Advertisement

Boston's Museum Of Fine Arts Goes All Out For Self-Portraits

“Every painting is a self-portrait,” the late Boston artist Ralph Hamilton used to say. But some paintings — and drawings and photographs — really are portraits of the artist who made them. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts is currently going all out for self-portraits. Three very compelling shows are running simultaneously, right next to one another or very nearby.

I’d advise starting with the biggest one “Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits” (through May 25) and ending with “Elsa Dorfman: Me and My Camera” (through June 21), partly because the Freud show is dark and disturbing and the Dorfman show is nothing if not a portrait of a chronic optimist. Your teeth might clench looking at the Freuds, but you are guaranteed to smile the moment you see Dorfman.

Lucian Freud, grandson of Sigmund Freud, was born in Berlin, but lived most of his life (1922-2011) in England. He made pictures of himself from the time he was a teenager till the end of his life. “Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits” is practically an autobiography. The first thing we see in the show is a flirtatious letter from a cocky youth to an older poet, Stephen Spender, who was in love with him. Young Freud’s crayon and watercolor portrait of himself takes up half the page, his handwriting circumnavigating the image.

Some of his most brilliant work begins in the 1940s — paintings in which he appears with strange symbolic birds or plants. He is now more evasive than when he was younger, suspicious, possibly angry or guilty. His eyes often turn aside or look down. Is he looking down his nose at us, his viewers? Perhaps it’s nothing more than the result of the way he painted his self-portraits, looking down at a large mirror resting on the floor.

His last portraits are ruthless images of a man in old age, the thick paint embodying his loose and decaying skin. The recent Hyman Bloom show at the MFA, another scary exhibit, would have made a fascinating comparison.

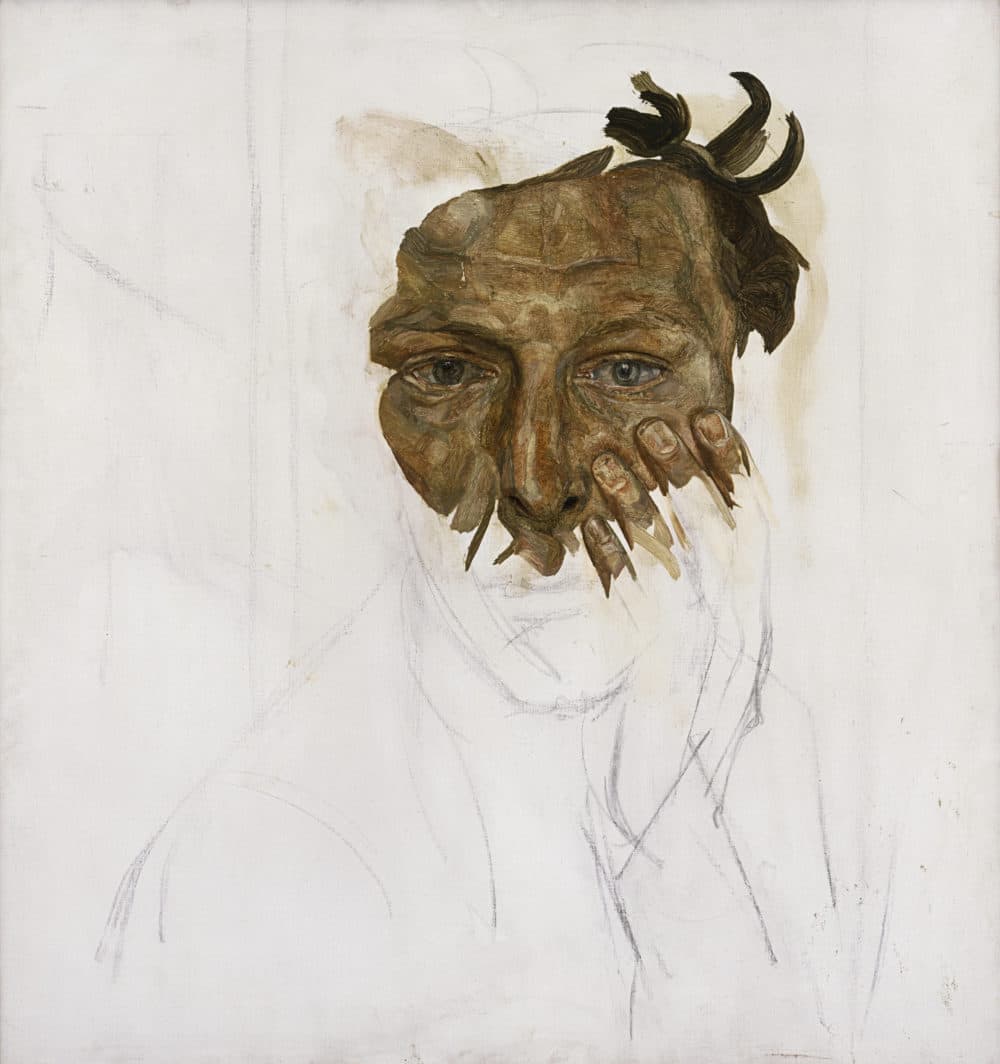

One of the most powerful features of Freud’s later paintings is that he left many of them incomplete (he hated the word “unfinished”). On a surface painted white, there is often a detailed, realistic portrait of his head, with the rest of the picture only a loose sketch of the rest of his body on the white surface. In “Self Portrait, about 1956,” he painted a detailed image of his eyes and nose and disheveled cobra-like hair, and the tips of his fingers touching his cheek, leaving the rest white. That white space seems to be eating away at his flesh, about to devour the rest of it. Even his painted fingertips seem to be clawing at his face — an image of extreme torment.

A painting from 1993 — 37 years later — is a full-length image of himself, nude. But here only his head and shoulders are painted in detail, in color, while the rest of his aging body is just a ghost, a sketch against the white background. His head seems a little too small for that disembodied body. Here the effect, unlike the 1956 picture, is more poignant, even heroic — an aged body trying to survive its own decrepitude.

The excellent catalogue, which includes an evocative essay by Freud’s longtime assistant and model, David Dawson (former Boston Globe art critic Sebastian Smee also has an essay), offers a timeline of self-portraits by great artists, including Rembrandt, Dürer (a still startling full frontal nude drawing), van Gogh and Schiele. But Freud’s late images of himself remind me most of the late self-portraits of Pierre Bonnard, whose whole career was based on glamorous and extroverted colors, but whose surprising late self-portraits are stark, intimate and heartbreaking self-scrutinies. Freud’s paintings aren’t exactly heartbreaking. “I wanted to shock and amaze,” he once said. And the shock value of his earlier, more ambiguous paintings remains in these late self-portraits in which he no longer sees himself as impenetrable.

Freud, Dawson tells us, actually destroyed as many of his self-portraits as he kept. Though they look like they were done in a single burst of energy, he actually worked very slowly. A painting could take him a year to finish. These seemingly “incomplete” paintings were deliberately incomplete, or he wouldn’t have decided to keep them.

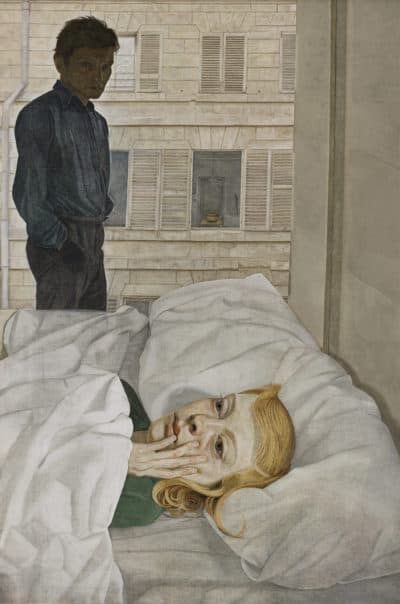

In Freud’s earlier paintings, the surface was very refined and glassy, shiny yet flat. They often suggest something secret, a mystery in — or behind — them. One chilling picture titled “Hotel Bedroom” (1954) depicts a shadowy Freud standing in front of a window. We can see the building across the street better than we can see him. Freud’s wife at the time, Caroline Blackwood (who would later marry Robert Lowell), lies in the bed, under a white sheet or blanket, facing away from him and toward the viewer, the elongated bony fingers of her left hand up against her cheek. Blackwood called this a cruel painting.

It’s certainly a little creepy, but haunting — an Edward Hopper image as if it were painted by a Surrealist. The brushstrokes are almost invisible on this slick surface. Later, he turned to a wider brush, thicker, more visible, more kinetic strokes.

One delightful aspect of this show, curated by the MFA’s Akili Tommasino, displays the way Freud played with the very idea of a self-portrait. In “Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening” (1967-1968), a nearly 4-foot-square painting of what seems like a giant snake plant, we glimpse Freud’s head and bare shoulders through the fronds, his hand cupped to his ear.

Another large painting, “Two Irishmen in W11” (1984-85), is a vivid character study of two slightly seedy men in suits and ties, one seated, the other standing behind him. (Someone at the press preview told me with great authority that these figures were Freud’s bookies.) We can see the neighborhood out the window. But we have to work a little to see why this painting was in a self-portrait show. There on the floor, under the window, leaning against the wall, are two tiny self-portraits.

Another painting is even sneakier. “Flora with Blue Toenails” (2000-01), is a painting of a nude model contorted on a bed. The artist is nowhere to be seen. But isn’t that the shadow of the painter on the bed?

Most of these paintings in this show are from private collections and have been rarely on public view. The catalogue includes photos of paintings that were in the London version of this exhibition, but not in Boston, among them several full-length nudes. Curator Tommasino told me he tried to get one of them for this show, but last-minute complications prevented it from traveling to Boston. It’s a pity. The bravado — and heroism — of these uninhibited nude self-studies is extremely important in Freud’s work, and the show suffers from this absence. That said, this is an impressive and memorable show.

And off to the side is also a study room — a replica of Lucian Freud’s studio, with a place on the wall for one of his actual palettes. There you can see a four-minute video, excerpted from a longer documentary on Freud, in which he says:

I want each picture that I’m working on to be the only picture I’m working on.

To go a bit further: the only picture I’ve ever worked on.

To go even a bit further: the only picture anyone has ever worked on.

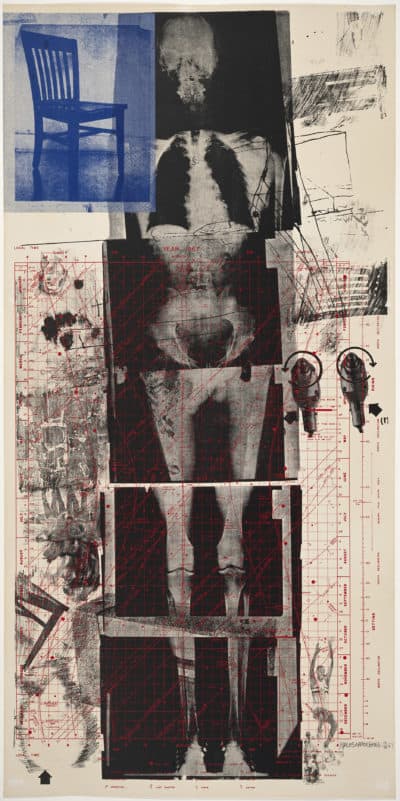

For more self-portraits, look for a small room labelled “Personal Space: Self-Portraits on Paper.” An array of images, curated by the MFA’s Patrick Murphy, meet the eye: drawings and prints and works in other media (including a small sculpture by Oskar Kokoschka — it’s cheating, but I’m not complaining) by some famous names. The most famous is probably Robert Rauschenberg’s 1967 “Booster,” a color lithograph and silkscreen running down the center of which is an X-ray of his own skeleton surrounded by totemic objects. Some of the artists deserve more recognition, like the late African American artist Allan Rohan Crite, represented here by a poignant self-portrait on the rundown corner of Dilworth and Northampton Streets in Boston’s South End. The most piercing image in this show is a double self-portrait by the late Michael Mazur he titled “Mother’s Boy ’41 and ‘89,” drypoint images of himself at 53 and himself at 6. The young and the adult Mazur stare out at the viewer with the same unflinching intensity. The child is father of the man.

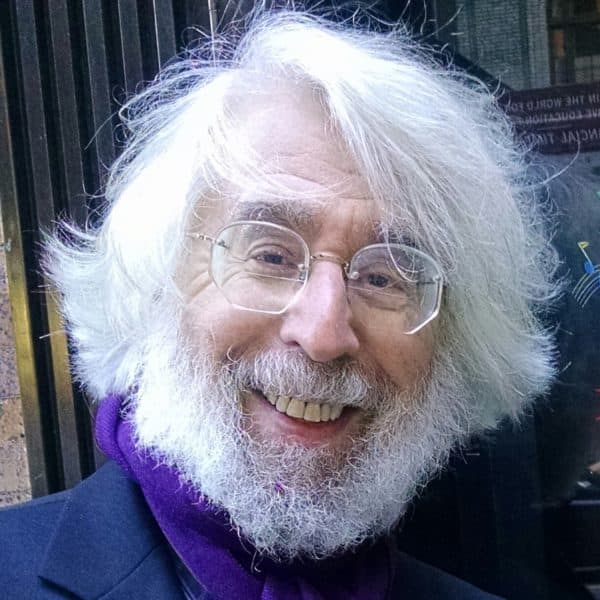

In the very next room, you’ll find a more immediately uplifting experience. “Elsa Dorman: Me and My Camera” is another autobiography in images from the time that Dorfman, in 1980, took her first photos with the giant polaroid camera she is famous for using. She’s taken so many photos of local denizens, we might forget the joyous and lovable photos she took of herself and her immediate family, which this beautifully curated show by the MFA’s Anne Havinga and James Leighton now remedies. If I had to pick a favorite — very hard to do — it might be Dorfman on her 54th birthday with her husband, lawyer Harvey Silverglate, and their son Isaac all wearing bright crimson sleepwear, with some black birthday balloons floating off to the side.

Dorfman is also famous for her friendships with poets, especially Allen Ginsberg. “Me, with Peter and Allen during their photo session, Isaac’s Amaryllis in bloom from studio light” (1980) celebrates the 25th anniversary of Ginsberg and his partner Peter Orlovsky.

The only sad photograph in the Dorfman show is a startling naked self-portrait, holding a pot of flowers in one hand and the camera’s cable-release in the other (1997). She and her quiet grief are both completely exposed. Her caption for the photo is “I’m sixty. Allen’s dead.”

“What I love about it,” Dorfman says about photography, in a clip from her friend Errol Morris’s loving film about her called “The B-Side,” is that a photograph is all artifice, an artifact — “It’s not real at all.” Snapping a picture at precisely the right moment is to her always “amazing — it’s like a gift!” The photographs, she says, are not about what she has elicited from her subjects, but what the camera “gets back” from them. “I am not interested in capturing your soul.” And yet her almost always smiling, generous sweet soul is precisely what all her self-portraits have captured.

At the MFA, “Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits” runs through May 25 and both “Elsa Dorfman: Me and My Camera” and “Personal Space: Self-Portraits on Paper” run through June 21.