Advertisement

Commentary

Boston’s only Black hospital was founded in 1908 — in the South End apartment building where I lived

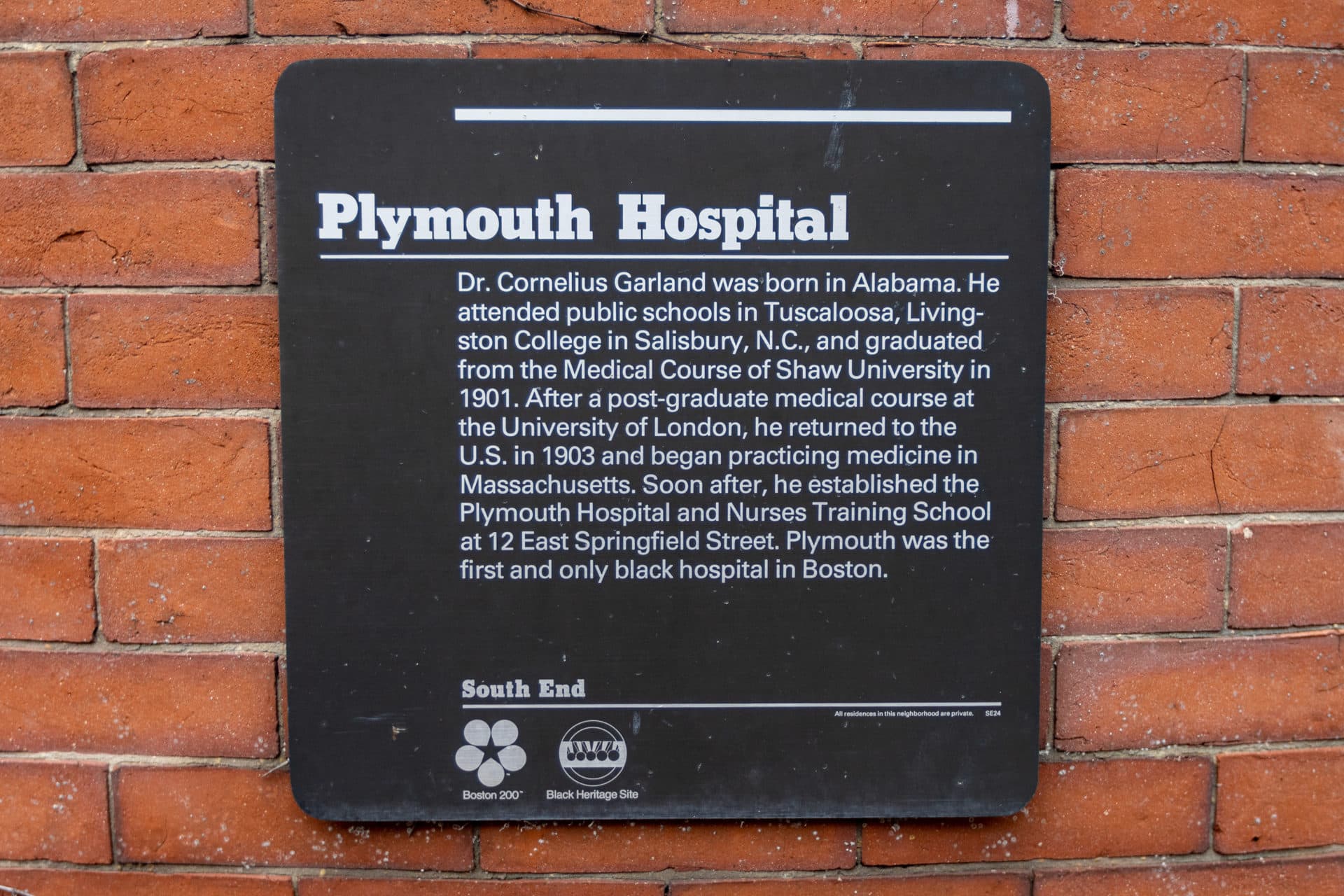

East Springfield Street in Boston is lined with three-story brownstones, most of them completely unremarkable, their brick facades and wrought iron railings blending together under a canopy of trees. Number 12, where I lived for five years, is just like all the others — or so I thought. Moving from San Francisco to Boston, I signed the lease after viewing the apartment on FaceTime. I didn’t see the plaque outside until I moved in.

It says that from 1908-1928, Dr. Cornelius Garland, a Black physician from the South, operated Plymouth Hospital and Nurses Training School, “the first and only Black hospital in Boston,” in the very building where I lived.

Looking around my apartment, I couldn’t fathom how this small building had functioned as a hospital. The story I imagined behind that plaque intrigued me, both as a fiction writer, and in my day job as an editor at a health care journal. I kept thinking about Dr. Garland. Who was he?

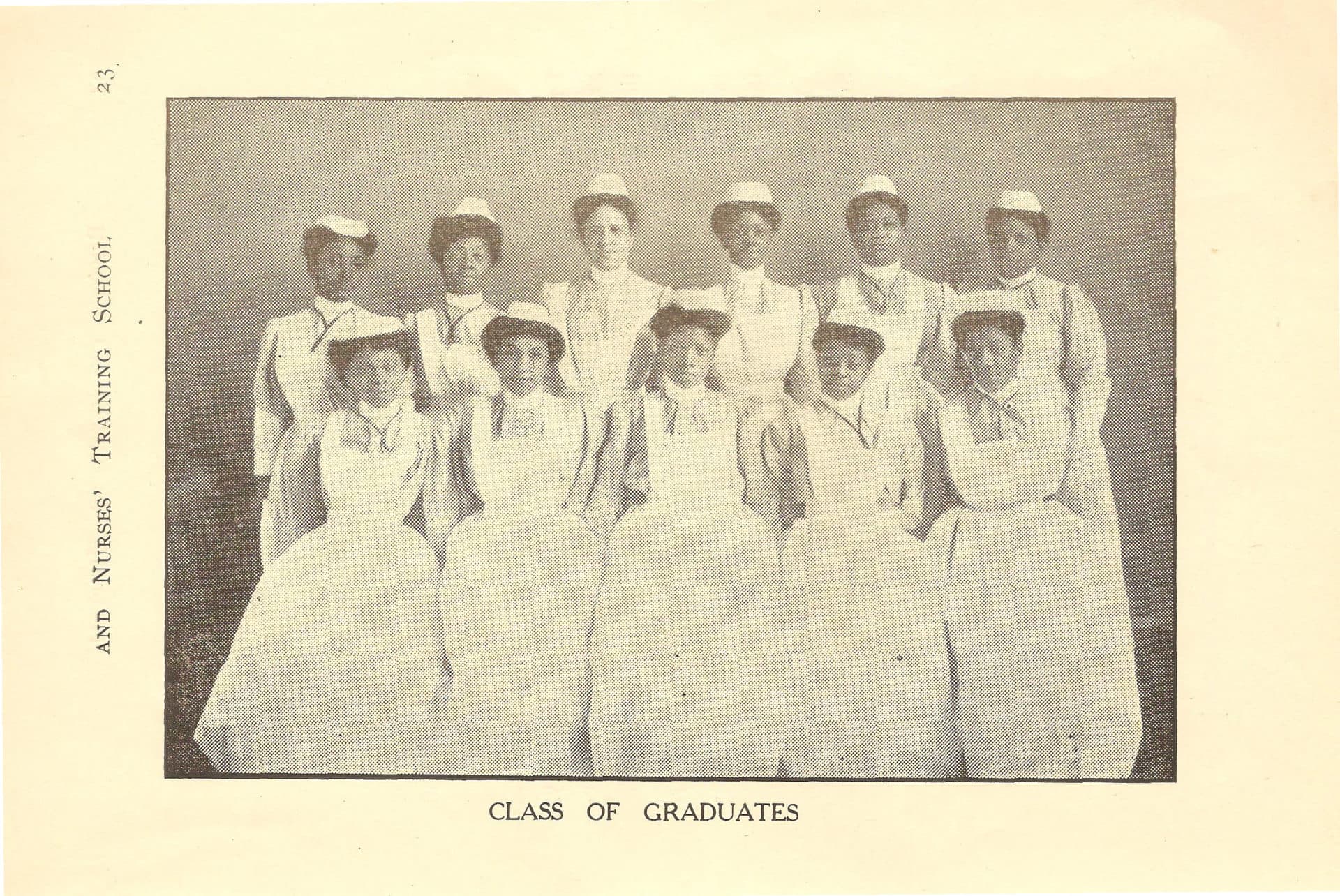

My research began with no goal other than to satisfy my own curiosity. What I learned is that Garland opened the hospital to provide access to care for anyone who needed it in the community, Black or not, rich or poor. He employed only Black physicians, only Black nurses, and established a training program for nurses who were otherwise denied admission to city hospital programs. He was a visionary.

Beyond those facts, little else is available online. I wanted to know more, so I visited the city archives and the public library. I contacted local historical societies. I interviewed professors who specialized in Black health care history. Each of them was fascinated by this seemingly uncovered history. I was too. And the more I learned, the more I wanted to tell Garland’s story.

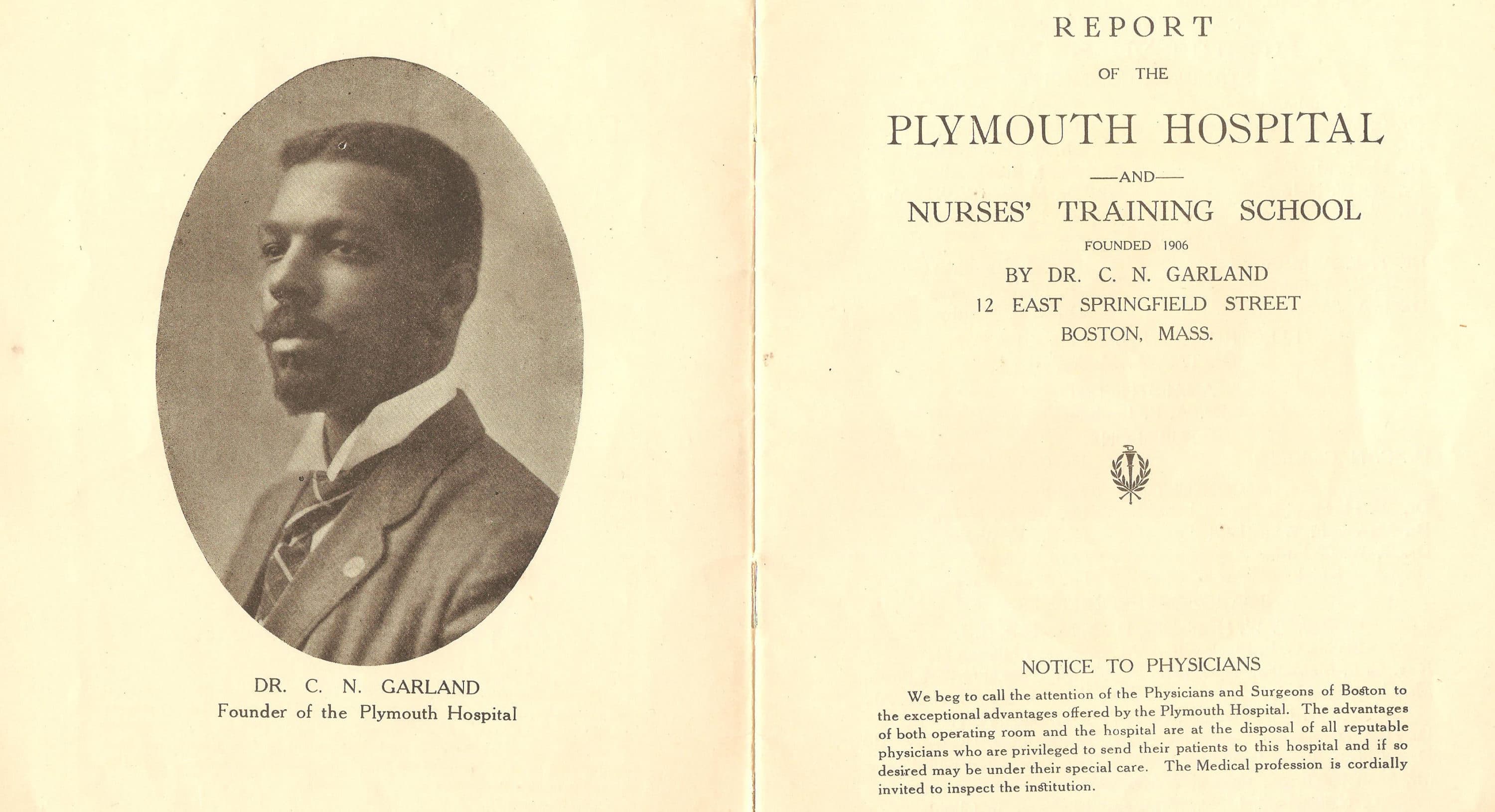

Then, a local South End historian shared a 20-page report that Dr. Garland issued in 1914 about the hospital. It included a letter from him to the community, an update on the nursing school, and a full list of medical cases and surgical operations. It also included photographs of the hospital rooms, including one of Garland sitting at his desk in his office.

There he sat, in my very apartment, over a century ago; the same fireplace, just to the left.

This breakthrough was exhilarating. Then I had another: I came across an article that included a quote from Dan Reppert, Garland’s great-grandson. Surprising myself, I looked him up on Facebook, and I sent him a message. I told him I lived in the building where Plymouth had been, and that I was working on a writing project about Garland. What a long shot, I thought. If he even replies, wouldn’t it be with skepticism? But Dan wrote back almost immediately. He wanted to talk on the phone, and we did. For an hour.

We just want his story to be told, Dan said. He sent me some absolute gems, true family heirloom documents: a photograph of a horse-drawn buggy ambulance in front of my apartment building; a handwritten memoir from Thelma, Garland’s daughter, about being the daughter of a Black doctor; even Garland’s invitation to meet the Queen of England.

You should talk to my mom, he told me; she remembers her grandparents very well.

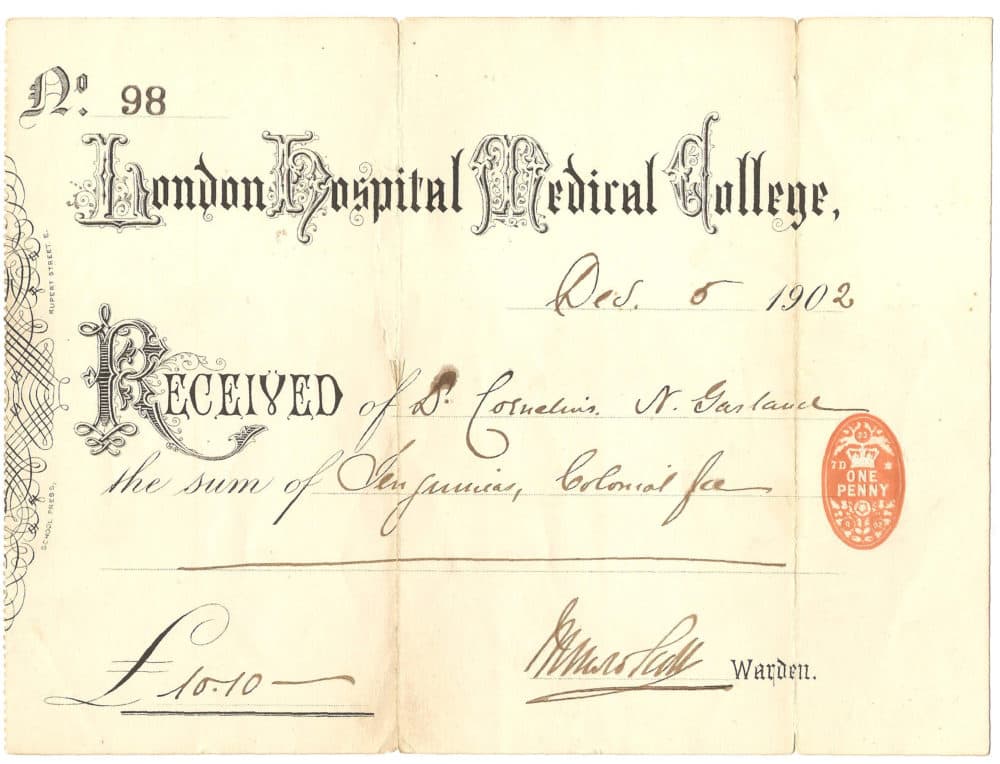

Garland’s granddaughter, Joan, was practically a celebrity from my standpoint. From her, I learned that Garland was the youngest of 12 children. His father was a carpenter who had a big business making and selling coffins, and they moved a lot. And, it meant a lot to Garland, Joan told me, that he had received financial help for his schooling from a white family that employed him, the McCrossins.

After Garland graduated from college, Mr. McCrossin wrote him a letter:

“It fills my heart with pride to see that my advice has been kept by you…I trust and predict that you will be able, as a man of the world, to distinguish yourself among man-kind and do good for the race to which you have been born, there-by setting a fair example to the countless millions of your people.”

The letter reflects the embedded racism inherent to the time, but suggests a deep respect for Garland. After all, he kept the letter — it was one of the items Dan scanned and sent to me — and he did become a leader in his community.

When Garland moved to Boston in 1903, he would have known that he’d be barred from practicing at city hospitals due to his race. As this was standard, and expected — and other hospitals like Plymouth already existed elsewhere in the U.S. — maybe it was always his plan to open his own hospital. City hospitals would not hire Black physicians, and Black women were denied admission to city nursing programs.

Garland recognized a way to offer opportunities to and elevate the skills of professional Black physicians and nurses. And at this time in the early 1900s, when racism persisted legally and without constraint, a person could go to Plymouth Hospital for any ailment, and if they couldn’t pay, they didn’t have to. In 1914 alone 800 patients received free care, all thanks to Dr. Garland.

Garland’s prescience didn’t end there. During a time when it was difficult for Black physicians to specialize in medicine, he obtained one in operative care and women’s diseases. This probably explains why Plymouth treated more female patients than male.

Over 20 years, from 1910-1930, Boston’s Black population grew steadily, with Plymouth Hospital no doubt contributing to the health of the city’s Black community. Garland was able to establish a private practice — as were several of the Black physicians who interned or trained at Plymouth.

In uncovering all of this, I felt I’d come to know Dr. Garland, in a sense, that the building where I lived was somehow protected by his good intentions, and that the neighborhood was bolstered by his care. I could almost see him tipping his hat to passersby, the very people whose health may have been in his hands, who may have gone to him knowing he wouldn’t turn them away.

Joan confirmed this. She told me, “He was very dignified, a rather handsome man. I would walk down the street with grandfather and people would bow to him. He treated many people for free; grandmother might have not wanted him to, but he never boasted about what he did.”

By 1928, Garland wanted to expand and open a second hospital. The majority of the Black community supported it enthusiastically. But Garland had one serious opponent, an influential civil rights activist, and owner of the Boston Guardian, the city’s Black newspaper: William Monroe Trotter. Trotter believed a second Black-only hospital would perpetuate existing racial problems. Instead, he vehemently advocated to integrate city hospitals, starting with Boston City Hospital.

This story, too, is fascinating: it includes Trotter writing letters to the BCH administration to convince them to admit two Black applicants to its nursing school. This, they believed, would set a precedent: if they admitted Black students to the nursing program, permitting Black physicians to practice there wouldn’t be far off.

Meanwhile, a feud played out in local headlines: a second Black hospital, or desegregate the city’s largest? In reality, Garland recognized that he and Trotter had a similar goal: equity for the Black community. He even lobbied alongside Trotter to have the students admitted, perhaps believing both plans could work in tandem.

After nearly a year’s effort, in 1929, Trotter’s plan succeeded. The students were admitted. Yet, it would take 20 more years until BCH appointed the first Black physician to staff.

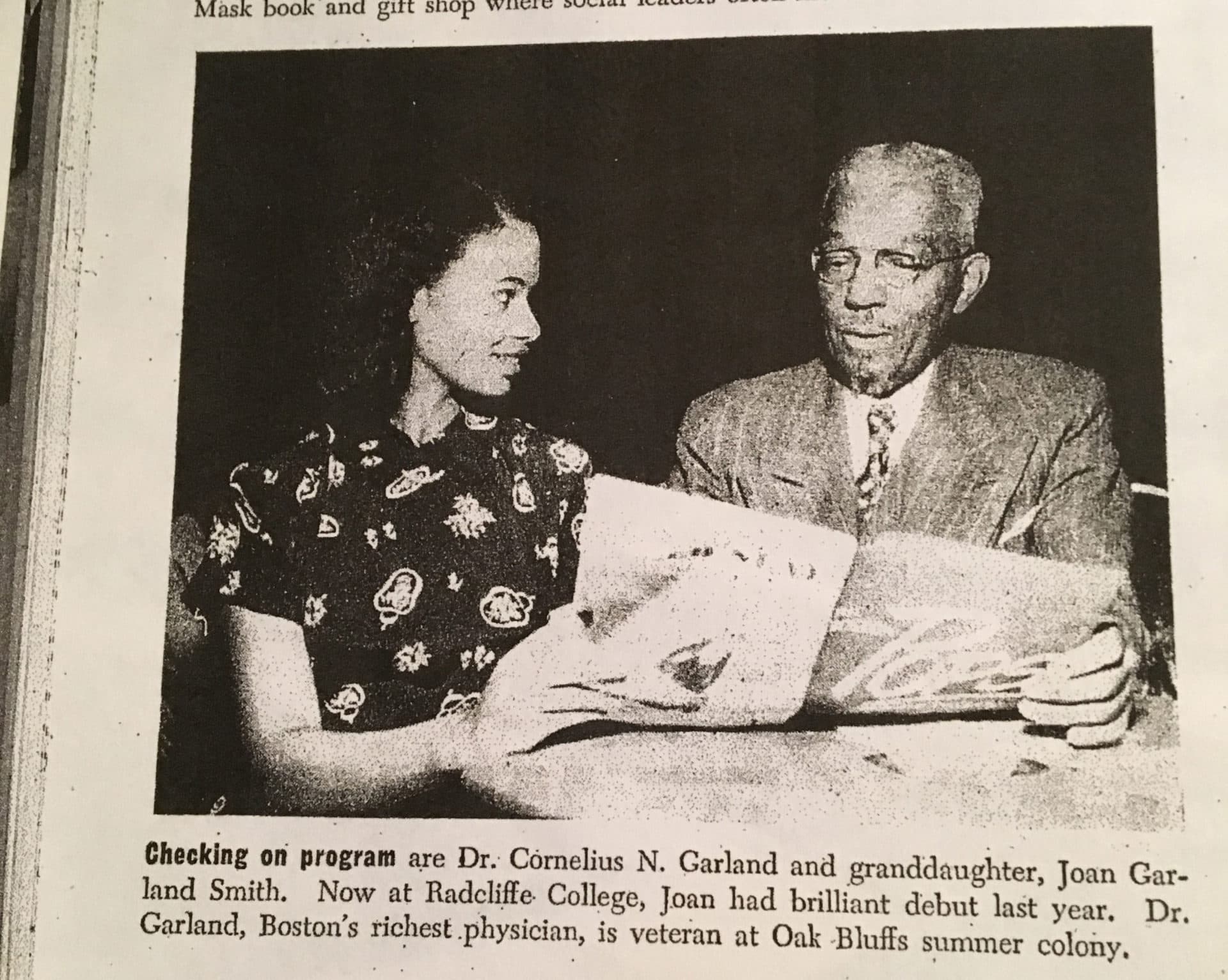

Garland closed Plymouth, but continued to thrive. His private practice remained popular. With his wife Margaret and daughter Thelma (Joan’s mother), he moved from the South End to Brookline, and became one of the first settlers in Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard, where he summered every year. Ebony Magazine ran a photo of him with Joan in 1949, calling him Boston’s richest physician.

Now, few know his name, much less his decades-long impact on the health of Boston’s South End community. More and more, we are learning how much medical training is taught through a biased white lens, and how much damage that incurs. Today, only about 5% of American physicians are Black or African American. How devastating that we’re still fighting the same battle, 100 years later.

Garland's legacy is an important piece of history that deserves more than a plaque. The hospital was called Plymouth. Its founder was Dr. Cornelius Garland.

Author’s note: Joan Reppert passed away on January 9, 2023, at the age of 91. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to know her and learn from her.