Advertisement

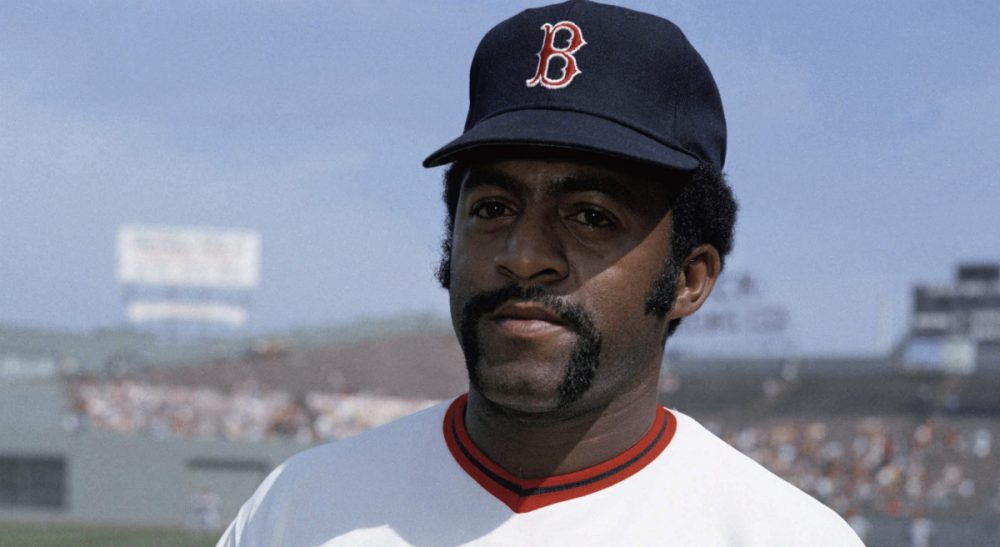

Luis Tiant Deserves A Place In Baseball's Hall Of Fame

“Never make predictions, especially about the future.”

These pearls of wisdom came from the lips of the late, great baseball manager Casey Stengel, a seven-time World Series champion with the New York Yankees.

While I would normally agree with the logic of “The Old Perfessor,” I nevertheless think an exception can be made when discussing the chances of former Red Sox pitching star Luis Tiant earning enshrinement to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, on Dec. 8.

“El Tiante,” as he was affectionately known to Boston fans at the height of his fame in the 1970s, is one of 10 names under consideration by the Golden Era Committee, a special HOF group of former players, team executives and writers set up to review the worthiness of candidates “whose greatest contributions to the game were realized from the 1947-1972 era.”

He had 'one of the most tenacious, killer instincts in the game,'

Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee

While Tiant faces stiff competition from the likes of three-time Minnesota Twins batting champion Tony Oliva, who batted .304 during a distinguished 15-year big league career, I think Tiant will ultimately capture the necessary 75 percent of the 16-member committee’s vote to prevail.

Why? The simplest answer is that Tiant has earned it. His impressive 229 career victories, 2,416 strikeouts and .571 winning percentage aside, he was the guy you most wanted on the mound when you absolutely, positively had to win a big game. Against Cincinnati’s vaunted “Big Red Machine” in the 1975 World Series, Tiant was at his optimal best, throwing complete game victories in Games 1 and 4 while captivating a national sports audience with his unique pitching motion. “He had the most bizarre windup I’ve ever seen,” wrote Hall of Fame teammate Carl Yastrzemski in his autobiography, “corkscrewing his body around so that that he was looking at second base almost the whole time and then suddenly, out of nowhere, delivering one of a dozen different pitches he had.”

That “bizarre windup” came from necessity. A feared fireballer when he first came to the majors with the Cleveland Indians in 1964, Tiant hurt his shoulder a few seasons later and lost his A-plus fastball. No matter. He learned to get hitters out by using his guile. “I learned you cannot win with a fastball alone,” Tiant admitted to Lew Friedman in his 2013 book, "The 50 Greatest Players in Boston Red Sox History." “You must always keep the batter off-balance. You must keep the ball low, keep it moving, keep it around the plate, in and out, up and down. You must always work.”

A surfeit of guts also came in handy. He had “one of the most tenacious, killer instincts in the game,” fellow Sox pitcher Bill Lee told the author Peter Golenbock in his book “Fenway.” “That’s what made him a great pitcher. He never gave in to the hitters. He knew when to trick hitters. He knew when he had a guy on the ropes, to bury him. Come the seventh, eighth, and ninth innings, you’d yawn and go back to sleep. Tiant closed them down.”

Sox General Manager Dick O’Connell signed Tiant in 1971 after the rest of baseball had virtually given up on him. The move turned out to be an outright steal. Tiant went on to win 15 games the following season while taking home Comeback Player of the Year honors and elevating Boston to pennant contention status. All told, he would post a sparkling 121-81 record for the Sox, in addition to being a 20-game winner thrice over.

Heroes deserve plaques in Cooperstown.

A native of Cuba, he was no stranger to adversity off the field, either. When brutal communist dictator Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, Tiant found himself exiled and cut off from his family. Not until 1975 would he see his mother and father again. And this was only because Castro, a huge baseball fan, granted them special permission to leave his island nation and live with their famous son. It was an emotional reunion. “As soon as I saw my father step off that plane, I put my hands over my eyes and cried,” the notoriously cool Tiant said at the time. “I wasn’t going to do that, but I couldn’t help it.”

I remember first setting my eyes on Tiant in 1977, when my beloved late father took me to a sizzling hot mid-summer game at Fenway Park against the Indians. The final score eludes me, but Tiant dominated with a series of head gyrations and off-speed pitches that left the Tribe batters baffled, if not thoroughly humiliated. At one point, he even loaded up the baseball with resin, and, when he threw it to the plate, you could see the powder literally fly off, much to my then rebellious teenage delight. It was the 1970s, after all, and it was the norm to bend a few rules — at least that’s how many of my contemporaries saw it during this time of pet rocks, platform shoes and roller disco.

Tiant was my hero, and even though he unceremoniously left the Sox after the 1978 season to wind up the majority of his later career in pinstripes with the hated Yankees, he still remains so.

Heroes deserve plaques in Cooperstown.