my son, it's, I don't want to repeat myself, there is no guarantee someone comes back from bottom. When Dan interviewed me, he asked, did I feel guilty? It's no, I don't have any guilt. He said, did I ever regret bringing him home or having him home? I said, no, but was I furious with him at times, frustrated with him, angry?

Absolutely. I went to Families Anonymous and let me repeat. It's an amazing organization. He'd say, Mom, go, make sure you go to the meeting. You're always better when you come back from the meeting. I can't tell you, he had, we had expectations and there was a lot of yelling because he's on the couch not moving.

Unbeknownst to me he's using. It had been a long journey and the person who said, love thy father. It's love, but it isn't just a simple love. It's love with so much support and guidance and clear boundaries.

BECKER: But as Alicia said, it's tough for families to get that support.

And Betsy, perhaps your background helped you feel confident that you were doing the right thing, right? That you didn't, you were going to not listen to that advice to hit bottom because you were concerned that bottom was the end. So I guess where do you get support? Is it from family support groups?

Do treatment programs need to change to include families more? Where do the families get support?

BETSY: I would, if you are asking me, I would say I love what Alicia is doing. I would say all of the above. We had a wonderful person whose son had gone the same journey as Reuven. She literally took me to different meetings in the city, in the county where I live, and she took me to Families Anonymous, and that's where I felt my home, because these are families that, for the most part, I can't speak for everyone, but this is so new.

This is not in their context of how they grew up, and all of a sudden, they have something going on in their home, which is they have no understanding of and they need to understand. I think a multi-pronged approach and really understanding, there are amazing families out there that are doing amazing things in spite of barriers that federal government, state government, city government, and social services put in the way.

So I love what Alicia's saying.

BECKER: Did you, Betsy, ever feel as if you might be enabling Reuven? Like how did you know what to do?

BETSY: Yeah, I appreciate Alicia saying, because in my profession as I'm older and bolder, there are so many words I just hate, like co-dependent doesn't exist and I so appreciate, she was much kinder than I am about that word.

There's a ton of words that my profession have used to harm people and I allowed myself to think of the word enabling. Because I felt like any decision that I made, Am I enabling him? And what I came to conclusion is I might be crossing that line. Let's hope I don't go very far, because I was constantly having that on my mind.

I don't want to not have this be helpful and instead be ultimately harmful to him. I get a little lost in all of these thoughts because what's helped proven so much in his recovery is he continued to take more and more control of his life. And I realized in the first, after the first few months and I'm not pushing religion or anything, but I'm just saying I remember stepping out late spring, early summer, and this is after the February information, and I just looked up this guy and said, God, I'm putting him in your hands because I can't help him, because we can't make him stop using.

And I had, even though I intellectually know that, I had to viscerally understand that. And so I put him in God's hands and that was a support. And I have good friends. And I stayed away from all the family and relatives who were not good and helpful. And — yeah.

Yeah.

BECKER: Yeah. yeah. And did you force treatment?

BETSY: I can't force anything except in my house. His job was cleaning and that's what I forced, is that he had to clean, I can't force treatment. He had to do it.

REUVEN: If I could interrupt.

BETSY: Yeah. Go Reuven.

REUVEN: I had to want. To get better.

And I did. I really did. And I didn't know how. And it was all the false starts and the trying and the continuing to fail and then trying again. That got the ball rolling. And they provided a background for me to be able to try different means of recovery and then fail. And then I still, I had a place to, I had food, I had a place to sleep.

I had people who cared about me and that was like, that was enough to help me to continue to want to try.

BECKER: So it provided maybe a degree of accountability to have those folks with you and feel cared about, right? Was that?

REUVEN: Oh, absolutely.

BECKER: Yeah. I can imagine.

REUVEN: In the middle of addiction, you despair is like the, I don't even have the word to describe it, but despair was like my thing.

And that's what I felt all the time, except for when I was high. And that was only a short amount of time before that went away and the despair came back.

BECKER: And so was it a combination then, Reuven would you say, of treatment and support and perhaps maturity and a lot of different things that really were most helpful to you?

REUVEN: Absolutely. It was everybody, at least in my, in our family and then the friends that were supportive of my recovery contributed and it was really. I remember one of the first moments where I was like, this is working, is I'd had a job and somebody spoke to me like I was a human.

Which when you're with your family, they can, it's one thing, but when it's a complete stranger, when you're in addiction for so long and all of a sudden, a stranger is treating you like you're not some crazy vagrant, it was just the most amazing feeling and I felt, which is when you're using drugs, you're numbing yourself. And so when you're sober, it's almost like your raw emotion is just flowing everywhere. And I had felt good naturally out of nowhere, and I was like, is this what life is like, feeling okay? And you're not having to get high to do it. It's like I could get used to this. And it was little moments like that peppered throughout the day or the week. It didn't happen all the time, but I liked that enough to want to keep trying.

BECKER: What's your advice to folks who are struggling right now?

REUVEN: Oh geez.

Just keep trying. Honestly, failure is okay if you learn from it. That's what, I have friends that are in recovery and early recovery and long-term recovery, and that's one thing I keep repeating. It's okay to fail. It's okay to have a couple of days of clean time, and then you have a slip. What's really important is to examine why it happened? What triggered you? What emotions overwhelmed you to convince you that you needed to use again? So that you can have an eye, you can keep an eye out and see it coming and learn how to walk around it.

And I really, I guess my best advice is to just keep trying. No matter what, life gets more challenging and jeez, I could talk for. I'm so sorry. Tongue tied.

BECKER: Yeah, that's okay. You've done a great, you've done a great job. Betsy.

BETSY: Yes.

BECKER: What would your main bit of advice be to parents and families?

BETSY: Oh my goodness. I don't know that I have best advice. Keep working at it and get support for yourself.

You cannot do this alone. And I'm not being paid to talk about Families Anonymous, but I got to tell you, that is what really helped me get sanity in our house, because when you've got someone in your home who's using. It's like up is down and down is up, and there's no demarcation between a truth and a lie.

And the whole thing makes everything feel so crazy and you need guidance. And find other parents and go to the people that are supportive and understanding and trust your gut and your instinct. You love this human being. And also have clear boundaries as far as expectations and things. Yeah. I don't know what else to say.

BECKER: It's beautiful. I want Alicia Ventura to weigh in here. She's been listening. Alicia, when you hear Betsy and Reuven's story and obviously it's a successful one, is this what you're talking about when you say perhaps we can shift the approach and when you're talking about the importance of family structure and treatment.

VENTURA: Absolutely. Betsy and Reuven, thank you so much for sharing your story. So much of what you have talked about really resonated with me and I think speaks very much to the importance of, and the ability of family to help people. I wrote down a few things here that really stuck out to me. And this idea of boundaries, I think is a really important one that families need much more education and information about.

And to understand that boundaries are not the same as tough love. You can implement boundaries coming from the most loving place. And it's important that we do. And relationship boundaries are important because it let's you as an individual be true to your own values and needs and protecting what it is about yourself that you know you need to progress as a healthy person.

Boundaries are not about inflicting punishment on another person or trying to control them. So I also really appreciated when Betsy said that she can control what goes on in her house, but she can't force treatment, and that's absolutely right. We can't force people into treatment, but we can help them get there by giving them hope, by giving them love. And Reuven, I was, I got chills when you said, someone spoke to me like I was a human. Because how that is so heartbreaking that you were not spoke to in that way for so long.

And I think that really illustrates how just these tiny pieces of positive reinforcement and love and support can make a huge difference for people and to give them maybe the motivation or the founding that they need to move forward.

Part III

BECKER: We heard from a family who has really had a lot of difficulty navigating this experience with addiction. And they say that it was support, it was love, it is really a restored sense of dignity that helped get someone into recovery. But there are others who think very differently about this.

And we heard from a gentleman, Peter Lyndon-James. He runs a program called the Shalom House in Australia. He describes it as the toughest rehab program in the country. Often, they don't even allow their clients to have contact with their loved ones at least to start. And he spoke on Sunshine FM in 2017 and he said, this approach is good for patients and their families.

Let's listen to a bit of what he said.

PETER LYNDON-JAMES: I specialize in showing families how they can protect themselves from a person who is actually caught up in a cycle of addiction. How they can calibrate themselves as a family, as well as the financial pressures that come on a family through a person's choices of using substances and drugs.

I show families how to close their wallet and only do what they need to. Not what they want to.

BECKER: And Alicia Ventura, I wonder, what do you think about this idea that families have to protect themselves? We did talk about the chaos that often accompanies addiction and then is put on a family trying to help a loved one with addiction.

I know we've mentioned boundaries, but do those boundaries in some cases, maybe not all, really need to be tough.

VENTURA: Interesting wuestion Deb, boundaries are really important, and each family situation is different. So of course, there are going to be instances where a model, such as the one you've described, might be appropriate. By model, where the family and the individual who is dealing with a substance use disorder are separate from one another.

But overall, we have to be really careful of these sorts of programs that are in this old school antiquated ideology. That punishment or more negative consequences are going to somehow lead someone into recovery or, help them to progress in their life as a comfortable and healthy person.

Again, the way that we define a substance use disorder, or rather the way that it's diagnosed, is not looking at the amount of a particular substance that someone is using, but rather the number of negative consequences that it's having on their life. So this idea that somehow increasing negative consequences is going to get someone to cease their drug use or alcohol use, knowing that the very definition of this disorder is continued use despite these negative consequences. It just doesn't make any sense.

And to implement a program like the one we just heard about in Australia. Where you're making an assumption about every single family that, you know, their loved one needs to be separated from them, implies that all of these families, number one, are doing something wrong or are somehow harmful to their loved ones, which I'm sure is not the case. And it also implies that they don't want to help their loved one. And that's the piece that I think really gets missed here.

It's not about helping me or helping them. It's that most family members really want to help their loved ones. This is normal. It is totally normal to want to help and support someone you love who is struggling, right? And to think that just telling a family member, okay, you know what? You need to go take care of yourself and leave your loved one to deal with their own pain and suffering.

To think that makes it so a switch is flipped, and the family member is all of a sudden emotionally and physically detached from that person, is just totally unrealistic. So it goes against this natural drive that families have, and I think it's really harmful to everybody.

BECKER: Yeah. We've heard from so many listeners about this, who really want to weigh in and share their stories. Grateful to all of you who have shared your stories, but I want to play a bit of tape from a listener who called in. This is Marjorie from North Carolina, and she had an eight-year relationship with a man who was addicted to drugs, and she said the addiction got worse and he became abusive.

And I think this has to be a really frightening thing for folks and a difficult thing to handle. But let's listen to Marjorie.

MARJORIE: There also needs to be an understanding that there's a lot of abuse that can also happen with an addict. And that might also be happening towards the addict from other family members.

And this also needs to be addressed and maybe looked at by an outside party before people attempt any kind of in-home treatment. Because he's tried rehab, he's tried methadone clinic. He's even had near-death overdoses and he tried in-home treatment with me. But I didn't understand anything about it until it was too late.

BECKER: Alicia Ventura how do you advise families to balance safety? And this almost goes back to one of the questions we asked at the beginning of the show. What kind of support is there for families to be able to make those judgments when it's beyond what they can handle at home and what they can support.

VENTURA: Sure. This is a really important topic. Interpersonal violence. We know that there's increased prevalence of this occurring in families where substance use is also present. And it is so important that families, of course, take the necessary steps to keep themselves safe. The way that we would encourage families to act if there was interpersonal violence taking place and substance use wasn't involved.

It's going to be up to each family, what their needs are, what they're able to tolerate. Of course, I would never encourage anyone to stay in a situation that is unsafe. One other interesting thing that this caller shared was that she didn't understand anything about the treatment that they were, whoever was suggesting take place in the home.

And that's another huge piece of this, is that family members not being engaged in treatment or not educated about what treatment looks like. Often rely on, again, these myths or these ideas in society. Like for example, that methadone is trading one drug for another, which, methadone of course is a gold standard treatment for opioid use disorder.

It reduces the risk of death by over 50% and it's one of the most effective medications in all of medicine. Yet it has the stigma attached to it and without information about what treatment looks like, families may find it very difficult to support their loved one in that treatment because it may seem counterintuitive to them.

BECKER: We also heard from Margie from Ohio, and she told us a story about her son John. John unfortunately died in 2022 after years of alcohol addiction. And she felt that she couldn't find anything that was effective. Let's listen.

MARGIE: We tried so many things. We did kick him out eventually.

He lived in his car. He lived on the street. He was homeless. He was arrested for being homeless. He managed to have some jobs in between there. He'd come home and then he, we'd kick him out if he was drinking. It was on and off, on and off for 20 years or so. So we tried tough love. It didn't work with him.

We tried embracing him and just accepting how he was, and that didn't work either as far as getting him to quit. So I think it's up to the person who has the drinking problem, they have to make a decision somewhere.

BECKER: Alicia Ventura, what do you tell folks who feel as if there aren't really many options out there that are working for them?

VENTURA: It's very heartbreaking to hear this story. And of course, this is the experience of, we know hundreds of thousands of families across the United States. The way that our addiction treatment system is set up, but also, the way that our society treats people dealing with addiction, unfortunately, doesn't lend itself to folks having an easy, straight path to recovery, whatever that means for them. But thinking about this idea of harm reduction for families. Reducing harm really to everyone. Like at its core it's about providing support and education to families to help them make decisions that fit their individual values and needs.

And it's also about helping families to understand that while abstinence is one possible outcome, it doesn't need to be the only outcome. Nor is it always going to be the best outcome or the best option for everyone. So sometimes, when we can, help families understand that abstinence isn't the only thing to celebrate, that there are lots of positive changes to celebrate, and that all positive changes can be celebrated, it can change the dynamic both for the person who is using drugs or alcohol, but also for the family because it's less pressure on them, right?

It's not you, your whole way of feeling about your loved one is impacted by this, whether they've used or not, but helps you approach the person in a more holistic way. Because anytime we try to define a person by one thing about them, one characteristic, it's really problematic and doesn't capture the human experience.

BECKER: So what would it look like very concretely? What would it look like if a family were to say, I'm not only going to celebrate abstinence, I'm going to celebrate what? Or how am I going to do it differently? I'm going to celebrate the fact that you made it to work on time today and you were responsible enough.

And even though you may have slipped we've got a little step here. What would it look like?

VENTURA: Sure. What might it look like? It might look like, just like you said, families celebrating things, like someone getting a job, making it to work on time, interacting positively with their loved ones, taking the trash out.

Just acknowledging that. Thank you so much. And, if someone is to have a recurrence or a relapse instead of at the bottom falling out and approaching it as this horrible disaster that no one can recover from, which is not going to be helpful to anybody. Talking to them about it.

Just saying, what does that feel like? What happened? Can you tell me what's going on for you? When we try to ask people about their experiences in a non-judgmental way. Instead of every question being, did you use today? Are you thinking about using and just obsessing over that when we can allow ourselves to take a step back and actually celebrate those little things. They amount to something much bigger.

BECKER: When folks who are addicted talk about being in the throes of addiction and real physical dependence, they often mention how manipulative they are. They don't like themselves. But they'll lie. Steal, do all kinds of things to try to get that substance.

I wonder how do folks learn how to deal with that and draw the line and make sure that the right boundaries are in place when you don't always have a reliable person that you're dealing with, at least before folks are ready to make a significant change.

VENTURA: Sure.

That's going to be, again, a very personal decision for each family and someone shared in a training I did recently that they felt like they were as honest as they could be throughout their recovery at that at any given time, which I thought was a really interesting way to describe that. There's people that aren't using alcohol and drugs who don't feel comfortable being open and honest about things that are going on either.

I think sometimes we have to make sure that we're not othering people with addiction. For each family that might be a boundary. If the person is stealing from that family, then the boundary is going to be about their actions and addressing it. But I think it also is helpful for the family to understand that.

This person is having these intense compulsions, to acquire that substance so that they can feel like a human. And that might mean doing things that they wouldn't otherwise do. And sometimes, the family can help with that.

BECKER: In our last minute, Alicia, I wonder, if folks decide that treatment is what's needed and wanted, what do you recommend that they look for in treatment?

Because as you've said, this is changing in addiction treatment as well, in some cases, but not all. What should they ask providers here now? We've got 45 seconds.

VENTURA: Sure. I think it's important that you ask. Whether or not there's evidence-based treatment available, and also how families are included in treatment, what resources are there available to families within the network. Or organization that you're looking to access.

And how families are involved as well as what the plan is for ongoing support.

This program aired on February 21, 2024.