Advertisement

Commentary

Why Election Violence Might Erupt — And How To Stop It

I’m writing this from a hotel room in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I am volunteering as an election observer with the League of Women Voters. The president has been barnstorming the state, in an effort to win Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes.

I live in Medford, Massachusetts, but I was born and raised in Milwaukee. My brother, sister and mother still live here. I will never forget my sadness on election night in 2016 when there was such low turnout in Milwaukee. Research published in 2017 shows that Wisconsin’s new voter ID laws had effectively suppressed as many as 43,000 votes in Milwaukee, a majority Black city, and elsewhere in the state. Trump won the state by fewer than 23,000 votes.

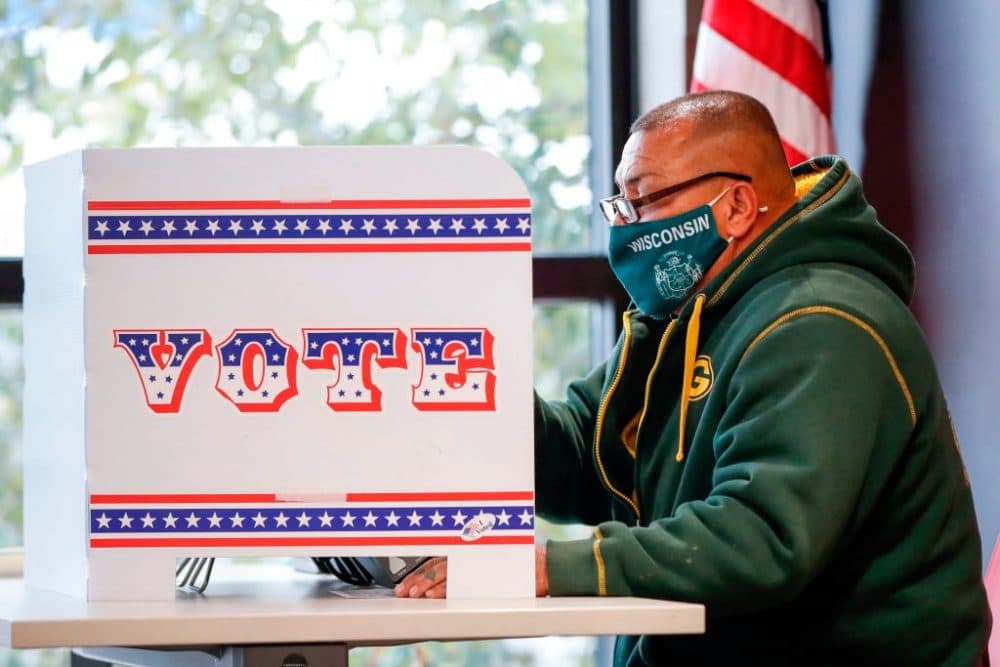

On Tuesday, I’ll be observing at six polling places in Milwaukee County. One of them is at Marquette University where lots of students may be voting for the first time. Another is a polling place in the inner city known as Brewer’s Hill, where my brother votes. It is a racially diverse neighborhood, and my family has owned property there for many decades.

My job is to observe whether the Wisconsin election laws are fairly administered. For example, picture ID and proof of address are required in Milwaukee, but not all forms are acceptable. I will be there to ensure that voters aren’t turned away with valid I.D. and to provide voters with information, if necessary, about casting provisional ballots.

My first shift as an observer was over the weekend. I observed early voting at a public library on the east side of Milwaukee. I’m delighted to report that it was incredibly boring during my time outside and inside the polling station. There were none of the long lines that characterized the presidential primary. Poll workers were helpful and efficient. The most disturbing thing I witnessed was confusion about which doors to enter and exit through.

I will never forget my sadness on election night in 2016 when there was such low turnout in Milwaukee.

But I’m anticipating two big risks on Election Day. The first is the coronavirus — infection and hospitalizations are spiking here. For that, I’m prepared with my collection of KN-95 masks, large eyeglasses and a face shield.

My second concern is about violent unrest, over the next couple of days and as votes are counted. Wisconsin is an "open carry" state, which means that licensed gun owners can display their weapons in many polling places (notably, not schools) as long as the weapons aren’t brandished or pointed at someone in particular.

A report in yesterday’s “Defense One” said people on the right and left of the political spectrum are anticipating the other will come out in force if the election doesn’t go their way. Police departments across the U.S. are preparing for unrest. For the first time in decades, perhaps since Reconstruction, there is a possibility that the United States may see major violent unrest on Election Day and in the days that follow.

I believe that the majority of people on both sides of this election don’t want bloodshed. They want a free and fair election, where all eligible votes are counted.

So, how could it be that if most people on both sides don’t want violence, we may see it anyway?

There are three ways we could get a violent outcome.

First, and most tragically, if both sides fear the other will use force, they could enter what scholars of war call a “security dilemma” — in this scenario, what each side does to feel secure, may appear threatening to the other. This is in part what happened in Kenosha, Wisconsin during the protests in the aftermath of Jacob Blake’s shooting by police.

As “militia” members take weapons to the polls in open-carry states like Wisconsin, to “protect the vote” (on President Trump’s suggestion), people on the left may feel the need to arm themselves. Absent a public commitment on both sides to remain peaceful, these sorts of security dilemmas can escalate quickly.

A second scenario is that amid large scale peaceful protests, a few provocateurs could deliberately start trouble. In this scenario — where it is unclear who escalated — each side will blame the other. If some people on the right are only threatening violence (but not acting violently), to suppress the vote, other people on the extreme may desire to spark a violent confrontation.

[I]f both sides fear the other will use force, they could enter what scholars of war call a “security dilemma” ...

And in a third scenario, violence may arise inadvertently if the police over-react. This is perhaps more likely than we would imagine, precisely because the police have been preparing for violence for several weeks. Out of fear that things will get out of control, law enforcement officers may crackdown on peaceful protesters who refuse to go home or steer clear of federal buildings and other symbols of state power. In this case, an anxious officer or member of the National Guard could inadvertently spark the violence they are preparing to prevent, by perhaps shooting tear gas, rubber bullets or live ammunition into a crowd.

What can be done to reduce the likelihood of violence? It's simple, really.

If we feel the need to be in the streets to celebrate or protest, everybody needs to keep their weapons at home. If there is violence, people should calmly retreat to their corners (literally: walk, don’t run, which only adds the risk of a deadly stampede). Finally, police should follow very strict rules of engagement on American streets, and certainly not attack peaceful protesters. Tear gas and pepper spray should also not be deployed.

Despite the risks, I am glad to be an observer in this historic election. In 1994, I was supposed to be part of an international team of election observers set to witness South Africa’s first democratic elections at the end of apartheid. The right wing threatened violence, and our observation team was cancelled, out of concern for our safety. Despite all the fear, that first election was remarkably peaceful. So was the next one, which I was able to witness in South Africa in 1999. That year, I stood in line with a friend for several hours while he waited to vote. The atmosphere was more than peaceful, it was festive, with singing and people offering tea and cookies to people waiting to vote.

South Africa in 1994 and 1999 was hopeful. Violence is not inevitable here, no matter our divisions. All our votes can and should be counted. I look forward being a witness tomorrow, and to filing what I hope are “boring” reports for the League from each of my assigned polling stations.