Advertisement

Commentary

To Survive Rising Seas, Boston May Need To 'Make' Land Again

Land-making is part of Boston’s identity: one-sixth of the city is built on ground that was once underwater. And now our history is coming back to haunt us.

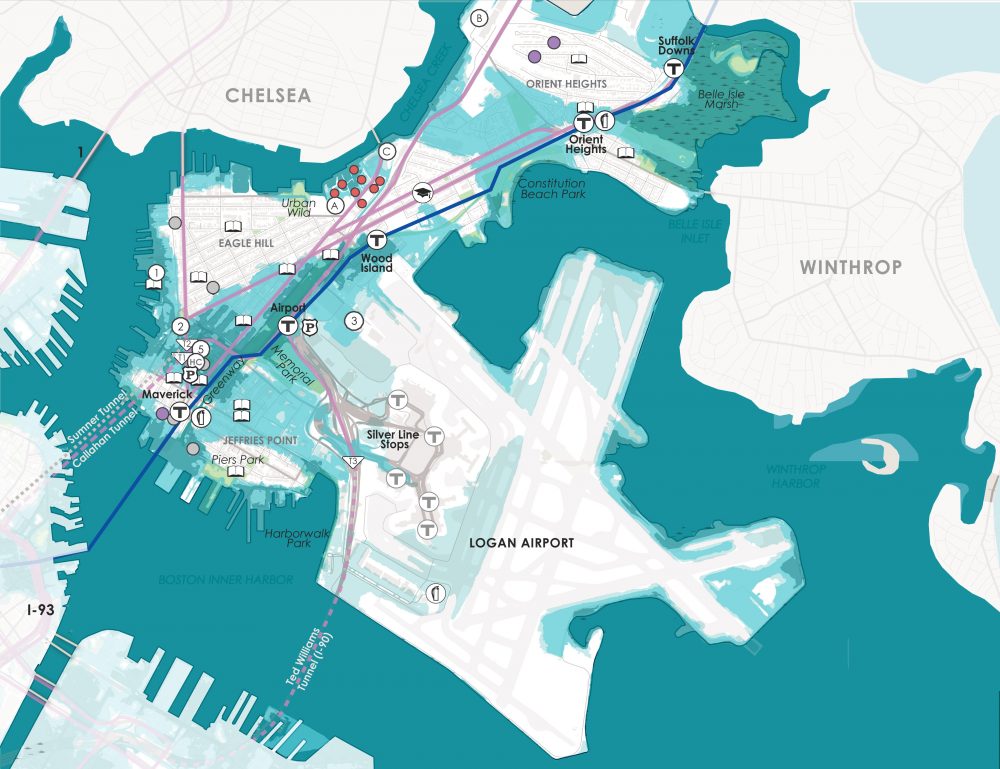

By building on low-lying land, the city created its own future floodplain. Many of the areas most vulnerable to flooding and storm surges due to sea level rise are built on landfill, including the Seaport District, parts of East Boston and the Downtown waterfront. Now the city faces some tough choices. How can we protect vulnerable areas against damaging storms and rising tides? How do we decide where it makes sense to advance into the water and where to pull back?

Expanding the shoreline is a practice we tend to think of as outmoded and harmful; laws and regulations that protect coastal resources now make it all but impossible to “fill” along the shoreline. But new fill may be needed to achieve the city’s vision for a waterfront that will continue to thrive as the climate changes.

Remember, Boston was once a small peninsula of land in a watery landscape filled with shallow mudflats and marshes. Over time, those shallows were transformed into land by constructing seawalls and filling behind them with dirt, gravel, dredged harbor sediment, trash and other materials to raise the land just a few feet above high tide.

An early Colonial law gave private landowners in the nascent port the right to build into the water to develop a shoreline of wharves and piers. As the city grew, some wharves were filled in, and land was added for new purposes: to create new neighborhoods, like the Back Bay, expand industries, site transportation infrastructure and cover over polluted water.

The first wave of shoreline regulation came in the 19th century, when government leaders became concerned about preserving Boston Harbor for navigation. In the 1830s, the state laid out the first harbor lines prohibiting filling beyond certain limits. Thirty years later, the state formed an administrative body to oversee and approve all development in tidelands, a program eventually known as Chapter 91. Eventually, the federal government gained the power to keep harbors and major rivers clear for navigation.

By the 1970s, a new wave of federal and state environmental laws and regulations prioritized natural resources over development. No single law bans fill outright, but all together, they create a layered system of permitting, licensing and certification that make it extremely difficult to win approval for fill projects.

Those are the laws on the books today. A project that fills along the shoreline, for instance, may require a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, an order of conditions from the local conservation commission, a Chapter 91 license, environmental impact review and certification from the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act Office, and review by the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management. Additional state and federal agencies weigh in on compliance with laws that protect endangered species, fisheries and historical resources.

Advertisement

A generation ago, the key priority of regulation was to halt shoreline change. But shorelines are changing whether we like it or not.

Beyond the letter of the laws, the lengthy approval process — and the tendency of regulators to make discretionary decisions against fill — discourage any alterations to the shoreline.

Though the system can seem onerous, it provides an important check against development that threatens coastal habitats and public access to the waterfront. Increasingly, though, people working to protect ecosystems and communities from the impacts of climate change are expressing frustration with current coastal management policies. Many want to see greener, nature-based flood protection systems like living shorelines (protected shorelines made from natural materials like earth, rocks, or sand that can support vegetation and provide habitat), but they can be challenging to permit because they can involve adding fill and altering existing natural resource areas.

Visions for protecting Boston have often focused on adapting the shoreline in a way that draws on nature, rather than relying on “gray” flood protection systems like higher seawalls or a massive barrier in the Harbor. Nature-based solutions range from site-specific adaptations like restored marshes and berms (raised strips of grassy land) to grander visions like a network of parks along the shore. Some of these visions lie outside the realm of what could be easily permitted today.

The city’s plans for protecting vulnerable neighborhoods through Climate Ready Boston emphasize permittable designs, but some ideas would require using fill to create new parkland and protective wetlands, among other things, that extend past the shoreline.

Boston adopted a Wetlands Ordinance in 2019 that explicitly directs the city’s conservation commission to allow fill for flood protection projects, particularly those that create new habitat along the shoreline. But local regulatory changes don’t supersede the federal and state restrictions already in place.

Experts involved in waterfront advocacy, development and climate adaptation have told me that some fill is needed to protect Boston, particularly if the city decides to pursue a greener shoreline. But visions about the proper use and scope of fill vary, raising some key questions. If limited fill is allowed for nature-based flood protection, what exactly counts as a “natural” shoreline? What about a concrete wall topped with a grassy berm to create new open space? Should the city push farther into the water to create protective parks that could expand the public realm beyond the Harborwalk? And who would pay for it? Would financing a new public realm require giving rights to private developers, much like colonists gave rights to wharf builders in the 1600s, and at what cost?

Fill is a touchy subject in Boston Harbor, and these debates have had limited public airing. But given the slow pace of regulatory change, we need to discuss these choices now. A generation ago, the key priority of regulation was to halt shoreline change. But shorelines are changing whether we like it or not. We need a means to permit shoreline projects that anticipate these changes in a way that enhances ecosystem services, provides open space and protects people from flooding.

In Boston, we particularly need solutions that don’t perpetuate the social, economic, and racial inequalities that we see in the city’s gentrifying waterfront neighborhoods. Whether to fill or not is just one of the decisions that face the city in the future, but it’s a decision that’s important to get right.