Advertisement

At The Rose, 'Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect' Deconstructs The Life And Work Of An Iconoclast

Have you ever imagined taking a sledgehammer to a building, peeling back the layers to see what’s really under there, exposing what works and what doesn’t?

Gordon Matta-Clark did, slicing with abandon into warehouses and vacant buildings both in Europe and the United States. His cuts on buildings in the 1970s were to become the talk of the art world and would earn him a place in art history annals. In chopping through the layers of derelict structures around him, he exposed what didn’t work, not only in the buildings themselves, but in society at large.

Now, some of those iconic cuts can be seen in “Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect” a retrospective on view Sept. 21 through Jan. 5, 2020 at the Rose Art Museum. The show, organized by The Bronx Museum of the Arts (and curated by Antonio Sergio Bessa and Jessamyn Fiore), uses Matta-Clark’s “cuts” as a point of departure to explore the artist’s wider art practice, including his work with the homeless, his pointed social commentary and his interest in direct community action.

“Gordon Clark is one of those artists who’s iconic for the fact that he doesn't belong tightly in any category,” says Luis Croquer, chief curator at the Rose. “Some people say it’s conceptual — I don't think it’s conceptualism purely. Some say it’s minimal — it's not minimalism purely. It isn't architecture. Some people read it in very poetic terms. I think his practice is very hybrid and very responsive to the city, very responsive to people and time. What he was doing was trying to address how art could be a tool for change and how he could dismantle essentially some of the vocabulary that had previously existed in architecture and in arts too.”

In other words, Matta-Clark, who died in 1978 at the age of 35, believed in “creative destruction.” By carving into the carcasses of forgotten buildings, usually situated in neighborhoods where wealthier residents had fled for the suburbs, he could literally poke holes in architectural conceits like modernism, which he saw as precious. Modernism was functional and problem-solving, but Matta-Clark, in keeping with the general anarchic spirit of his times, wasn’t thinking about function. Rather, he was interested in “de-structuring” space in a way that simultaneously deconstructed the very political and economic systems that he believed led to the hollowed-out neighborhoods where he created his works.

“I have chosen not isolation from the social conditions but to deal directly with social conditions whether by physical implication, as in most of my building works, or through more direct community involvement, which is how I want to see the work develop in the future,” he said in an interview with architectural historian Donald Wall a few years before he died of pancreatic cancer.

Advertisement

“Anarchitect” offers a broad survey of Matta-Clark’s interdisciplinary work, mostly in photographs, prints and drawings but with a sprinkle of sculptures, including a building fragment from one of his cuttings. There is also an immersive film projection of his work.

“When you’re living in a city, the whole fabric is architectural in some sense,” Matta-Clark told Liza Béar of Avalanche Magazine in 1974. “We were thinking more about metaphoric voids, gaps, leftover spaces, places that were not developed.”

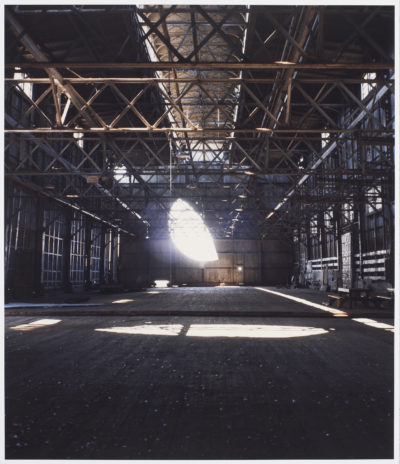

One of Matta-Clark’s most noted leftover spaces is “Day’s End (Pier 52),” in which he cut a huge crescent shape into the side of an abandoned warehouse near the Hudson River in New York City. He also removed part of the warehouse’s floor and roof, opening the interior to the sea and sky. The project (Matta-Clark called it his “sun and water temple”) took two months in 1975 and proceeded smoothly in the no man’s land across from a collapsed section of the West Side Highway until the City of New York finally discovered what he was up to. The city promptly sued the artist, but the lawsuit was eventually dropped.

“Conical Intersect” was made the same year as “Day’s End” for the Biennale de Paris. Matta-Clark carved a large cone-shaped hole through two 17th-century townhouses that were scheduled to be razed near the building site of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. In his own unique way, Matta-Clark had inserted himself into the middle of a social discussion, as the building of the center was controversial at that time. Other cuts presented in pictures include “Bronx Floors,” in which Matta-Clark took his saw to the floor of a Bronx building, allowing for dizzying views from one floor to the next.

In his period of cutting, Matta-Clark sliced into an array of building types, including, among other spaces, a wood-frame house in New Jersey and an iron foundry in Genoa, Italy. In cutting up buildings, usually slated for demolition, he managed to create disorienting walk-through sculptures that deftly fused conceptual art with earth art with performance art. And it was political art too. Matta-Clark was practicing at a moment of widespread urban disinvestment. Entire neighborhoods were wiped out in some places (usually the poorer ones) to make way for fancy new Brutalist and high-tech towers erected in the name of urban renewal. But should buildings get precedence over the people they displaced?

Matta-Clark studied architecture at Cornell University and was critical of many of the theories he studied. If his problems with the field weren’t made clear enough by his cuts, in 1976, Matta-Clark made one unmistakable gesture that would leave nothing to interpretation. Rather than participate in an exhibition at the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies in New York as planned, he instead shot out the school’s windows with a BB gun.

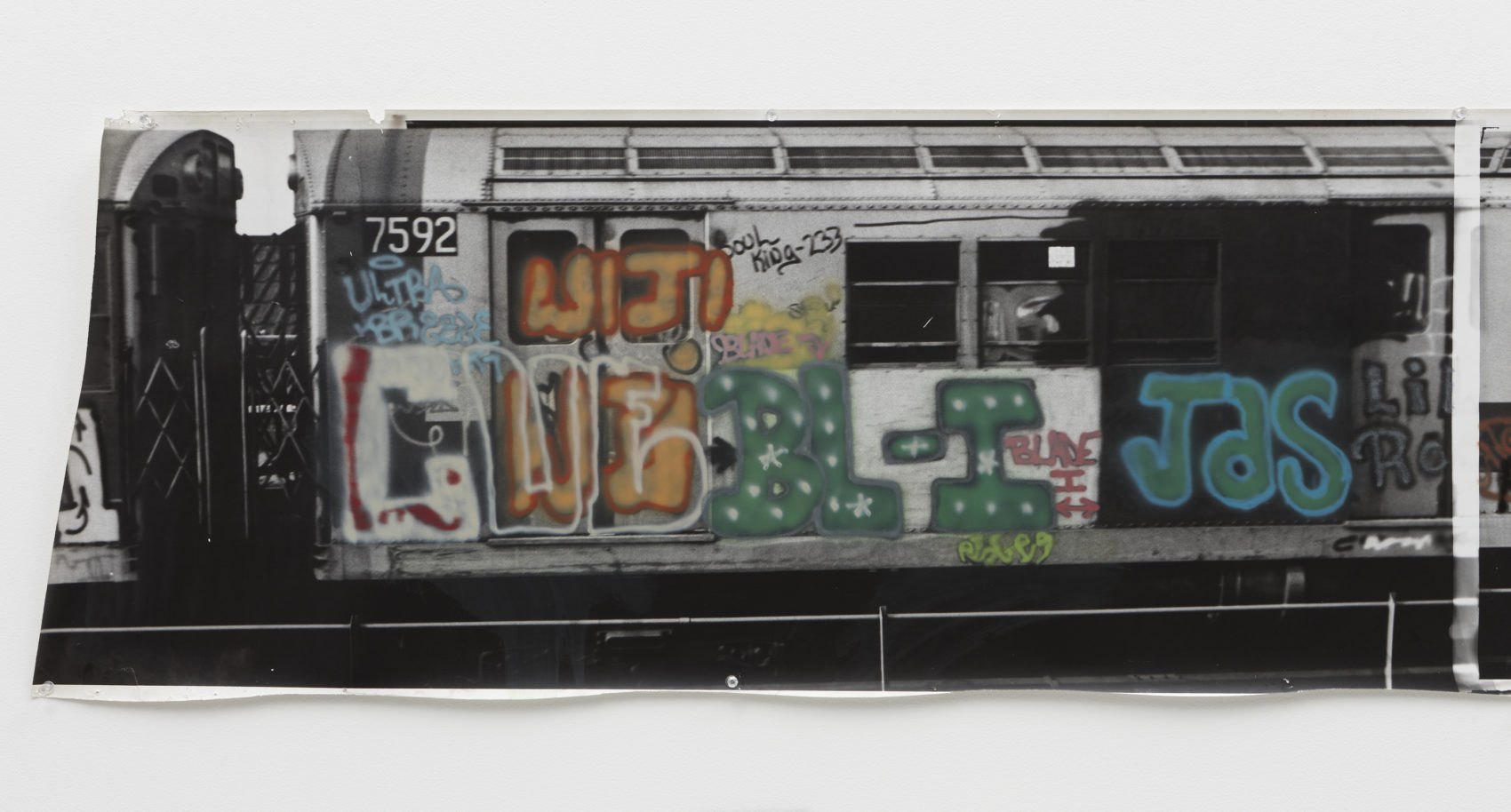

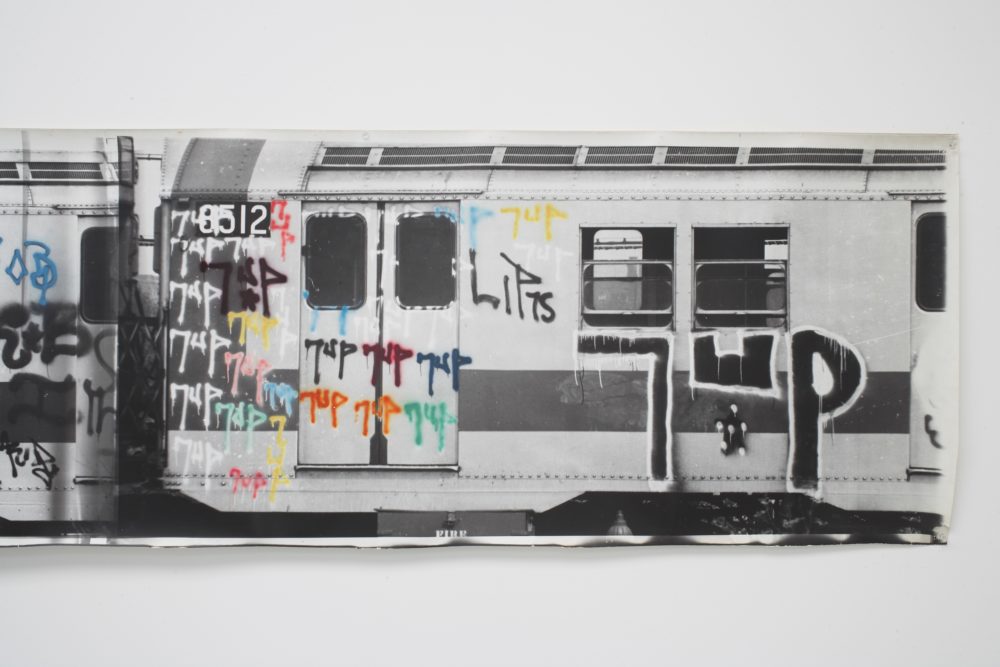

Such radical destruction certainly lent Matta-Clark a legendary James Dean, guerilla artist status. Clearly, he belonged to a generation dissatisfied with authority. But it only represents a part of what he was about. Son of the celebrated Chilean Surrealist painter Roberto Matta and American painter Anne Clark, Matta-Clark was concerned with building something too. A number of his projects were dedicated to community outreach, including developing a prototype shelter for the homeless made out of trash entitled “Garbage Wall,” a mobile public artwork called “Fresh Air Cart,” in which city dwellers were invited to suck in oxygen and nitrogen from a portable tank strapped to two wheelchairs, and a collaboration on a SoHo restaurant called “Food,” which functioned as an artist's cooperative, restaurant and performance space. He was also intensely interested in the bowels of the city, snapping photos of tunnels, sewers and catacombs, as well as graffiti-sprayed subway cars. For Matta-Clark, graffiti was the "people’s art."

Iconoclast that he was, it would turn out that Matta-Clark’s odd, visionary art would foreshadow trends in subsequent decades, including graffiti art, made famous in the ‘80s by artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenneth Scharf, as well as a community activist art, seen and now practiced in every corner of the art world — from the Guerrilla Girls to Justseeds to Theaster Gates.

“It's so pertinent to the time that we live in, in terms of there's a lot of activism with people trying to think of what's the way forward,” says Croquer. “And here you have somebody who comes at it from a very kind of new, and still today, unexplainable way.”

As radical and rebellious as Matta-Clark may have seemed, his temporary work has left an enduring legacy.

“He occupies a space as a visionary artist,” he adds. “The work is still unfolding and we're still learning from him and having to unpack a lot of these things, which ask the important questions about where we are today, about resourcefulness, about solutions that are made jointly and in a world that's so divided.”

According to Gloria Moure's 2006 "Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings," Matta-Clark described his legacy this way to a group of Italian workers: “What I do to buildings is what some do with languages and others with groups of people. I organize them in order to explain and defend the need for change.”

“Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect” is on view at the Rose Art Museum from Sept. 21 through Jan.5, 2020.