Advertisement

Landmark Or Eyesore? The Future Of Boston’s Hurley Building Is Uncertain

The future of a brutalist landmark in Boston is in doubt.

Last month, the Baker administration announced its intention to redevelop the site of the Charles F. Hurley Building, an imposing concrete structure near Government Center that houses a number of government agencies. Designed by the influential modernist architect Paul Rudolph, the Hurley Building is an exemplar of the architectural movement known as brutalism, at once stark and monumental, with massive concrete pillars and a looming brow.

In a development proposal released last month, the Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance, or DCAMM, described a building suffering from deteriorating conditions and poor design. The agency estimated that renovation would cost the state $200 million, and advocated instead for ground-leasing the site to a development partner, leading many to believe the building would likely be demolished and replaced.

As word of the Hurley’s precarious fate spread on social media, advocates picked up the cause. Now, preservationists hope that changing attitudes toward brutalist architecture could preserve the building.

The term "brutalism" was coined in the 1950s to describe an emerging style of modernist architecture, its name a reference to its practitioners' material of choice: raw concrete, or, in French, "béton brut." The harsh, geometric style proliferated in institutional buildings, its unfussy exteriors gracing the likes of schools, churches and housing projects the world over. Boston is home to a number of notable examples, including the Boston University School of Law tower, parts of the Christian Science Plaza and Boston City Hall, which, in 2008, was infamously named the ugliest building in the world by the (now defunct) website VirtualTourist. Brutalism fell out of favor in the 1980s; exposed concrete, it turned out, didn't age well, and those massive structures, intended to inspire a sense of civic pride, suddenly seemed oppressive, totalitarian.

Ten years ago, the potential demolition of a mid-century concrete specimen like the Hurley would have elicited little pushback in the public sphere — or perhaps even earned applause. But a revived interest in brutalism in the past several years means the Hurley has a fighting chance. Some attribute that to an appreciation for the honesty and integrity of the form, others to the permanence of such a concrete creation in an uncertain world. Brutalism's Instagrammable-ness doesn't hurt, either. “It's wonderful that there's been public interest and attention and concern about a potential loss of a building that's really of a style that has been underappreciated,” said Boston Preservation Alliance executive director Greg Galer. “I think we've turned a corner in that regard.”

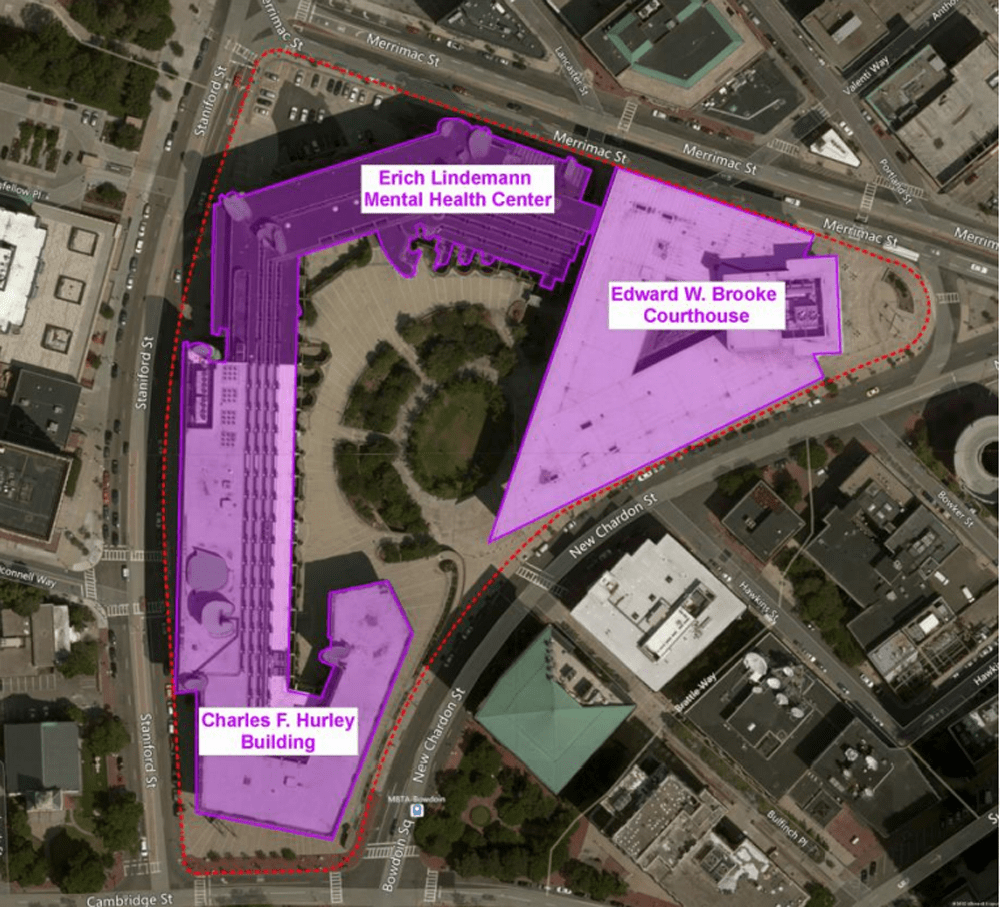

The Hurley Building is part of the Government Service Center complex, which was designed by Rudolph and completed in 1971. The original plan called for three buildings surrounding a plaza, but in the end only two buildings — the Hurley and the Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center — were completed, along with a portion of the plaza, while plans for a high-rise tower were scrapped.

In recent years, the Hurley Building has contended with both structural and image problems. A 2014 analysis of the Government Service Center undertaken by the Wentworth Institute of Technology and DCAMM described the complex as lacking “people friendliness,” with a difficult-to-navigate layout, poor climate control and uninviting concrete interior walls. In a press release sent in response to WBUR's inquiry, DCAMM cited many of the same issues. “The design and condition of the interior and exterior of the building mean there are limited opportunities for improvement through renovation, which is necessitating the complete redevelopment of this facility,” the agency wrote.

But preservationists were unanimous in their insistence that significant improvements to the interior could be achieved without destroying the essence of the building’s distinctive look. “The space isn’t bad,” said Chris Grimley, of the Boston design firm Over,Under, who toured the Hurley Building with representatives from DCAMM earlier this month. “A good creative team could reuse and adapt that building in ways that would act as a kind of beacon of how you transform these ... very monumental concrete buildings.”

Galer, who attended the same meeting with DCAMM, echoed the sentiment. “There's certainly many great examples of challenging mid-century modern buildings that have been modified to deal with some of the inherent challenges, maybe due to some design flaws from the beginning, and to the changing demands and needs for buildings, that have been very successful,” Galer said, pointing to renovations done to the Boston Public Library’s Johnson Building and the Boston University School of Law tower as successful examples. “There's a lot of possibilities here,” he added. “It's complicated, but it can be done.”

In fact, efforts at rehabilitating the Government Service Center complex have been undertaken in recent years. The large central plaza was closed for a decade due to its hazardous layout, which included a long drop-off between the edge of the ground-level plaza and the parking garage below. It reopened this past June. Now that the plaza is up to code, further activation of the vast open space is possible. “There's no programming there,” Galer said. “The opportunity to do something with this site, maybe with additional construction somewhere, and bring more life and people through the space, could really enhance it.”

DCAMM’s new redevelopment plan notably does not propose any changes to the Lindemann Mental Health Center. The Lindemann is widely regarded as the more significant architectural achievement, in part because because Rudolph was more heavily involved in its design and execution. Though he was the coordinating architect on the entire Government Service Center project, the firm Shepley Bulfinch Richardson & Abbott is credited with the design of the Hurley Building. Advocates for the Hurley's preservation worried that this fact could doom what they saw as a lesser, but still important, example of Rudolph’s singular aesthetic: soaring sculptural forms, dramatic interiors and rippling, bush-hammered concrete.

In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Rudolph was one of the most famous architects in the country. “You couldn't open a newspaper or magazine without seeing his pictures and his drawings everywhere,” said Kelvin Dickinson, president of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation. Born in Kentucky in 1918, Rudolph attended the Harvard Graduate School of Design and is most famous for his brutalist design of the Yale Art and Architecture Building. According to Dickinson, Rudolph was inspired by his first encounters with classical architecture on a trip to Europe early in his career. “He comes back from Europe and he says, ‘We need to create places like the plazas of Italy and Venice,’ where you've got buildings that stand out and you've got buildings that recede. And you've got these plazas that he thought Americans didn't have because we're so used to the grid plan,” Dickinson said.

The massive concrete buildings that Rudolph and others of his ilk created aren’t easy to love. But brutalism's admirers say there is beauty in these powerful structures, a kind of expressive severity. Galer pointed to Boston’s City Hall, which has been widely lauded by architects as a brutalist masterpiece, but is nevertheless a favorite target of public ire. “A lot of people look at City Hall and immediately have a problem with it, but if they were actually to walk inside, particularly the third floor lobby, and look up and around, there are some really incredible spaces and interplay of shadow and light and repeating patterns and a whole host of things that really make these buildings very sculptural, and very different than the glass towers that these were a response to,” Galer said.

Galer said that he was “cautiously optimistic” about the future of the Hurley Building after his meeting with DCAMM. “They were very clear that there is no preconceived notion about how this is going to go and that they're looking forward to a collaborative process with the Boston Preservation Alliance,” he said. Still, the agency has not publicly committed to preserving the building.

DCAMM's proposed redevelopment plan represents a potential windfall for the state. A development partner would shoulder the financial burden of the massive construction project and could provide significant rental income to the state, depending on the terms of the deal.

Before it can put out a request for proposals, DCAMM must file a project notification form with the Massachusetts Historical Commission and come to an agreement with the commission regarding the terms of development. The agency expects to begin looking for a a redevelopment partner next summer and begin construction in late 2022 or early 2023.

Preservationists vowed to keep the pressure up. Dickinson put it simply: “This building is bigger than Boston," he said.

This article was originally published on November 19, 2019.