Advertisement

Commentary

A Girls’ Weekend In Seneca Falls, The Birthplace Of The Women’s Suffrage Movement

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which granted women in the United States the right to vote.

Women voters, in raw numbers, have exceeded their male counterparts in every presidential election since 1964. With primary season now officially underway, women may indeed prove to be the key ingredient to a successful presidential bid.

I’ll admit that I have largely lost my stomach for today’s brand of politics. Respectful and truthful dialogue between those of differing views seems all but impossible these days. But despite this toxicity, I have never lost my interest in elections. When it comes to voting, I have a perfect attendance record.

I have cast my vote in all sorts of places, including school cafeterias, town halls and on one occasion, in the men’s bathroom of a nearby city park (the designated location for Democrats that November). No matter the scenery, I have always treasured the ability to pull the lever for my candidate of choice, an emotion I first recognized after witnessing a simple handshake.

Let us prove the most powerful four-letter word in the English language is V-O-T-E.

In the late 1980’s I moved to Rochester, New York, then known as a stopover on the way to Niagara Falls, a place of prolific snowfall and home to what the locals call the “garbage plate,” a collection of grease-laden food best eaten late at night, preferably after a long night out on the town.

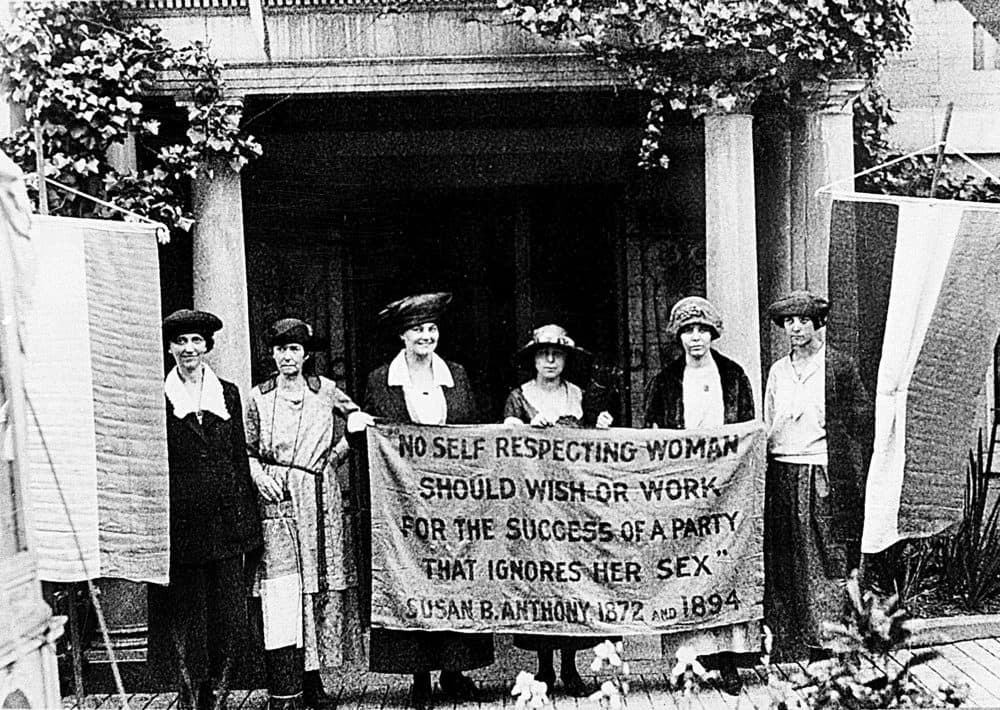

One weekend, looking for something more cerebral to do, I took a road trip with my best friend. Our destination was Seneca Falls, the location of the first women’s rights convention (held in 1848) as well as the National Women’s Hall of Fame (established in 1969). I had gotten the idea after stumbling across the gravesite of Susan B. Anthony, buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, just around the corner from my new home. Seneca Falls, ground zero of gender politics, seemed like the perfect fit for our girls’ weekend.

We made our way to the Women’s Rights National Historical Park, established just a few years prior to our visit. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home was on the premise, along with the M’Clintock House, the Wesleyan Chapel and a bustling visitor center. I was eager to see what Stanton had nicknamed “the center of the rebellion,” making her home the first stop on our tour.

After passing through Stanton’s front door, I noticed a small sculpture tucked away in a darkened corner. As I got closer I saw it was a plaster mold of two hands, locked together in a handshake. The top hand was wide and square, its small sturdy fingers unadorned. The other hand was long and lean, so long that the bony fingers stretched all the way underneath the other’s palm before appearing on the other side.

The hands were of Stanton and Anthony. A political power couple cast in plaster.

Scratched into the mold was November 12, 1895 — that was the evening both women were celebrating Stanton’s 80th birthday at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. As Anthony’s diary documented, the form was actually cast the following day, by sculptor Meb Culbertson.

For whatever reason, I found this plain rendering powerful, mesmerizing even. Perhaps it was because the sculpture mimicked my own hand and that of my own best friend so closely. Mine the pudgy Stanton version; hers of the slender Anthony variety. Perhaps it was the opportunity to examine the two women in such an intimate way, every wrinkle, every callous laid bare. All these years later, those plaster hands are what I remember most vividly about my visit to Seneca Falls. Theirs is the image that stuck.

As election season is once again upon us, our political system feels as if it’s teetering on the edge of catastrophe. And then, the image of those hands returns to me, reminding me of the power of friendship and solidarity, especially when shared between women.

One hundred and twenty-five years have passed since Stanton and Anthony locked hands on that November night in 1895. Both would die before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The ability to vote was their dream, their work, and their legacy, but never their right.

I owe a great deal to Stanton and Anthony, for theirs were the hands that pried open the doors of the voting booth for me. Let their example be a clarion call, particularly in this election where the voice of women needs so desperately to be heard.

Let us prove the most powerful four-letter word in the English language is V-O-T-E.