Advertisement

Review

The Horrifying Beauty Of Hyman Bloom's Paintings

Walking through the impressive and disturbing show “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death” at the Museum of Fine Arts, I stopped in front of a painting called “Self-Portrait.” It’s a painful, even violent image of a body torn open to reveal its skeleton. It reminded me of the famous painting by Rembrandt at the Louvre, “Slaughtered Ox,” which depicts a carcass hanging by its rear legs, flayed and cut open. That painting has always seemed a metaphor for all inner life, making frighteningly visible what mere skin attempts to conceal. Hyman Bloom’s painting could be anyone’s self-portrait.

Then, in a nearby room, there’s Bloom’s “Slaughtered Animal,” which is an even more direct reference to that same Rembrandt. The great and tragic 17th-century Dutch artist never seems far from Bloom’s mind.

Bloom seems passionately to be trying to see what's both literally and metaphorically under the skin. Surrounding the “Self Portrait” are two large-scale drawings of … are these also skeletons? No, they’re misshapen, skeletal trees. MFA curator Erica Hirshler says she intentionally invites this confusion. She wants us to see a painter who wanted to get under the surface of whatever he was looking at, and that for him looking at almost anything inevitably becomes a kind of clinical examination.

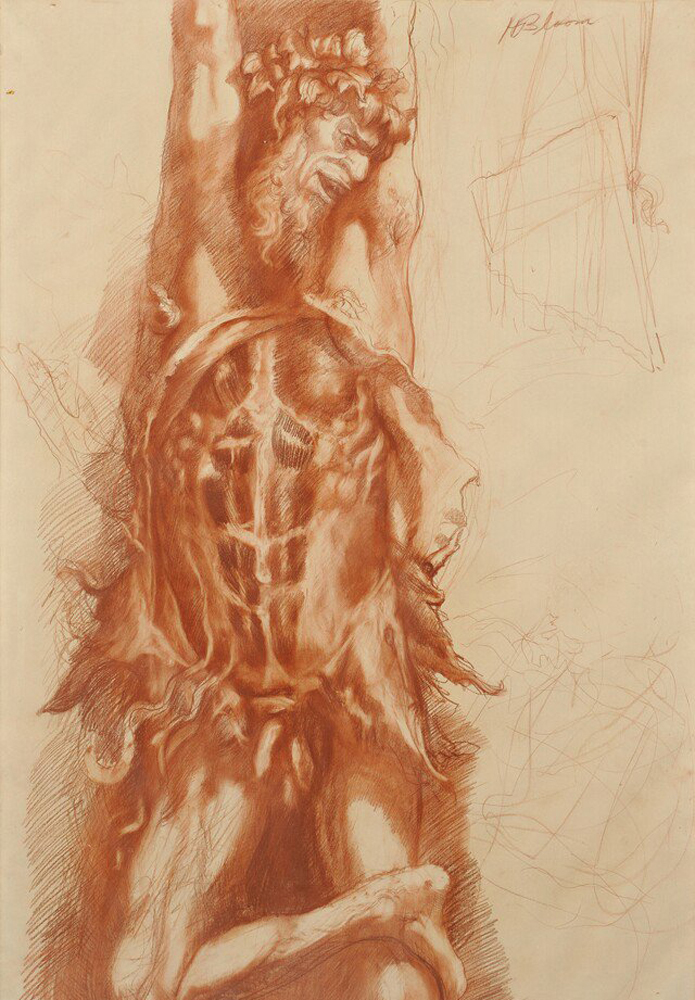

There are quite a number of cadavers in “Matters of Life and Death,” both male and female, human and animal. One male corpse is alive enough to have strikingly explicit genitalia (a painting banned from several exhibits). One of the central images in this show is Marsyas, the pan-piping satyr who challenges Apollo to a musical contest, which he inevitably loses. His penalty is to be skinned alive. And commanding its own wall, there is Bloom’s excruciating/stunning conte-crayon drawing of Marsyas — already flayed and with his guts exposed. One of the last and most devastating of the great Renaissance artist Titian’s paintings is “The Flaying of Marsyas.” Like Titian’s, this is a very dark image of the price the artist pays to create art.

Horrifying as some these images are, there’s also beauty in them: exuberant splashes of paint, vivid, often clashing colors — more vivid in the flesh, as it were, than in any reproduction. And this life-affirming technique, however queasy it might make us, carries over into almost every subject: gourds

a severed leg on a bench against a startling white background (which is rare in Bloom's work)

Christmas trees or a magnificent chandelier in a synagogue seen from below

paintings of a Jewish Bride (another Rembrandt allusion), one darkly supine, as if she were asleep.

She’s almost in the same position as Bloom’s “Skeleton”:

There are many Judaic images in this exhibit — one of the four Bloom paintings hanging elsewhere at the MFA depicts an elderly Jew holding a Torah. And each one has an almost surreal mixture of earthiness and spirituality.

“Matters of Life and Death” also includes a number of Bloom’s drawings, some of which are extraordinarily delicate. His images of old people are particularly touching.

Bloom was one of the leading artists in Boston in the 1940s and ‘50s, the center of a group of Eastern European emigres who earlier in the century came to the United States to flee pogroms, or escape Nazi persecution. He was born in 1913 in a Latvian village now part of Lithuania and died in Nashua, New Hampshire, in 2009. In the 1940s and ‘50s, his work was widely exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Venice Biennale, the Whitney, at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, and elsewhere. The MFA owns important paintings by him, yet it hasn’t — until now — presented a major solo show.

Advertisement

I asked one of Bloom’s Boston friends about him, Harvard clinical and forensic psychiatrist Harold Bursztajn, who is the lender of the painfully unsettling Marsyas drawing. “Hyman Bloom was a very private man,” he told me. “He all too often felt disappointed in his own body, in himself, and suffered deep grief in his life. At the same time there was a deep wit and a sense of profound irony and kindness that Hyman shared with a few."

Dr. Bursztajn recalled his first meeting with Bloom ("He quickly learned my family history, and shared some of his own"). Their ensuing conversations, he said, ranged from such topics as "the nature of time, the unconscious, American slavery and racism, and how can art be possible, or perhaps necessary, post the Shoah."

He told me that Bloom “openly revered” Turner’s wildly expressionistic “The Slave Ship” at the MFA. In the American wing, Bloom’s “Seascape II,” with its fish-heads crammed together (Yeats’ “mackerel crowded sea”?), now hangs on the opposite side of a doorway from Turner’s masterpiece. “Rather like Rembrandt's response to grief and Turner's to slavery,” Dr. Bursztajn continued, “he beautifully reminds us as a social critic that we are all in the same boat. While Bloom's one foot is in Yenner Welt [the other world] the other is firmly in the woods of this one.”

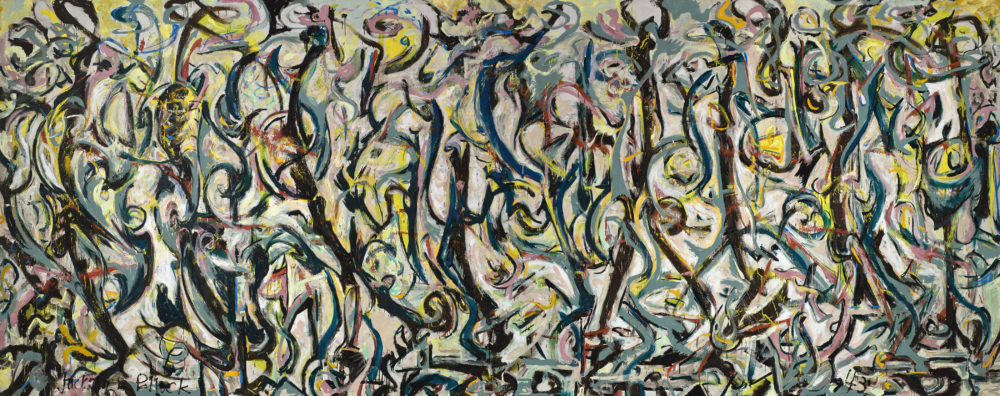

How to define what kind of painter Bloom was — figurative? quasi-abstract? expressionist? symbolist? — still arouses controversy. Some clarification is provided by the startling juxtaposition of the Blooms with the adjacent exhibit: “Mural: Jackson Pollock/Katherina Grosse” (in the MFA’s Rabb Gallery, through Feb. 23).

Pollock’s largest canvas is a 20-by-8-foot painting called “Mural,” commissioned in 1943 by the collector Peggy Guggenheim for the hallway of her Manhattan townhouse and currently on loan to the MFA. It is perhaps Pollock’s most important painting before his revolutionary drip paintings (the MFA has one smaller example of these in its Art of the Americas wing). It’s a huge curvilinear abstraction with repeated, almost dancing biomorphic figures, undeniably exciting if not exactly ravishing. Here it is thoughtfully hung on a recessed wall that suggests its original installation. But the real joy of seeing it in person is being able to inspect its dazzling details.

Sharing the space, and taking up a great deal more of it, is an untitled (or titled “Untitled”) free-hanging canvas 48 feet wide by 16 feet high by the German artist Katherina Grosse commissioned by the MFA to share the space with and comment on the Pollock — a Technicolor post-Pollock phantasmagoria, with different swirls of paint on each side. It’s hung perpendicular to Pollock’s “Mural.” The whole installation seems vast, serious and monumental, yet it’s also fun to walk around the Grosse and come at the Pollock from different angles.

Bloom was working at the same time as Pollock, without nearly the celebrity that Pollock achieved. Bloom was decidedly not an abstract painter, and didn’t want to be, though some of his images are so densely painted they are hard to read as anything but abstractions. I've been told that as far as Bloom was concerned, what most of us regard as Pollock's breathtaking masterpieces lacked intellectual content.

Congratulations to Erica Hirshler for presenting a show more daring and less academic than we might have expected, something more to do with images and ideas, “matters of life and death,” than, say, a chronological retrospective. The best argument for considering Hyman Bloom an important painter is in those ideas and the way his work ruthlessly embodied them, refusing to charm, and even risking the dismay of his viewers.

"Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death" is at the MFA's Foster Gallery through Feb. 23.