Advertisement

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's Remorse Changes The Story, If We Let It

I’m afraid we’re not going to tell the right story about the Boston Marathon bomber.

Just before the beginning of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s trial in early 2015, I argued in The Humanist for compassion toward the perpetrator. I expected a lot of backlash from readers who feel that demonization is the only appropriate response to terrorists.

Tsarnaev’s crimes can’t be undone, but remorse, that twist in events, could change the course of his story.

Much to my surprise, the critical feedback I received came from the opposite end, centered on my final words: “I think Dzhokhar deserves compassion. I also think he deserves to be locked up for life, filled with remorse.” One responder explained to me his interpretation of the etymology of “remorse”: consuming oneself. Is it compassionate to wish the young man a long life spent consuming himself?

No, that’s not what I wanted. The cyclical nature of such a fate is futile; Tsarnaev's story would go no further. I realized that I have a notion of constructive remorse — a feeling that can inspire one toward efforts to undo the harm done if possible and, if not, then to work against the repetition of such harms. Tsarnaev’s crimes can’t be undone, but remorse, that twist in events, could change the course of his story.

I don’t think we should underestimate the potential power of remorse in this situation. Once a "normal" and affable teenager, Tsarnaev, at the age of 19, murdered and maimed people. He was intoxicated by abstract and lofty justifications, like so many perpetrators of terror. If Tsarnaev feels remorse — if his ideological justifications collapse when confronted with the concrete results of his actions — this could be a real awakening for other young radicals flirting with the same notions that motivate some to claim innocent lives.

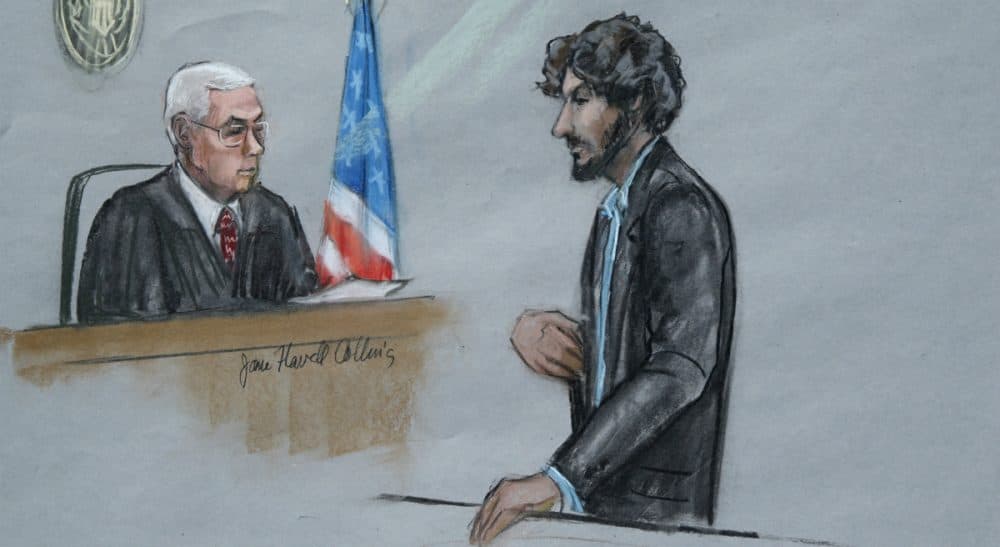

My hope was fulfilled on Wednesday; before his sentencing, Tsarnaev addressed the court:

"I would like to now apologize to victims and survivors. Immediately after the bombing that I am guilty of, I learned of some of the victims, their names, their faces, their ages. If there is any lingering doubt, I did it, along with my brother. I am sorry for the lives I have taken, for the suffering I have caused, and for the terrible damage I have done."

Tsarnaev then prayed for everyone present — for mercy, healing and relief.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev feels remorse. He can now serve as a cautionary example to others: The resolve of ideology dissolves in the face of the concrete harm it attempts to legitimate.

But Judge George O’Toole’s final words to Tsarnaev, before he issued the sentence of death by lethal injection, were not words that leave room for a new story:

“When people remember you, they will remember only the evil you have done," O'Toole said. "No one will remember that your teachers were fond of you, that you were funny, a good athlete. What will be remembered is that you murdered and maimed innocent people.”

O’Toole’s words were, of themselves, a kind of death sentence on the young man’s story. In condemning the criminal to his past, O'Toole left no room for constructive remorse — only the man in his cell, consuming himself, waiting to die. And, by condemning him only to the part of his past that is deplorable, O’Toole suggests we'll forget that the young man was once good. This amounts to a dismissal of the powerfully corrupting nature of fundamentalist ideology, which we can’t hope to resist if we don’t acknowledge.

I'll remember Tsarnaev’s pre-terror goodness and his post-terror remorse.

But we don’t have to tell the judge’s story. I'll remember Tsarnaev’s pre-terror goodness and his post-terror remorse. I hope that he won't accept the judge’s verdict on the sum of his life. I hope Dzhokhar Tsarnaev will make an effort to put the cautionary power of his remorse to use, aiming it at would-be fundamentalists. And I hope others will remember the full story: his corruption by fanaticism, the surety with which it drove him to inhumanity, and the return of humanity once he was confronted with the names and faces of the fellow human beings he murdered and maimed.

No story we ever tell could undo the harm that has been done. But if there is the slightest chance that telling the full story could sow a seed of doubt in young minds under the sway of fanatical, murderous logic, I don’t think it’s responsible to condemn Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to his heinous past.