Advertisement

A look inside a lab studying fire in Worcester

Albert Simeoni has dedicated his life to fighting wildfires. While studying for his doctorate in mechanical engineering, he wanted to experience fighting the fires he was researching.

So he became a firefighter in Corsica, France, and real-life experience hit him fast — like the time he inhaled too much smoke.

“I laid down on the road because I couldn’t take it anymore,” he recalled.

Or the time he was trapped in a wildfire inside a canyon, and didn’t know if he would make it out alive.

“I heard my crew screaming for help and I couldn't help them because I was crawling,” he said. Luckily, they were rescued. But a year later, two firefighters died in the same canyon during a fire.

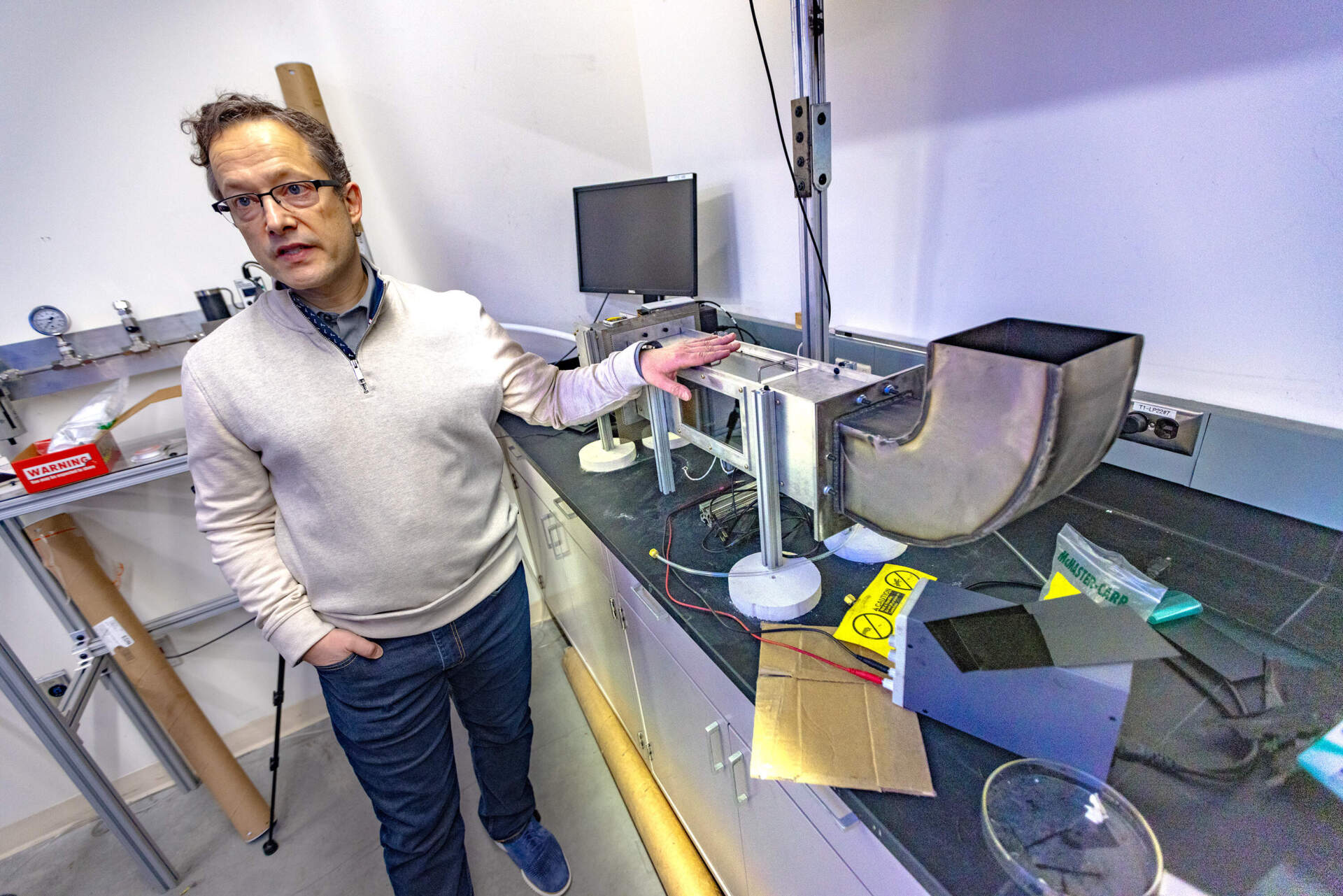

Today, Simeoni is an internationally recognized expert, professor and head of the Fire Protection Engineering Department at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, which is one of the leading fire research labs in the country.

As wildfires are getting more extreme, Simeoni is on the hunt for solutions.

Los Angeles residents just experienced one of the most destructive wildfire seasons in California’s history. Massachusetts itself had unusual wildfire activity last fall, with a record number of acres burned. His goal is to help prevent future catastrophes like these.

“We see the impact on people. You know, that's for us, that's really our driver,” said Simeoni.

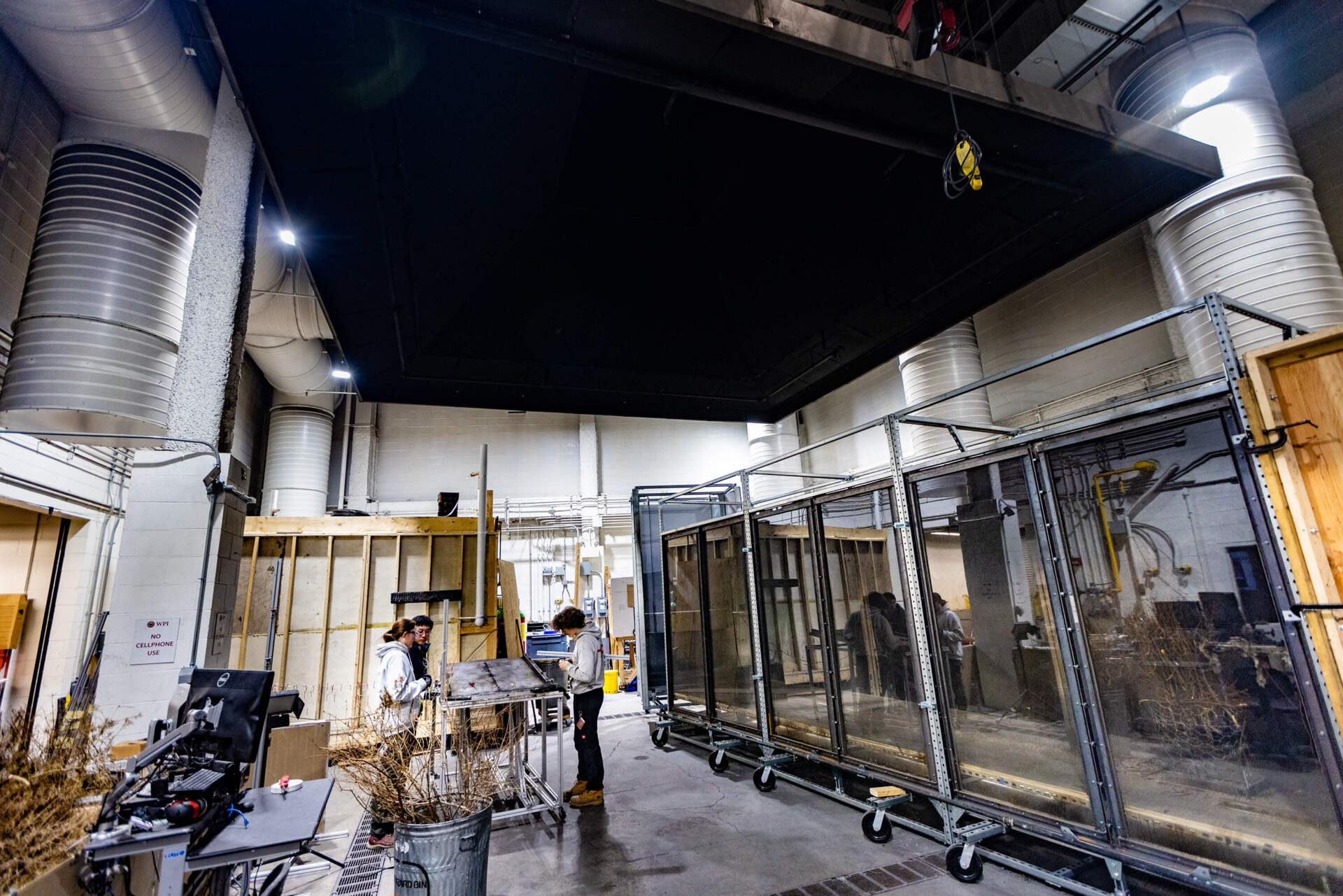

The lab is massive. Taking up 190-square meters on WPI’s campus, it features an exhaust hood so that the team is able to conduct large experiments. Simeoni said the team once burned an entire train car in the lab.

Simeoni and a couple graduate students huddled around a wind tunnel running the length of the room. It’s made of fire resistant steel so they are able to conduct burns multiple times a day. One side of the tunnel is fire resistant glass so researchers can see what's happening inside. On the far right end, there are two large fans able to create winds up to 40 miles per hour.

The wind tunnel allows the team to study fire under different conditions and to understand how to stop its spread. In the first experiment, the team burned a stack of pine needles to see how different wind speeds impact the spread of embers.

Embers can cause spot fires and light nearby buildings on fire. During the experiment, researchers tracked the number of fire embers created, their size and how far they traveled.

Advertisement

One variable that’s hard to create in a lab is climate change.

Fluctuating weather conditions, Simeoni explained, have created a “whiplash” effect. For example, since California had more rain than usual over the last few years, more vegetation grew. But then in a drought, the greenery became fuel for the wildfires.

Extreme wildfires doubled worldwide over the last two decades, according to a study of NASA satellite data.

So, Simeoni is focused on prevention and solutions. For instance his research team is updating fire safety codes, influencing building design, and writing fire fighting safety policy for government agencies and local firefighting departments.

“We love to play with matches in a safe environment. That's a lot of fun, but we do that with a mission,” Simeoni said. “We really want people not to lose everything they've built in their life. We don't want them to lose their life, or we don't want their health to be affected.”

One small piece of advice for everyone: Rake your leaves and clean your gutters.