Advertisement

Commentary

We're Fighting COVID One-Handed. To End This Pandemic, Get Local Health Officials Better Data

As the first doses of vaccine for the novel coronavirus are administered, the urgent need to track transmission and respond to clusters has not gone away. Instead, the pandemic has exposed a fundamental weakness in our national public health data systems: these systems still can’t capture accurate information about where, why and how the virus is spreading in real-time.

In August, boards of health in Holyoke, where we support COVID-19 response, and in neighboring South Hadley, worked to trace contacts of people that had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The investigations showed that transmission patterns in the adjacent cities were vastly different: cases in Holyoke were mostly in long-term care facilities, while in South Hadley they were mostly from student gatherings.

This type of analysis of how outbreaks are happening locally has critical implications for local health officials — it helps them fine-tune their interventions. And yet, this key information is rarely available to local implementers in actionable reports in Mass., because our public health data infrastructure was never designed to capture it and has not been appropriately upgraded to respond to it.

We must strengthen our data systems if we are to deploy interventions to stop the spread and save lives from COVID-19, as well as be prepared for the next pandemic.

This decision not to share crucial local specificity, renders only a generic response possible.

Local boards of health use the Massachusetts Virtual Epidemiologic Network, the state’s epidemic disease tracking system (known as MAVEN) to collect case details such as age, gender and race. Information from MAVEN is compiled and shared in the form of daily state-wide reports and weekly city-level reports that show only the numbers of tests, cases and test positivity in a given city. These publicly posted weekly reports are too late to be actionable and often contain significant omissions.

Seven months into the pandemic, the state began reporting more granular information that might have facilitated nuanced local public health responses, but only shared aggregate data for the whole state. This decision not to share crucial local specificity, renders only a generic response possible.

MAVEN was established in 2006 to integrate multiple streams of infectious disease information, but it has been challenged by the volume of COVID-19 cases. The Massachusetts Contact Tracing Collaborative, swiftly allocated $39 million to use data management software by Salesforce and Accenture. But local boards of health — also managing large numbers of cases and contact tracing — have had to continue relying on MAVEN. Having two parallel and non-communicating data systems often results in miscommunication and, in our experience, extra effort to de-duplicate records, that hinders rapid response efforts.

Advertisement

These issues are reflective of weak public health data systems nationally. There are huge differences between the rates at which different localities are tracking COVID-19. This matters. The poor quality of national race and ethnicity data relating to COVID-19 has disproportionately affected minority communities. For example, 4% of cases reported in Texas have complete race and ethnicity data, compared to 64% in Massachusetts. Delays in understanding the impact of the pandemic on Black and Hispanic communities has delayed interventions to effectively address their urgent needs.

Data systems should be able to alert on transmission hotspots in real-time ...

Developing systems to provide essential information is possible. Private entities have established detailed data dashboards and cluster reports; Boston University implemented a dashboard that filters test results by campus location and test-taker. Similar data systems exist at the hospitals where we care for patients with COVID-19. These private entities leverage data infrastructure far more complex than what is available to the local boards of health, which are tasked with ensuring the public’s health and safety. We haven’t invested enough in our public health systems -- the same systems we need not just for ending this pandemic, but for responding to the next one.

Up-to-the-task data systems should generate information that reflects the unique data needs of the local community, so that local officials are not just entering data with no actionable information for their communities in return. Data systems should be able to alert on transmission hotspots in real-time, so that we don’t have to wait over a week to see that cases are increasing in gyms, for example. Finally, the systems should be integrated between central command and local response, removing the duplication of effort that parallel systems often cause now.

Earlier this year, Congress provided $500 million in funding to support the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative. Although a promising step, far more state and federal government support will be necessary. Subsequent coronavirus response funding plans should increase support for data systems strengthening and harmonization at all levels.

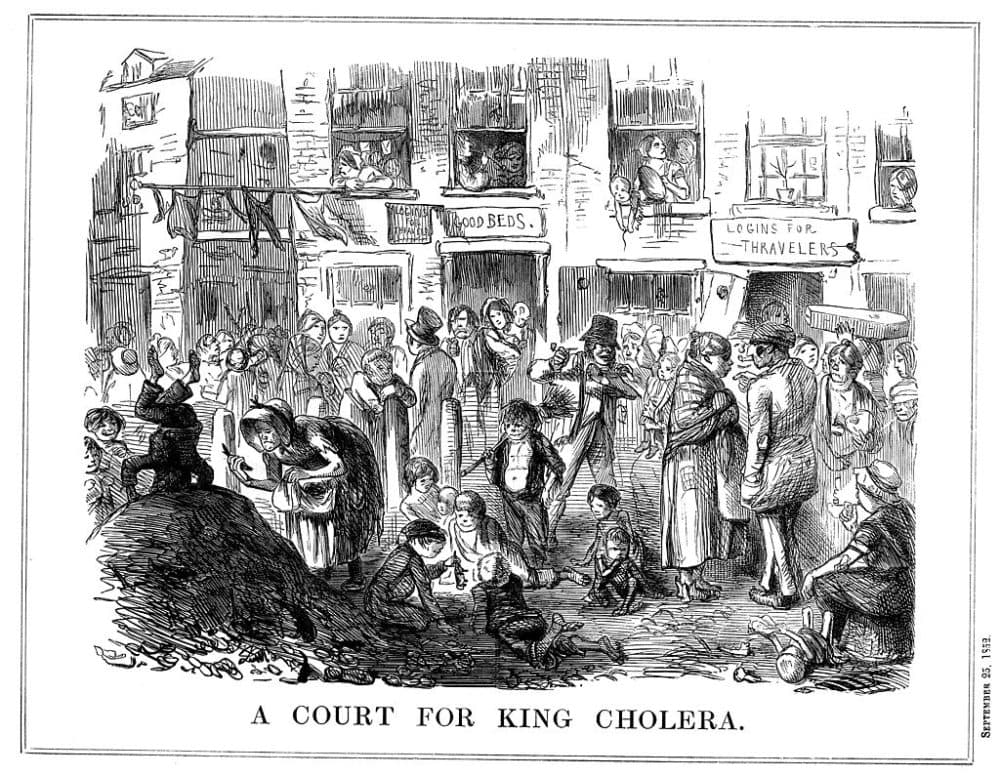

In the 19th century, the British physician Jon Snow created a map of cholera cases in the community, thereby identifying the water pump at the source of that diarrheal disease outbreak. As public health lore goes, he removed the handle of the pump and put an end to that epidemic. His mapping approach to the disease outbreak in 1854 is in many ways more sophisticated than what data systems in local boards of health can produce today.

Accurate, rapid, local and shareable data systems offer the platform from which we can have a more nuanced and targeted pandemic response. If private entities can leverage sophisticated technology to properly track the virus, there is no reason why our local public health institutions and our local communities do not deserve the same.