Advertisement

Wild Turkeys In Brookline May Be Intimidating, But They Used To Almost Be Extinct

The ornery new residents are seemingly everywhere. They're chasing down letter carriers in Falmouth and attacking a pregnant woman in Cambridge. One in Revere got so good at stopping traffic, state officials forced him to move to the woods fifty miles away.

It would be easy to say Massachusetts has lost its war against wild turkeys.

But Matt Miller, director of science communications for the Nature Conservancy, looks at it in a different way. He believes the rise of the urban turkey is actually one of wildlife conservation's biggest success stories.

"Conservationists spend a lot of time worrying about elephants and polar bears, and even consider it hopeless. Well, at one point, turkeys were just as hopeless, or so it seemed," Miller said. "But then, they came roaring back due to a combination of hunting regulations and reforestation of parts of the country."

We very nearly killed off turkeys in North America, according to Miller. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were fewer than 15,000 left in the wild. The problem for turkeys is they're good eating and easy to hunt. So, for people living in a more agrarian America, shooting a turkey for dinner was a quick and easy way to lock down a meal. And what a family couldn't eat, it could sell.

"Wild game was very common in the finest diners in New York City, in Boston, up and down the East Coast," Miller said.

With turkeys dwindling to a small population in Michigan, the government stepped in. As Miller explains, regulations were introduced to limit turkey hunting. Plus, demographics were changing, too; people were hunting less in general, and game meat lost its market value.

Breeding turkeys in captivity didn't help restore the wild population because, accustomed to regular feeding and easy shelter, the birds grown in captivity couldn't hack it once back in the woods.

"People thought, 'Well, maybe turkeys' time [has] passed. They just can't adapt to humanity.' Completely untrue," Miller said. "When they caught wild turkeys and reintroduced them, they took off across the country because they're very adaptable. They'll eat just about anything. They'll eat frogs, they'll eat your backyard birdseed. It's hard to imagine a more adaptable bird."

"It's kind of tough to hunt a turkey in suburbia, and the turkeys know that."

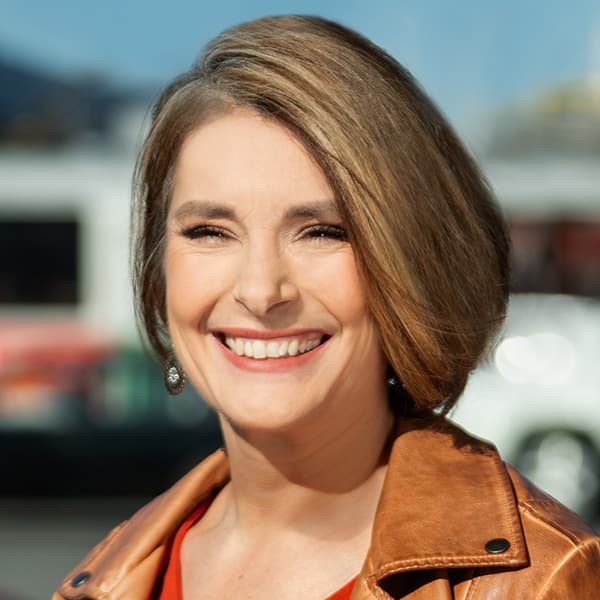

Matt Miller

Relocating wild turkeys started slowly, and eventually, the practice made its way up and down the East Coast.

"A colleague of mine calls it the great turkey shuffle," Miller said.

The wild turkey made its return to Massachusetts in the 1970s, when 37 birds were relocated from New York to the Berkshires, according to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. From that 37, there are now between 30,000-35,000 wild turkeys roaming the commonwealth.

Regulation and relocation may explain how wild turkeys found their way to the woods in the Berkshires, but how did they get to a town like Brookline, one of the densest suburbs in the country?

"It's kind of tough to hunt a turkey in suburbia, and the turkeys know that," Miller said. "It's mystifying to me that people will often refer to turkeys as being stupid. They really are not stupid birds. They know where to go to be safe, and they know where to go for food. And that last part can really get them in trouble with people. Sometimes they even turn aggressive."

Advertisement

That familiarity with humans has bred turkey contempt.

"Once they get used to humans, they basically consider humans part of their flock, and they want to put us in our place and show us that we aren't as important as we think we are," Miller said.

"The other part of it is that people are feeding turkeys, and sometimes they think it's cool if a turkey's eating out of their hands," he added. "But a general rule is it's always bad to feed a large, wild animal — especially one equipped with large, sharp spurs. Because then, when you don't feed them, they're going to take out that aggression on you with very poor results."

While the state recommends carrying a stick and showing dominance around wild turkeys, Miller has another suggestion: Cross the street.

"Don't try to get into it with a wild turkey."

This segment aired on November 25, 2019.