Advertisement

Commentary

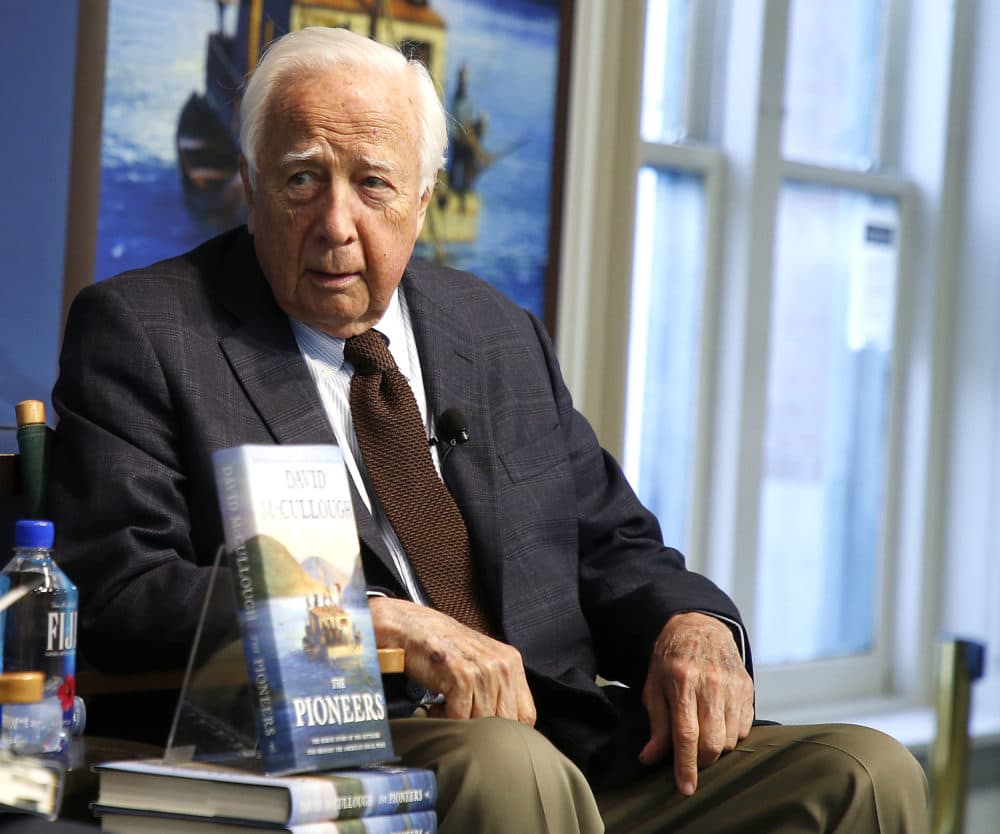

David McCullough taught us that history is for everyone

David McCullough, who died this week, introduced generations of readers to the joy and excitement of history. My favorite book remains "The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge," published in 1972. McCullough made the bridge the central character of the book — an extension of the vision of engineers John Roebling and his son Washington Roebling, and the countless workers who labored and died during its construction.

McCullough conveyed the sights, sounds and smells of 19th-century New York City, from the depths of the bridge’s foundations, below the East River, to the laying of the suspension cables. The book sparked my imagination and, even after 608 pages, left me wanting to know more.

“History, really, is an extension of life," McCullough wrote. "It enlarges and intensifies the experience of being alive, like poetry and art or music.”

McCullough wrote this in his essay “Why History?” published in 1995. It is a subject that McCullough, who covered a broad swath of American history, including Pulitzer-Prize-winning biographies of presidents Harry Truman and John Adams, returned to regularly. The essay reflects his love for history and the importance that McCullough attached to history education, but it also highlighted his concern that, “We … are raising a new generation of Americans, who to an alarming degree, are historically illiterate.”

“It has been coming on for a long time,” McCullough warned, “like a creeping disease, eating away at the national memory. While the clamorous popular culture races on, the American past is slipping away, out of sight and out of mind. We are losing our story, forgetting who we are and what it’s taken to come this far.” McCullough shared stories of meeting college students who couldn’t identify George Marshall or were unaware that the original 13 colonies were all located on the eastern seaboard.

Looking back, we can now view these early warnings not solely as a sign of a growing historical illiteracy, but as the first cracks in what historians refer to as the “consensus” narrative of American history that had dominated American culture since the 1950s. After all, McCullough is not the first person to suggest that Americans don’t know enough or care about their own history.

In 1943, at the height of WWII, The New York Times published a survey of college freshmen from around the country and found they “know almost nothing about many important phases of this country’s growth and development.” Sixteen percent of the 7,000 respondents were able to identify Thomas Jefferson as the president who brokered the Louisiana Purchase. Only 6% could name the 13 original colonies. The survey focused overwhelmingly on the history of presidents, inventors and leaders of business. A few references to women punctuated the survey while Black people and other minorities were noticeably absent.

The content of the survey would come to frame a consensus narrative of the American past, whose purpose was to unite (mainly white) Americans during the Cold War with the Soviet Union around a belief in “American Exceptionalism” — the conviction that progress was inevitable and freedom and democracy would always push the nation forward.

McCullough graduated from Yale in 1955. This consensus view shaped his writing, including his choice of topics, how he understood the broad sweep of American history and especially the civic importance he attached to history education. But looking back, we can also see the clear limitations and distortions of this narrative framework. Generations of American children were taught the "Lost Cause" view of the Civil War, which celebrated Confederate generals as heroes and minimized the importance of slavery, emancipation and the contributions of African Americans to winning the war. Many textbooks cast African Americans as unprepared for freedom and political participation during Reconstruction — a view that continued to justify legalized segregation throughout much of the country into the 1950s and '60s.

Subjects that threatened national unity or threatened the nation’s belief in itself as the “leader of the free world” were minimized or ignored altogether. It wasn’t just the subject matter itself that defined this consensus view, but who could claim the mantle of "historian." Historians were overwhelmingly white and male.

This is the view of the American past against which McCullough and others measured the level of interest and knowledge of American students and the general public by the 1990s.

But as a historian and history teacher with over 25 years’ experience, I remain optimistic.

I find that students today are deeply interested in history and its importance in addressing many of society’s problems. This interest has been fueled by a broadening of the history curriculum and the many new voices that now occupy a space in the fields of historical scholarship, public history and history education — voices that have long been blocked because of their gender, race, etc.

These perspectives and questions have forced us to confront uncomfortable subjects such as the history and legacy of slavery that have been buried for far too long. At the same time, they have highlighted a more diverse cast of American heroes who struggled to push the nation to live up to its founding ideals.

This is not to suggest that we don’t face challenges. Americans remain deeply divided politically and culturally over how American history should be understood and taught in public school classrooms. These debates raise some of the same concerns that animated McCullough: What is the purpose of a history education? Is it possible to craft a historical narrative that unites Americans from different backgrounds around a new shared past?

Any attempt to answer these questions must begin by acknowledging a truth that David McCullough embraced throughout his career: History is for all of us.