Advertisement

Commentary

Art reminds me that illness is part of our shared landscape

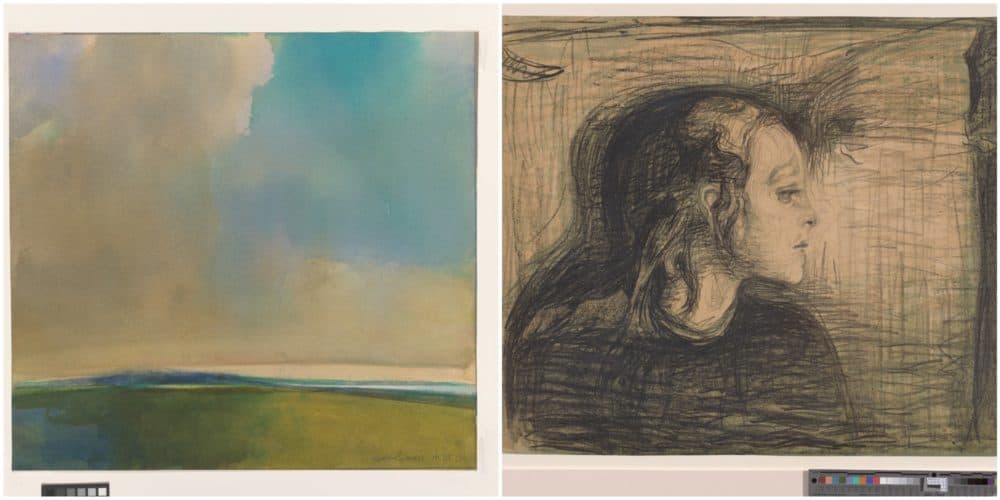

The exhibit begins with a painting of a place I think I recognize: a sapphiric ribbon of wave twisted into sand; turquoise sky obscured by thunderheads. I edge closer, trying to guess which beach the artist captured — I’m at the RISD Museum, after all, in the Ocean State. Instead, a plaque informs me Thomas Sgouros did not paint this scene from sight — his was fading under the effects of macular degeneration — but from memory. The seascape is an amalgamation of all those he once saw. As such, it’s an open canvas, allowing the viewer to locate their own memories in its swirls of jewel green and burnished gold.

Beyond the painting, I catch sight of another familiar image: "The Sick Girl: The Artist's Sister" by Edvard Munch. I’d written about Munch’s lifelong illness while I struggled with recurring symptoms that followed a COVID-19 infection. I’d returned, again and again, to this depiction of his sister Sophie dying from tuberculosis — a disease that threatened the artist’s own health. In the museum’s lithograph, the trauma of the sickroom is translated in dark, expressive lines that communicate not only the hollow stare and matted brow of the sick girl, but also the emotion felt at her bedside.

“When I first proposed this exhibition, there was some uncertainty around if we would find enough representations in the collection,” Conor Moynihan, assistant curator of prints, drawings and photographs at the RISD Museum, told those of us on a tour of “Variance: Making, Unmaking, and Remaking Disability.” “The truth is, illness and disability are always among us, we just have to know how to look for it.”

Moynihan’s curation helps viewers see what is ever-present in society, and all the more so during a pandemic. Disability has always been a part of human experience, as the exhibit, which spans centuries, shows us. The pandemic offers a microcosm of time through which we can examine how culture responds to the prevalence of disease and difference. While COVID has take more than six million lives and disabled or debilitated millions more, many of those losses are overlooked in a country whose government is driven by economic incentives to return to “normal.” This elusive status quo fails to recognize the lives of the ill, disabled and otherwise vulnerable by refusing to protect and value difference.

The pandemic has brought -- continues to bring -- a new wave of the chronically ill among us, offering an opportunity to see what has been here all along.

"Variance" frames disability not in terms of a desired normality, but instead asks us, as Moynihan writes in a companion piece published in the journal Manual, “to consider what is gained, generated, or open to imagination by embracing disability as a critical framework through which to experience the world.” His curation brings together various representations of embodied experience: some stigmatize, such as William Hogarth’s 1735 view of the madhouse; others cast a more compassionate gaze, like photographer Salvatore Mancini’s 1984 images of the institutionalized in Rhode Island. The exhibit ranges from art that connects the viewer to the vulnerability of the sick — Dominic Quagliozzi’s canvas is the delicate tissue we all perch on at the doctor’s office — to work that challenges the very idea of vulnerability with the open gaze of artist Robert Andy Coombs in “Cuddle on Couch,” a photograph of an intimate embrace of his disabled body.

I’d come to the exhibit to understand how others found ways to articulate illness. When I first fell sick in March 2020, there was no public recognition of COVID's chronic forms. Doctors encountering the virus for the first time had little knowledge about post-viral illness, causing them to dismiss my ongoing symptoms. Others denied the pandemic, or downplayed its dangers, undermining the daily struggle that was quickly consuming my life.

Advertisement

As a writer, I became frustrated with the gulf that opened between myself and the medical professionals standing skeptically by as I shifted on the thin crepe between my thighs and the chill of the exam table. I found it difficult to communicate to friends the strain of an illness that reared and relented month after month. I felt powerless to change the behavior of others, even when their refusal to get vaccinated or wear a mask meant my illness might be perpetuated: By reinfection and by the continual need to get boosters — which tend to exacerbate my symptoms and cause months-long setbacks.

I found refuge in writing about my condition, which relieved me of its heavy burden of silence and connected me with other chronically ill people, many of whom felt the same lack of agency. I became interested in how artists addressed the unique challenge of expressing illness, and discovered I was not speaking into a void; other voices were already there. I recognize them in the photographs and paintings of the “Variance” exhibit, I read them in favorite works of literature — in Mrs. Dalloway’s heart, for example, forever weakened by influenza. I hear them on the news, and I meet them at the office. The pandemic has brought — continues to bring — a new wave of the chronically ill among us, offering an opportunity to see what has been here all along.

When the curators at RISD examined the museum collection through the lens of illness they discovered, as Moynihan puts it: “abundance.” The archives had been, of course, rife with depictions of disability and difference, as any assemblage of human expression will be. Illness is a part of every life, in one form or another, and it is one of the great tasks of art and literature to convey the physical sensations, deep isolation and novel perspectives of its ever-varying manifestations. The other challenge lies with the viewer: to recognize this landscape as one to which we all belong.