Advertisement

The Power Of Person-To-Person Presidential Politics And Other N.H. Primary Myths

Resume

The New Hampshire primary campaign offers voters a rare opportunity to get a close look at the candidates vying for the presidency. Throughout its history, long-shot candidates, from Jimmy Carter to Gary Hart to John McCain, have used the chance to meet and greet voters across the state to launch successful national campaigns, and in some cases, go on to win their party’s nominations — even the presidency.

But the importance of personal face-to-face campaigning for which New Hampshire is so famous is sometimes exaggerated.

Across New Hampshire in this season, you can pick just about any day of the week and head to a local fire station, house party or VFW hall and get a close look at the candidates running for president. You can meet them multiple times, shake their hands — even ask them a question or two.

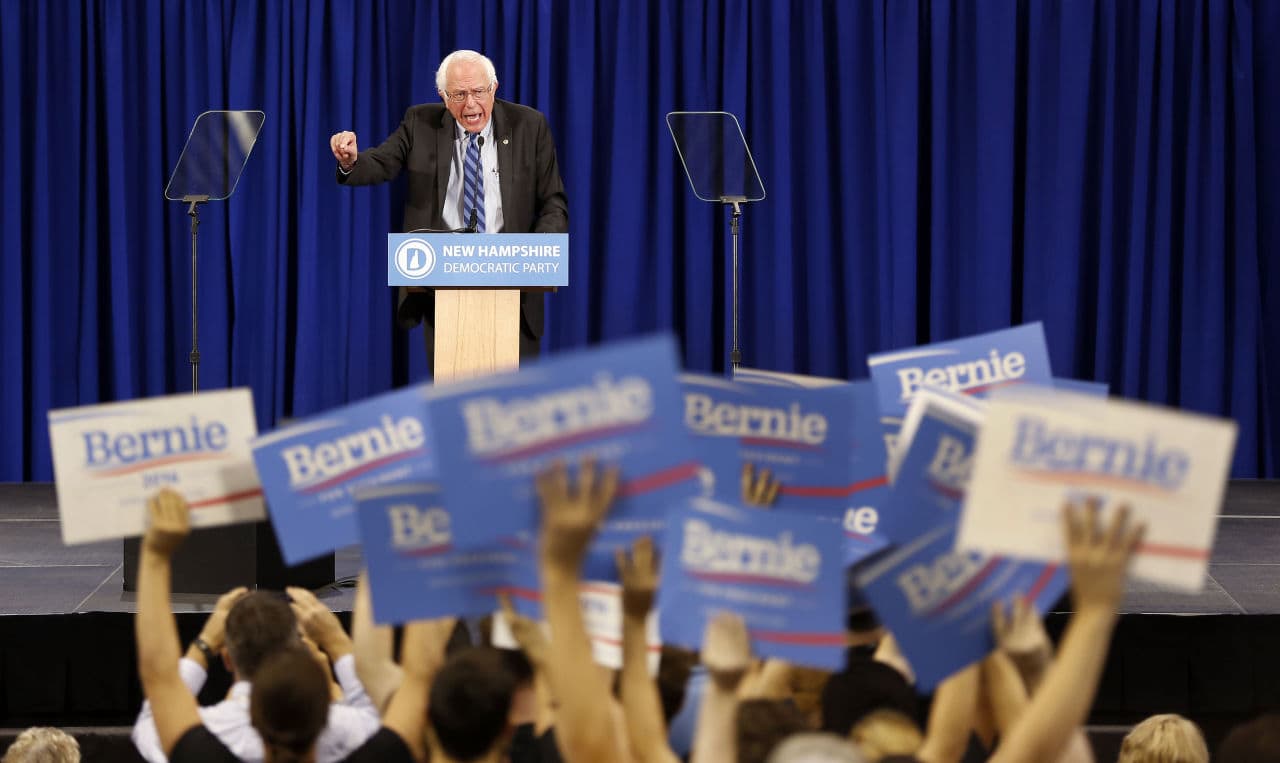

And all the candidates will tell you pretty much the same thing about the importance of the state’s first-in-the-nation primary. At a recent event at Nashua Community College, Democratic presidential candidate Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders said New Hampshire voters hold the key for his insurgent candidacy.

"If we can win in New Hampshire, we have a real path toward victory and pulling off one of the major political upsets in the history of our country," Sanders told an audience of students.

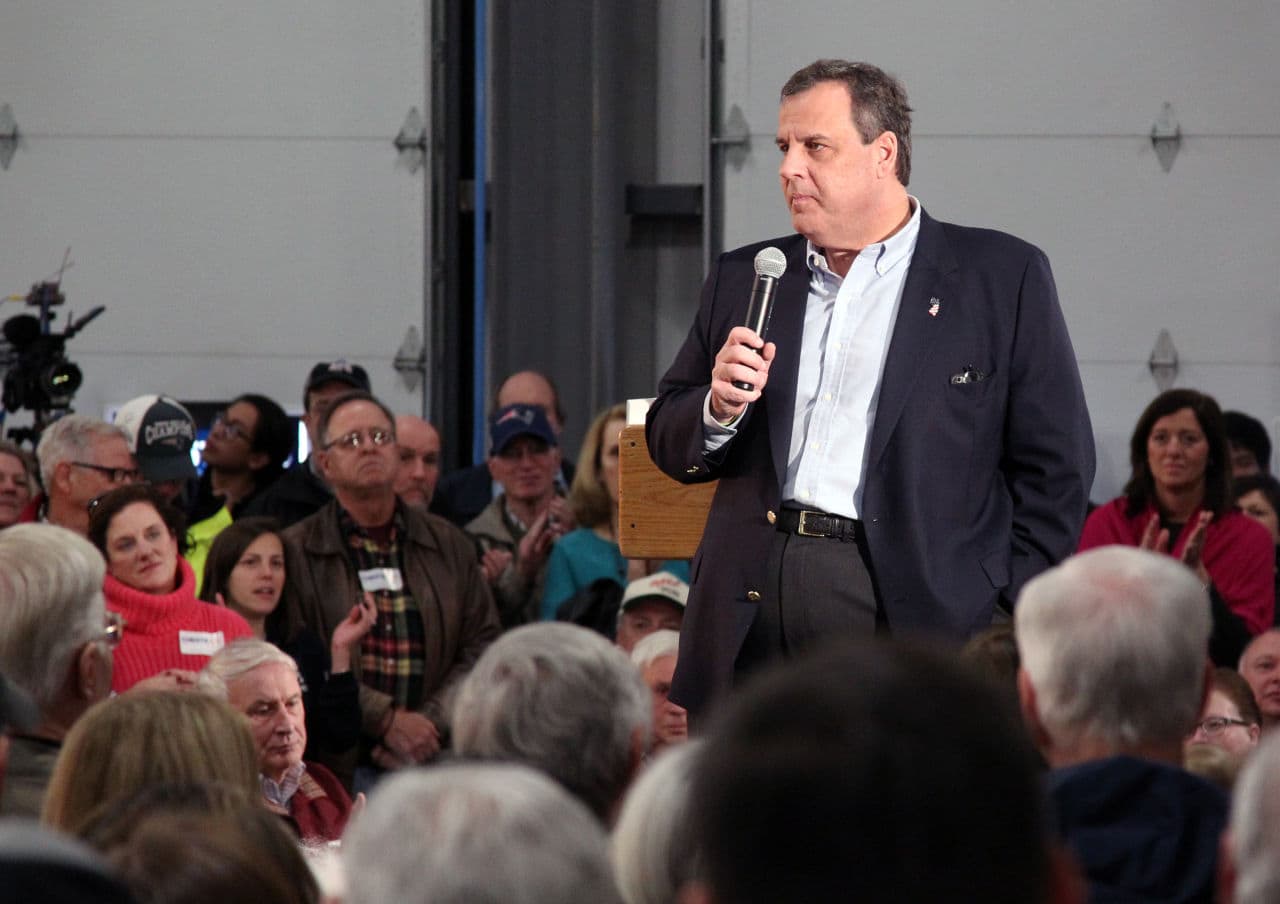

You will hear the same message from Republicans, such as New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie. At his town meetings, Christie seems to relish the chance to talk directly to voters — and to ask them for their vote.

“I don't want to be in your top three anymore,” Christie told a crowd who had gathered inside a fire station in Loudon. “They must teach that in school in New Hampshire, right? Every person tells me, ‘well, you're in my top three!’ I'm done with your top three, everybody! It's time to get to business! I'm asking for your vote on [Feb. 9].”

Christie has held about 40 town hall meetings in New Hampshire — more than any other candidate. According to national polls, his campaign is still lagging, but according to the latest survey from WBUR, in New Hampshire, he's climbed into second place behind Donald Trump.

Wayne MacDonald, the chairman of Christie's campaign in New Hampshire, says all those visits are paying off. MacDonald has some experience about the power of this kind of campaigning. Back in 2000, he was co-chair of McCain's first presidential campaign, when the Arizona senator practically moved to New Hampshire, held scores of town meetings and invited reporters aboard his campaign bus, the so-called “Straight Talk Express.” McCain won the primary that year, though he went on to lose the nomination to George W. Bush.

But eight years later in 2008, McCain used the same strategy to turn around his struggling campaign.

"His fundraising had fallen off, his political organization had suffered some major setbacks, and yet he was able to bring it back and win in New Hampshire,” Macdonald said. “And it brought him all the way to Minneapolis and the nomination of the party.”

McCain’s victory in New Hampshire sent a powerful message to his opponents. “We sure showed them what a comeback looks like,” McCain told a crowd of cheering supporters on primary night in New Hampshire. "And when they asked, ‘how you going to do it? You're down in the polls, you don't have the money,’ I answered, 'I'm going to New Hampshire and I'm going to tell people the truth!' "

Talking directly with voters in New Hampshire was an important component of McCain’s victory in 2008. But in truth, it was only one ingredient of his success; the hard work of grassroots organizing and campaigning began eight years earlier, during his first presidential campaign, when he held a record 114 town meetings across the state.

"What people sometimes forget is that the first several town meeting were attended by just a couple of dozen people. And sometimes they were bribed to be there with free ice cream," recalled Fergus Cullen, a former chair of the New Hampshire Republican Party and author of "Granite Steps: A New History Of The First-In-The-Nation Presidential Primary."

As McCain went from town meeting to town meeting, answering question after question, the crowds grew. "Over the course of the campaign, he did four stops in Peterborough, and the first one attracted something like 60 people, and then there were 300, and finally, there were nearly a thousand people," said Cullen.

That's the promise of New Hampshire: that a candidate can take advantage of all those face-to-face meetings with voters, and from there, launch a viable national campaign.

The most famous example of that was Jimmy Carter in 1976.

"I started my own campaign 21 months ago. I didn't have any political organization, not much money, nobody knew who I was,” Carter said in a political ad from that year.

The one-term governor from Georgia came to the state as a virtual unknown, and went to work “shaking hands talking to people, and listening," as Carter said in his ad.

"And the famous quote from him was, ‘hi, I'm Jimmy Carter, and I'm running for president,’ and the response was ‘Jimmy who?’ ” recalled Andrew Smith, a political science professor and director of the UNH polling center, who says Carter was the first candidate to use the New Hampshire primary so effectively.

"Nobody knew him, and he campaigned really doggedly [in New Hampshire] when no other candidate was really doing this,” Smith said.

But just about all candidates are doing it now, so Smith argues that it doesn't really give anyone an advantage. “It’s a wash,” he said.

According to Smith, this is one of the myths about New Hampshire — that under-funded, long-shot candidates can come out of nowhere, campaign across the state and achieve success like Carter or McCain.

“Campaigning here a lot is not going to win you the nomination,” Smith said. In fact, he argues that the candidates who campaign the most in New Hampshire are typically candidates who have no chance of winning. “So this cycle, the two Republican candidates who are campaigning the most are Lindsey Graham and George Pataki, neither of whom are polling above 1 percent. And the reason they're campaigning here is because they have no money to do any other kind campaigning,” Smith said.

According to Smith, what wins in New Hampshire is the same thing that wins nationally: money and organization, which are far more important than meet-and-greet grassroots campaigning. And by the way, if face-to-face campaigning mattered so much, how do we explain the success of Trump?

No matter what Trump says, it doesn’t seem to hurt his standings in the polls. At least not yet. Many believed that his proposal to slam the door on Muslim immigration would be a step too far, but it only strengthened his support, according to the most recent polls.

"We've got to get down to the problems — we can't worry about being politically correct,” Trump told a crowd of cheering supporters in Portsmouth recently.

Trump is, well, “trumping” the conventional wisdom that candidates need to engage with voters in New Hampshire. In his campaign, he is avoiding any New Hampshire-style campaign events, such as town hall meetings and other meet-and-greet events. Instead, he favors the occasional big rally, or events like his recent appearance in Portsmouth, when he flew in to accept the endorsement of the New England Police Benevolent Association, a union representing local cops and corrections officials, where Trump spoke for about 10 minutes, took no questions and was then whisked away in his motorcade.

"I don't think there are 25 people who have asked him a question,” said Cullen, the former state GOP chairman. “And if he's successful and wins the primary, he'll be the first candidate ever to have done that."

In fact, others have done it, but not for a while. Back in 1952, for example, when he was supreme commander of NATO, Dwight D. Eisenhower won the New Hampshire GOP primary without ever setting foot in the state.

There is another myth about the New Hampshire primary that has to do with the reputation of the state’s voters. As political reporters, we often talk to people like Debi Rapson from Manchester, a Republican, who showed up recently at a Jeb Bush town hall meeting in Hookset. Rapson still hasn’t decided who she will support, though she has narrowed her list down to the three governors — Bush, Christie and John Kasich — because she says governors “have actually run something.”

But Rapson says she has made up her mind not to vote for Trump.

"I think he's a radical. I don't think you can fire China if they don't go the way you want them to go,” Rapson said. “I think America is made up of a melting pot of people, and I don't think you can close out people just because of their religion, otherwise none of us would be here."

Rapson is one of those serious, well-informed New Hampshire voters, who attends multiple campaign events before making up her mind, and who candidates work so hard to win over. But Smith of UNH said the idea that the state is full of voters like Rapson is a myth.

According to Smith's surveys, only 10 to 20 percent of New Hampshire voters have attended a campaign event, which is a lot compared to most other states.

"But that means 80 to 90 percent do not attend campaign events,” he said. “Because most voters just aren't that interested in politics.”

In this season in New Hampshire, with all the candidates and their armies of political organizers crisscrossing the state, with all the rallies and town meetings — not to mention the thousands of hours of political ads on the airways — it’s virtually impossible to avoid presidential politics.

But the idea so prevalent in this season that most New Hampshire residents love politics is perhaps the biggest myth of all.

Correction: An earlier version incorrectly reported McCain's elected office in Arizona. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on December 21, 2015.

This segment aired on December 21, 2015.