Advertisement

Commentary

Are Teachers The New Essential Frontline Workers?

I’ve always watched zombie apocalypse movies assuming I’d be among the first to go. I’m not a natural leader. I don’t know how to wield an ax. But it’s the constant not knowing that would do me in. What’s in the woods? What’s around the corner? Max Brooks wrote an entire book about surviving this kind of unknown. I avoided it.

Then my ER doctor husband went to live on a boat for 10 weeks while we quarantined at home at the apex of the pandemic in the northeast. I’ve had practice at moving through the duality of panic and comfort.

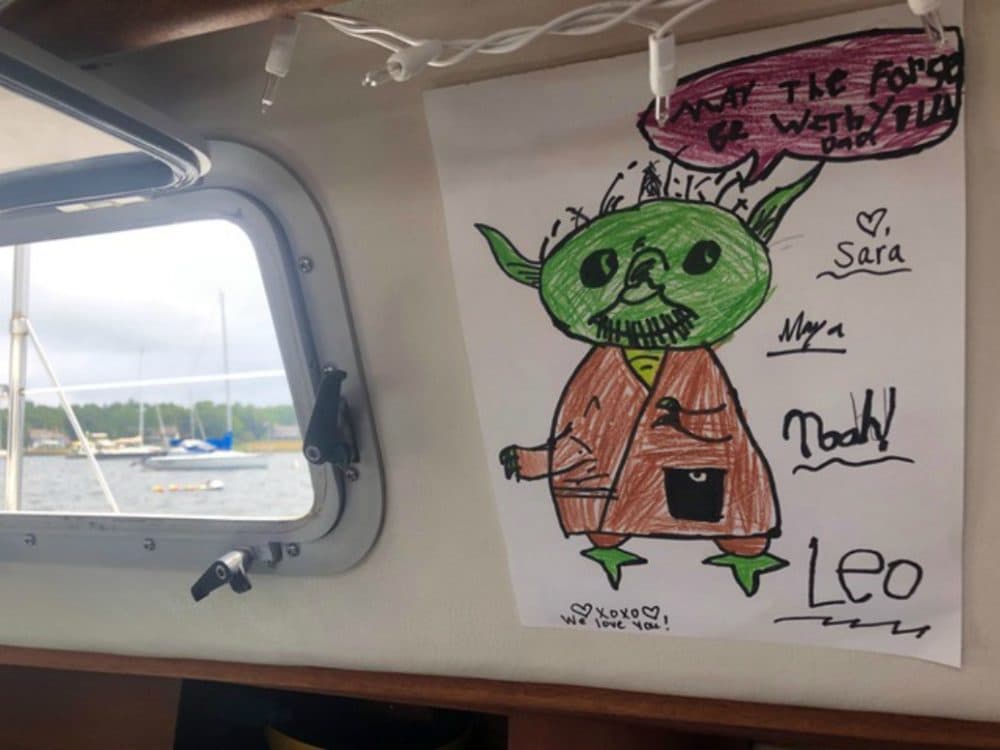

Last weekend I watched my kids swim from the boat my husband quarantined on. The picture my son drew of Yoda saying “May the Force be with You,” that we all signed when he left home, still hangs in the cabin. My husband’s emergency department has adequate PPE, and it works. For all of this, we are lucky, privileged and grateful.

But now there’s more not knowing. What comes next? When, how, should we open schools? How can we, and how can we not?

Having been home with three children under the age of 10 since mid-March, I contain multitudes: mostly fear, rage, desperation and paralysis. I read Deb Perelman’s collective parental scream in the New York Times and stared at the wall in a fog for what felt like half the day. I don’t remember what it’s like to not have someone chewing inside of my eardrums. I am on a Japanese roller coaster, screaming inside my heart.

Re-opening schools feels necessary, and even the AAP concedes that another year of distance learning carries its own health risks. So I keep looking for a place to settle between risk and control. I haven’t found it.

After a summer of drive-by birthday parades, do I send my children into a poorly ventilated classroom with 27 other kids? Will they be allowed to leave their desks? As Karen Harris points out, the school they’ll return to won’t be the school that they left. Do we choose school over grandparents? What about kids who live with their grandparents? What are we trading? What are we gaining? What are we risking, and for how long? Some of these are privileged questions, but don’t we owe it even more to the kids who need school for meals and security to make it safe?

As a parent, how do you make any kind of re-entry plan, that you feel any kind of OK with, if you have no answers?

As a parent, how do you make any kind of re-entry plan, that you feel any kind of OK with, if you have no answers? How do we manage and evaluate the twin threats of illness and the accumulated effects of social isolation and missed education for our kids when the federal response is a collective shrug?

So maybe here’s my real question: are teachers the new essential frontline workers? This is what stops me.

After all the fear and anxiety and PPE and isolation that our family went through between March and May — the longest three months of my life, but still, three months — how do I ask teachers to put themselves on a kind of frontline for the next year?

We thanked our healthcare workers with signs in windows, cheering from fire escapes, fireworks (enough with the fireworks), and global from-home concerts. Families like mine felt seen, even as we sent our loved ones into the fray.

If we can’t count on each other to wear a mask to the grocery store, how do we protect the people who are going to be protecting our children?

My husband never took a medical school class in pandemic management, but there’s a sense that, as a healthcare worker, he signed on for this kind of thing. I can’t think of a way to make that argument about teachers, cafeteria workers or janitorial staff. There is already so much that they didn’t sign up for, that we ask of them, and that they do because they care.

At the very least, I hope we can rally around educators with the kind of appreciation and reverence that we gave healthcare workers at the beginning of the pandemic. (And PPE would be better.)

But that’s contingent on everyone showing up for the group project. If we can’t count on each other to wear a mask to the grocery store, how do we protect the people who are going to be protecting our children?

In the zombie movies, there’s the vaccine as an end goal, but first they have to get to the next temporary safe zone. I keep thinking, what’s the next location? Can we make it safe? How do we get there together?