Advertisement

Commentary

The Fleeting Hope And Wonder Of Man On The Moon

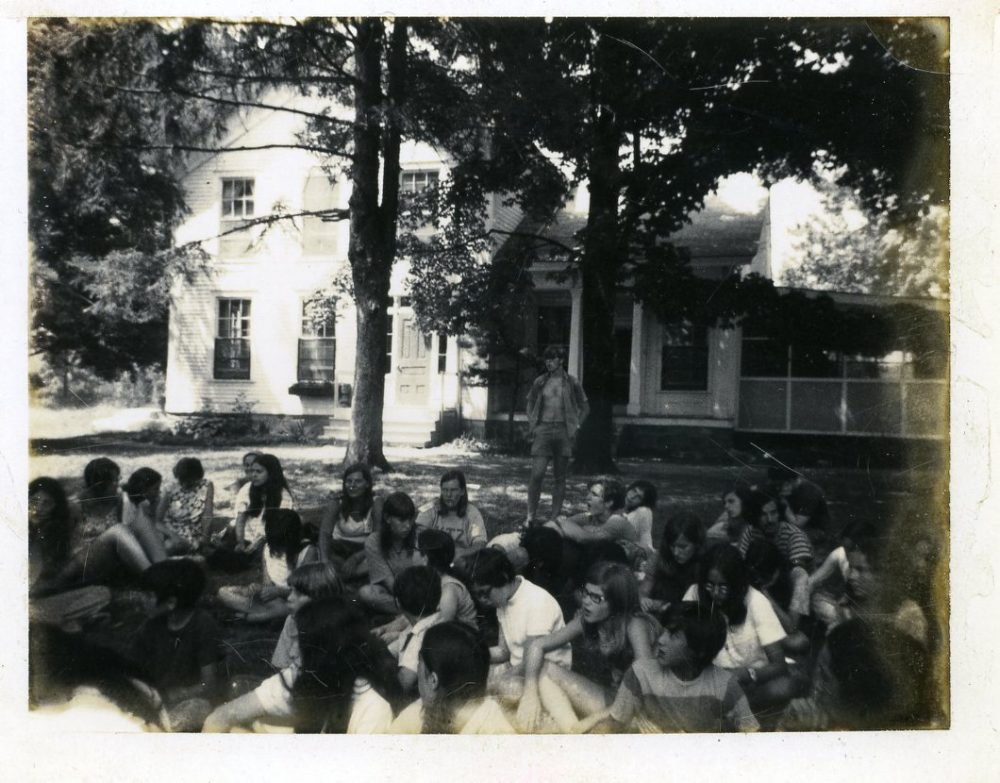

On July 20, 1969 — a hazy Sunday night — I sat on the ground with a hundred or so campers and fellow counselors at Circle Pines Center in Delton, Michigan, outside the farmhouse that doubled as dining hall. Accompanied by bursts of excited chatter, we peered at three small black-and-white TVs, that had been borrowed from neighboring families and carefully placed atop stacks of crates.

Since 1940, Circle Pines had served as a sort of summer school for vacationing adults — teachers, labor organizers and social workers with low budgets and high ideals. They went there to learn how to create and sustain economic cooperatives, including stores and housing complexes and day care centers in which people pooled dollars and labor to serve all participating members.

By the 1960s, when I first came there as a 15-year-old, it had become primarily a children’s summer camp. But its ethos had changed little. It was still a magnet for anti-war and civil rights activists, who were now joined by organic farming and natural foods advocates. They created a haven, however temporary, for themselves and their kids.

Staughton Lynd, a then-famous historian and anti-war activist, was a frequent weekend visitor to Circle Pines. He’d stand in the lake — the water never higher than his pale, concave chest — and schmooze with my friend Margie’s father, Tom, as if they were sharing Sunday brunch at the deli. Tom had been a brilliant physicist in his youth, one of several recruited to work on the Manhattan Project. But after the fruits of his labor decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he plummeted into a paralyzing depression. When he finally emerged from it, he went to work as a math teacher and chess coach at an inner city school in Chicago. Then, we thought of him as a sweet man, albeit a spacey one. Now, I recognize how broken he was by the consequences of his own actions.

Staughton and Tom and the rest were our teachers and our foils. As teenagers who had just crossed the threshold from camper to counselors — and thus from children to self-important young adults — we liked them, tolerated them, and of course, patronized them.

My generation was going to save the earth that theirs had despoiled with napalm and atomic weapons.

On that historic night in 1969 we’d been sitting on the lawn watching the tiny televisions for a couple of hours in mounting suspense. Though we knew enough to anticipate the communications blackout that would ensue when the space capsule was on the far side of the moon, those 32 minutes of radio silence were still nerve-wracking.

... the moon landing was like the moon itself, raising a tide of joy, advancing a labor that birthed a sense of wonder.

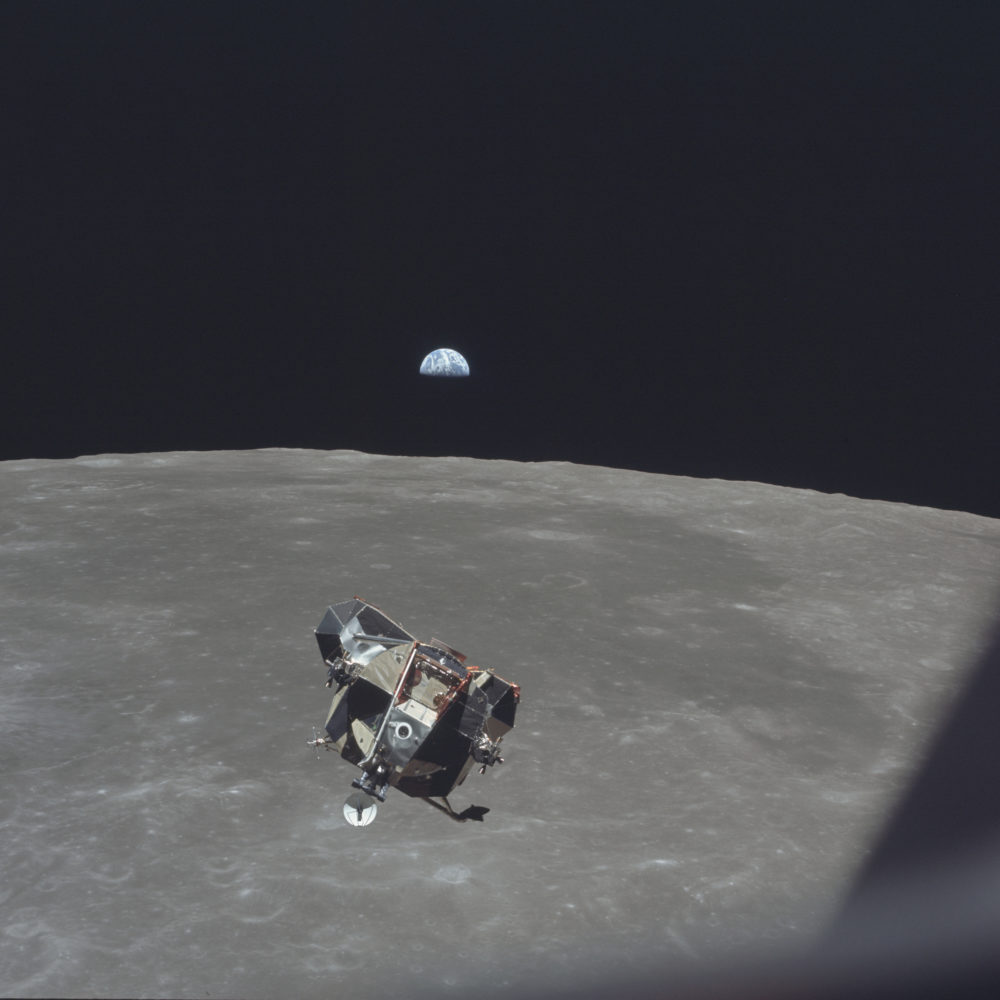

We cheered when it ended, and held our breath as we watched the lunar lander descend like a boxy spider. When Neil Armstrong eventually emerged from its small hatch and began climbing down the ladder to the moon’s ashy surface, we grabbed the hands of whoever was sitting next to us on the damp grass. And when he hopped down off the bottom rung and made his scripted declaration, we cheered and instantly looked upward at the pale and fuzzy moon, our jaws slack, our mouths open to the night air.

For one fleeting moment, the moon landing was like the moon itself, raising a tide of joy, advancing a labor that birthed a sense of wonder.

But since then I’ve wondered if televised marvels, events meant to make our hopes and senses thrum, have had the opposite effect.

After all, my cocky friends and I — our generational cohort — blew it. We did too little too late to save the planet we claimed to love. We lost interest in that bleak, black-and-white moon, and grew complacent about the green and blue, cloud-kissed planet that it orbited. We forgot what Tom and his shattered life had taught us.

Advertisement

On that distant night, when Neil Armstrong set foot in the moondust (which we now know smelled like spent gunpowder), we instinctively looked away from the television screens, trying to see him and Buzz Aldrin standing on the moon with our own eyes, unmediated.

It sounds foolish now, but what we saw on the small wavy screen — the astronauts looking like plastic action figures in their crinkly white jumpsuits and helmets the size of diving bells, the moon’s surface appearing a rutted, dusty abandoned lot — had nothing to do with what we saw in the sky, when we lifted our heads and looked upward. The video image defied our senses, and the dithery grayness of the moon’s surface on a television screen somehow trivialized the sight.

Not forever, of course. Blood moons, harvest moons, super moons, the sheer enormous emptiness of that luminous orb when viewed through a telescope: all of these spectacles still cause quickening and joy.

But what moves me now is the fleeting but profound community people felt that night, across generations, time zones and countries. What grieves me now is the repeated lesson of how difficult that is to sustain.

This segment aired on July 18, 2019.