Advertisement

Sculptor Dennis Svoronos Uses Technology To Explore Representation In Exhibition 'Proof Of Life'

So much of life is lived digitally nowadays. Our relationships, friendships, and jobs have moved online, compacted into these small rectangles: Zoom calls, profile pictures, phone screens, and glowing computer monitors. But there’s always more that lays outside the frame — what’s seen online isn’t ever the full picture.

Months before the pandemic made our already-online lives even more digital, Dennis Svoronos — sculptor, tinkerer and sort-of-scientist — began exploring the technologies we use every day and the ways they represent (and sometimes misrepresent) the self and the culture. Thriving somewhere between fine art, anthropology and engineering, Svoronos’ multidisciplinary work questions who we are, who we say we are and how we represent ourselves through the unusual mediums of tech and social media.

“Greeks and Romans used marble and bronze to talk about the body, culture, beliefs,” he explained, pacing the floor of Boston Sculptors Gallery, where his exhibition “Proof of Life” is now on view. “I’m doing the same thing, I’m just using iPhones and Twitter, computers and brain scanners. It’s the bronze of the 21st century.”

Svoronos’ fascination with the veracity of data and technology has roots in his 2009 brain cancer diagnosis, which he’s still being treated for. “I’ve had EEGs in hospitals for years,” he says. “Other people get to study me in a way I don’t get to study me, until now. I could be physically looking at the white mass of my brain in an MRI but that feels so divorced from me.” Despite being subject to dozens of brain scans, Svoronos feels alienated from the clinical images ordered by his oncologists. They’re tools that capture one aspect of his life — his brain — but they fail to reflect his multiplicities, his wholeness.

These impersonal, monolithic images prompted Svoronos to question: What can technology teach us about ourselves, what must it leave out, and what can’t it capture? Raised in a family of carpenters and construction workers who taught him plumbing and drywalling, Dennis took to making to answer his questions. His art practice evolved to problem solving and experimentation through the physical act of taking apart and rebuilding electronics. An inquisitive intellect with a buoyant sense of humor, Svoronos began to play with old phone chargers, toys and iPhone cameras to see how he could manipulate them to create new meaning.

Three such creations were “Brain Data Storage Cap,” which records and stores brain activity for later interpretation; “Melody Making Headpiece,” a wearable sculpture that responds to brain waves and produces music notes to correspond with one’s thoughts; and “Sheet Music Generating Helmet,” which translates the wearer’s subconscious delta waves into sheet music for cello. The high-tech self-portraits created by Svoronos’ machines stand in colorful opposition to the clinical scans produced by his doctors. His devices produce music and art, translating his brain activity into creative rather than diagnostic material. The resulting artworks, too, are scans of his brain, albeit designed to expose a different kind of truth.

Svoronos sees social media as another fallible tool, much like the EEG scans requested by his doctors: An instrument to describe an aspect of a person, not a holistic representation of one’s entire life. Things tend to be flattened on the internet, tinted with rose-colored glasses, turned into half-truths and full-blown lies. An Instagram grid may reflect one’s smile and their love of adventure, but it can rarely capture the quirks that make a person stand out, their emotional depth, or their love for those around them.

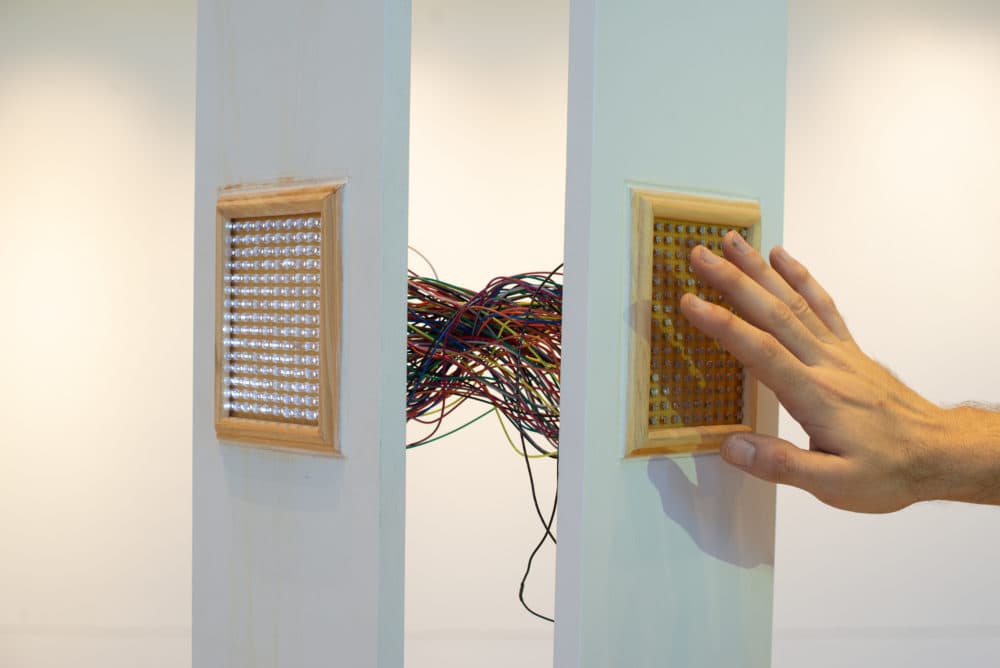

In “Hemispheric Communication,” another high-tech interactive piece, two electronic panels sit side-by-side. Viewers can wave a hand in front of one, and see it reflected — dimmer, mirrored — in the other. Although the images resemble one another, something is notably lost, altered in translation. An apt metaphor for the “real” self versus the self we live on social media. Svoronos sees the digital self as a “shadow” — a version of the “real” self that loses some of its depth in its new iteration — much like his own brain scans.

Svoronos’ experience looking at his brain scans mirrors a feeling experienced by many during quarantine: A discomfort, almost a dissociation, from the digital self you see reflected on the screen. Like you don’t recognize your image in what you see, or don’t want to. Whether it’s being distracted by your own video image during a work meeting over Zoom, or the result of an hour spent searching for the best room in your house to video chat, or the uptick in time spent scrolling on Instagram that causes a person to compare themselves to others, it’s important to unplug from devoted obsession over one’s online image.

Our digital lives are vital right now, but they’re not everything. There is always more than meets the screen.

“Dennis Svoronos: Proof of Life” is on view at Boston Sculptors Gallery through Sept. 20.