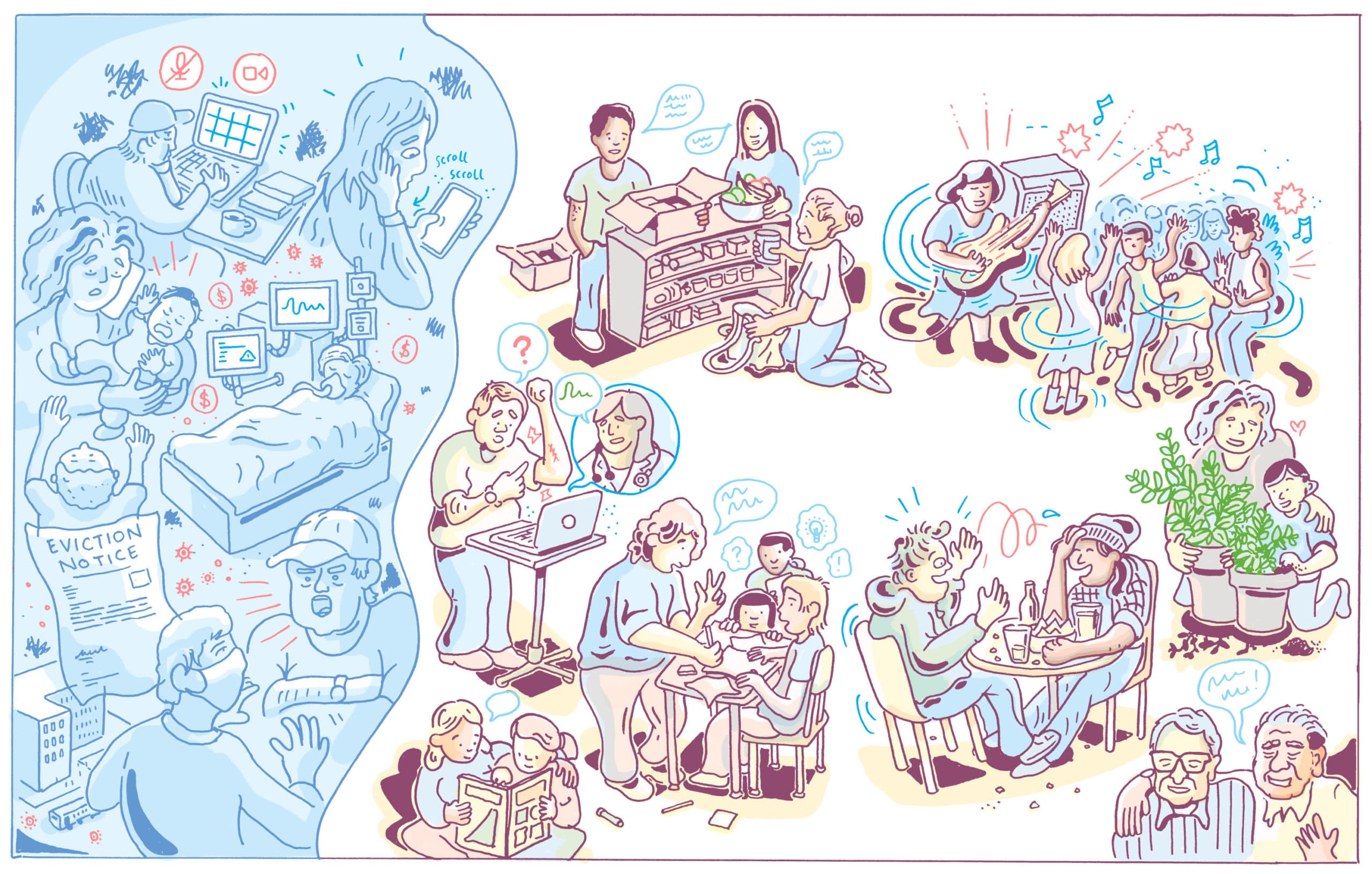

We Asked 10 People To Imagine Life After The Pandemic. Here's What They Said

As more and more people get vaccinated, the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths are finally declining. We know this pandemic won’t last forever.

But — what happens next? Do we just pick up where we left off in March 2020? Or have things changed in a fundamental way?

We asked 10 people to imagine life after the pandemic.

What will work look like after COVID? What about parenting? Friendship? Faith? Will our understanding of public health change, as epidemiologists race to get ahead of the next pandemic?

The truth is, nobody knows exactly what comes next. Uncertainty continues to reign. But for the first time in a long time, it feels like we can reasonably contemplate the future — we are no longer locked in the “perpetual present.”

Read through each contributor's short essay below, or jump around to different topics using this navigation:

I’m Ready To Double Down On The Joys Of Physical Friendship

In the beginning, we had Zoom, and it was fine: virtual happy hours and online game nights that kept friendships alive when we had to be physically apart. But the pandemic separation couldn’t last.

In late spring, I took my first illicit walk with friends; we wore masks and glanced sideways to see if we’d be shamed. By summer, we were venting our frustrations during walks around a pond, holding birthday dinners outdoors, taking socially-distanced selfies with the timers on our phones. When winter came, we layered up like ice fishermen and huddled around fire pits on 30-degree nights.

I want to double-dip in the guacamole. I want to sip your cocktail to see if I like it, too.

Joanna Weiss, Editor, Experience Magazine

We’ve needed each other, and that’s good to know. One of the hardest things about COVID has been the way it rendered friendship dangerous — so many transmissions springing from in-person gatherings, as friends came together despite the directives. You can condemn all of those people as cavalier about public health. Or you could see their lapses as a feature of humanity.

We’ve learned, this past year, that connection isn’t the same when it’s remote. And while many of us have broken the rules at least once or twice, we should acknowledge the lengths we’ve gone to see each other in relative safety.

When the COVID threat is gone, I predict that we’ll double down on the joys of physical friendship. I want to live dangerously with my besties. I want to double-dip in the guacamole. I want to sip your cocktail to see if I like it, too. I want to scream together into a karaoke microphone. I’ll pick the first song: “With a Little Help From My Friends.” -- Joanna Weiss, Editor, Northeastern University's Experience magazine

We Need To Think About 'Health' In A New Way

In some ways, COVID-19 will be remembered as a triumph of biomedical science. We developed safe and effective vaccines — something that usually takes a decade or more — in less than a year. And, despite a number of stumbles, improved therapeutics reduced mortality from the virus in hospitals more than fourfold in a matter of months.

But COVID-19 provided, even more memorably, a terrifying and revealing view of our failure to create a world that generates health.

Once this pandemic ends, we’ll undoubtedly be having more conversations about how to prevent future pandemics, and ensure a healthier future. But will we be thinking about health in a bigger sense?

Fundamentally, health is not health care.

Sandro Galea, Dean, Boston University School of Public Health

Fundamentally, health is not health care. Decades of underinvestment in healthy environments, adequate education, safe workspaces and livable wages resulted in a country that was unhealthy and vulnerable to the ravages of a novel virus. The U.S. has had the highest per capita rate of COVID-19 infections throughout the pandemic.

This moment should teach us that avoiding the next pandemic will require us to rethink how we approach health, so there are no haves and have nots. It’s recognition that we cannot be healthy, unless we build a world with safe housing, good schools, livable wages, gender and racial equity, clean air, drinkable water, a fair economy.

It’s time to change how we think about health. -- Sandro Galea, Dean, Boston University, School Of Public Health

The Pandemic Deepened The Lessons Of Aging

My husband and I are in our late 60s. Fed, housed, and able to freelance, we’ve weathered the past year with gratitude and relative ease. But like many of our peers, the pandemic has intensified our feelings about how we want to live the rest of our lives, in intentional community. Our choices feel quite personal, but they are representative of emerging trends.

In a post-pandemic future, we can expect to see the biggest change in where and with whom the elderly live. With 40% of all fatalities, the virus’s impact on residents of nursing homes has been earth-shaking, fueling people’s desire to age in place or live in settings where mutual aid is the norm. Stunned by the isolation of the pandemic, most of the new recruits to our co-housing community have been people over 60. Local programs supporting in-home care are on the rise, and state and federal programs paying family caregivers are also likely to expand.

Technological advances will also pave the way for aging in place. Telehealth is more widely accepted, and devices like smart speakers will soon notify loved ones if you call out for help. Indeed, the pandemic has highlighted our intergenerational interdependence. With schools and daycares closed, working parents have moved in with their parents so that they can help mind the kids, and many adult children, having been deprived of the ability to see their quarantined loved ones, are determined to pre-empt that scenario in the future.

Advertisement

Don’t take your family and friends for granted. Protect your health. Accept that you’re going to die and live accordingly.

Julie Wittes Schlack, Writer, Retired Marketing Executive

Will market volatility make it less likely that people will retire? Or will the COVID-induced knowledge of our own vulnerability fuel our urgency to pursue what we value versus what we’re paid for? I don’t know. But I do know that COVID has deepened the lessons that aging inevitably bestows: Don’t take your family and friends for granted. Protect your health. Accept that you’re going to die and live accordingly. -- Julie Wittes Schlack, Writer

Mothers Continue To Hold Up A Broken System

I never harbored any illusions about living in a culture that values mothers. From day one, my experience as a mom has been peppered with moments of rage and periods of existential crisis. I love the love of motherhood, but the work of mothering is mostly unsupported and un-respected. The nonstop parenting, teaching, cooking, cleaning that mothering has entailed during the pandemic has confirmed that this type of labor is also, for me, largely a drag.

Although the beauty of motherhood is widely celebrated on Instagram and elsewhere, our primary value lies in our ability to raise the next generation of workers and consumers. As the pandemic has shown, mothers’ needs don’t really seem to matter. Our needs don’t impact the bottom line.

The pandemic calcified my fury that mothers are expected to hold up the whole of a very broken system, while being given nothing in return.

Sara Petersen, Writer

The pandemic calcified my fury that mothers are expected to hold up the whole of a very broken system, while being given nothing in return. In the past year, we’ve seen a flurry of essays and reporting showing that women and mothers have been disproportionately burdened with the impossible task of keeping society afloat (the latest New York Times series is appropriately titled, “The Primal Scream.”) The coverage is affirming and necessary, but not a single mother I know has been surprised about any of the awful statistics or heartbreaking personal stories.

When this is over, I’m looking forward to no longer being the sole provider of all things to my kids. But I also wonder if the tidal wave of momentum inspired by the pandemic will carry us through to something better than think-pieces.

We need equal and fair pay for mothers. We need humane prenatal and postnatal care, and paid parental leave legislation. We need to reform our racist health care system that has led to countless Black mothers’ deaths. We need to end the debate on whether women’s reproductive rights are actual rights. And we need to radically rethink our capitalist system, which uses mothers and other care workers to uphold the primary concerns of buying and selling, while denying them adequate compensation — or even cultural respect for their indispensable work.

I wonder if women’s rage will coalesce into action. I hope so. -- Sara Petersen, Writer

The Pandemic Forced Us To Take Faith Into Our Own Hands

I spent many nights in the last year contemplating God’s wisdom and purpose, while fielding the despair and weariness of many Muslims who sought my counsel. They wanted to know, was COVID a pandemic or the plague, and what was the difference? Was it God’s wrath or God’s cleansing? Was there a collective spiritual remedy to make it all go away?

As we begin to see a light at the end of the tunnel, I wonder if and how our faith as Americans has changed.

It was no coincidence that the height of the pandemic in Massachusetts last spring struck during the Holy days of all three Abrahamic faiths. Easter, Passover and Ramadan came and went in our homes. We had to learn to celebrate without the pomp of public worship. People who attended church, temple and mosque — but never took it upon themselves to utter their own personal prayers — were forced to petition God themselves.

God forced us to stop our schedules to give us a moment to take faith into our own hands...

Taymullah Abdur-Rahman, Imam

I watched my own teenage children reluctantly read the Quran aloud at home for the Eid Holidays (without the help of the entire mosque). As life returns to normal, I suspect we’ll have a deeper appreciation for our respective worship-communities and the spaces of comfort they provide us.

I also think the goals of the American faithful have shifted slightly. We want a little less of the world now, and more authentic connections with real people. God forced us to stop our schedules to give us a moment to take faith into our own hands — and for the most part we did.

Now I believe God will allow us to embrace one another again, both literally and figuratively. -- Taymullah Abdul-Rahman, Imam, Massachusetts Department of Correction

I Worry Education In A Post-COVID World Won't Change Enough

My greatest fear is that K-12 education in a post-COVID world will not change enough. As an 8th grade teacher, the past 12 months have completely changed how I approach my work.

In-person, Ms. Avashia was all about urgency and rigor and content, content, content. Pandemic-teaching Ms. Avashia moves much more slowly with her students.

Now, I focus my efforts on deep learning, instead of coverage of pages of standards. Each day, we work through one meaningful task, instead of trying to speed through three or four. We play more in class — using riddles or visual puzzles, telling jokes in the chat, changing our Zoom profile pictures, to make each other laugh. I’ve even dressed up in costumes multiple times this year just to bring kids some moments of humor.

Teaching during the pandemic has pushed me to be so much more human with my students, and to teach into their humanity. And that, at its core, is completely different from how education has traditionally been structured in our society.

I believe deeply in the democratic cornerstone of public education. But we have never succeeded in fulfilling its promise for all of our students, particularly those students most impacted by racial and economic injustice in our country.

Our school buildings have been sites of over-policing of students’ bodies, of adultifying and criminalizing adolescent behavior, of reducing student learning down to what can be demonstrated on standardized tests.

We have an opportunity to walk away from those practices forever. To build educational settings that are grounded in students’ humanity, and designed with their voices, needs and interests at the center. To ensure that our schools are structured and staffed to prioritize relationship-building, robust mental health services and targeted academic supports. We can affirm the notion that schools are cornerstones of both our democracy and our communities, by fully funding the work that we as a society are asking them to do.

We can affirm the notion that schools are cornerstones of both our democracy and our communities...

Neema Avashia, Teacher, Boston Public Schools

We can do all of this. We should do all of this. The question is: Will we? -- Neema Avashia, Teacher, McCormack Middle School

COVID Forced Companies To Be More Flexible. Will They Harness The Lessons Learned?

The “culture of time” at many companies wasn’t healthy before the pandemic. Some organizations were trying to address bad habits (no time to think, everything-gets-done-by-meetings culture), before new problems like Zoom fatigue and FOLO (Fear Of Logging Off) took hold.

The pandemic accelerated a comeuppance about how the workplace can and should evolve. I think the lessons we learned this year will almost certainly lead to greater flexibility in the long term.

This year proved that a lot of work can be done remotely. It also made clear the handful of things better done in person — bonding, mentoring and new relationship building. Companies will need to bring people together regularly to ensure the kismet that happens in 3D.

The pandemic accelerated a comeuppance about how the workplace can and should evolve.

Julie Morgenstern, Author, Productivity Expert

Every worker needs time and space for quiet work, time and space for meetings, and time and space for informal and more casual communication. This was true pre-pandemic, and it’s still true. Future workspaces are likely to reflect these needs: large library-like areas where people can go to do their thinking (like the quiet car on a train); lots of formal and informal meeting areas; and administrative spaces to deal with email and chat with coworkers.

Back-to-back meetings — 7 to 10 Zooms a day — is not an effective way to work. It leaves no time to think, or to actually do the work generated in those meetings.

Companies seem to have finally learned that their employees are whole people. Work is part of their lives, and their lives beyond work are essential and valuable to their well-being. In our post-COVID world, I suspect the role of chief people officer and chief wellness officer will evolve, and be seen as a critical role for a healthy organization.

COVID forced organizations to change. It forced them to be more flexible, and that experience highlighted what went missing in a 100% remote environment. The job of leaders is now to stop, reflect and embrace what we discovered in the last year, and consciously build workplaces and workspaces that harness those lessons, to enable companies to achieve their goals and workers to feel fulfilled. -- Julie Morgenstern, Productivity Expert, Author

We Must Do Right By The Communities, Including Chelsea, That Suffered The Most

I’ve lived in Chelsea my whole life, but I don’t remember my community ever being in the news as much as it was during the first peak of the pandemic. With the highest infection rate in Massachusetts — and blocks’ long lines of people waiting for food — Chelsea was on display for the world to see. Even my family in Argentina saw news reports of our city being slammed by the raging pandemic.

During those difficult days, people opened up their hearts for the residents of our community. Those of us involved in addressing the coronavirus pandemic in Chelsea, received an outpouring of support through donations, volunteering, well wishes and prayers for recovery and hope.

Other low-income, ethnically and racially diverse communities like Chelsea faced the same wrath. Years of structural oppression and racism leading to health, environmental and economic disparities, have made the effects of COVID-19 so much more pronounced.

My post-pandemic hope is that the hearts and minds of those outside of these cities remember how much communities like Chelsea have sacrificed. Will you remember us in six months? Six years? Sixteen years from now?

Will the people of Massachusetts continue to have communities like Chelsea in their hearts and minds?

Roseann Bongiovanni, Executive Director, GreenRoots

Will the people of Massachusetts continue to have communities like Chelsea in their hearts and minds? Will you reflect on our disproportionate environmental and industrial burdens, poor public transportation, food insecurity, housing instability and low wages for essential workers? Will others say, “We can shoulder a little bit of the burden, so it’s not all on the backs of low-income communities of color?”

We must learn from the past year, and from the reasons for Chelsea’s soaring infection rates. We must pass laws to protect environmental justice communities. We must say “no” to new toxic facilities. We must prioritize the health and well-being of all people, but particularly those who have faced oppression, discrimination and racism, which caused these health disparities. -- Roseann Bongiovanni, Executive Director, GreenRoots

Will Art Remain The Unifying Force It’s Always Been?

I’m sitting behind my screen, fractured from the world.

I don’t feel the need to see other people as much as I did earlier in the pandemic. Has something happened to me on a molecular level? Is the isolation hitting other writers and artists the way it’s hitting me?

We already live in a world of separate platforms. News broadcasts spin the same events in different ways for different people. The platforms dictate what we see based on what the platforms think we want to see. They strut the arrogance of knowing us better than we do. And now the pandemic has further alienated all of us.

I hope the isolation we’ve endured this year won’t stunt our ability to connect to each other.

Desmond Hall, Novelist, Visual Artist

This worries me, because I love when artists create the specific that’s felt universally. I wrote a book about a boy and his family in rural Jamaica. So far it has resonated in other parts of the world. But if we continue to be so isolated will we be too separated to partake in varied experiences?

It was only a short while ago when some Hollywood execs deemed a movie like “Black Panther” was too ethnic to have widespread appeal. They doubted that the specific had universality. The film proved them wrong, but what if we continue to grow apart, divided? Will some art be discarded as irrelevant because large swaths of people can’t relate, can’t see the universality?

I believe in art as a unifying force, as a medium that reveals our commonalities and reasons to strive together. I hope the isolation we’ve endured this year won’t stunt our ability to connect to each other. -- Desmond Hall, Author, Visual Artist

Behavior Change Won't Be Enough To Avert Climate Catastrophe

With more than half a million lives lost in the U.S., the COVID crisis has yielded a sobering lesson about human resistance to change, even in the face of devastating consequences.

Wearing masks in public? A no-brainer. Avoiding large indoor gatherings? Ditto. Yet when official directives and common sense have impinged on individual choice, too often they have collided with indifference, indignation and defiance.

Some wonder if there are lessons to be learned from the pandemic as we seek to avert the worst ravages of climate change. With many working remotely rather than traveling daily to their offices, reduced commuting has doubtless contributed to the past year’s drop of more than 10% in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a pretty sure bet, though, that commuters will refill our highways, with more people than ever traveling by car for fear of infection on public transit.

Air travel, too, is likely to rebound as business trips come back into vogue and leisure travelers take to the skies.

The COVID crisis has yielded a sobering lesson about human resistance to change, even in the face of devastating consequences

Philip Warburg, Senior Fellow, Boston University Institute Of Sustainable Energy

Rather than placing our bets on behavioral change, we need to demand of government and industry what we cannot expect of ourselves. All levels of government must require a true gearing-up of renewable energy as our primary electricity source.

In addition, the federal government must mandate a shift to cleaner, leaner motor vehicles — a challenge bigger than simply electrifying the behemoths that now roll off our production lines. And governing bodies at all levels must embrace an unprecedented commitment to energy justice, making it possible for low-income people to make their homes more efficient, buy energy-efficient appliances, and install solar power on their rooftops and in their communities.

It would be folly to rely on new patterns of human behavior emerging from the COVID catastrophe to address climate change. We need to make an all-out investment in retooling the engines of our society. -- Philip Warburg, Senior Fellow, Boston University Institute Of Sustainable Energy

Amy Gorel, Lisa Creamer and Kathleen Burge helped with the production of this piece. The audio essay was was produced by Cloe Axelson, with help from David Greene; it was mixed by Michael Garth.