Advertisement

Commentary

How we can make traffic stops safer for people with autism

My 25-year-old son, Sam, has autism. Like many people with autism, Sam doesn’t have any physical characteristics that let other people know he has significant neurological differences.

Strangers periodically misinterpret his actions as being rude or even threatening because he often doesn’t understand social cues or personal space. For instance, Sam loves to ask everyone he meets when their birthday is, and he particularly enjoys meeting police officers. Officers are understandably suspicious when they see a young adult running towards them, greeting them with, “When’s your birthday?” It sometimes takes people a minute or two of interacting with Sam to realize that he has a disability and is simply a sweet, quirky, naive young man.

Sam received his driver’s license in September 2016, just after he turned 18. He’s an excellent driver and in seven years on the road, he’s never received a ticket. Like many people with autism, he loves to follow rules. He won’t speed or recklessly change lanes to pass other cars, or get distracted fiddling with the car radio, like many neurotypical people his age might do. He also always puts his cell phone on “Do Not Disturb” before starting the car.

But if a police officer pulled Sam over or responded to the scene of an accident, Sam might panic and become unable to follow basic verbal directions. Adding to the potential confusion, Sam’s speech is garbled — to the uninformed ear, he can sound intoxicated — and his lack of consistent eye contact (a hallmark of autism) could be interpreted as him being evasive or feeling guilty.

But if a police officer pulled Sam over or responded to the scene of an accident, he might panic and become unable to follow basic verbal directions.

If an officer followed the normal protocol of using a strict authoritarian tone and getting into his personal space, Sam’s anxiety about what was happening could escalate and lead to a police officer using physical force — and a potentially disastrous outcome.

It doesn’t need to be this way.

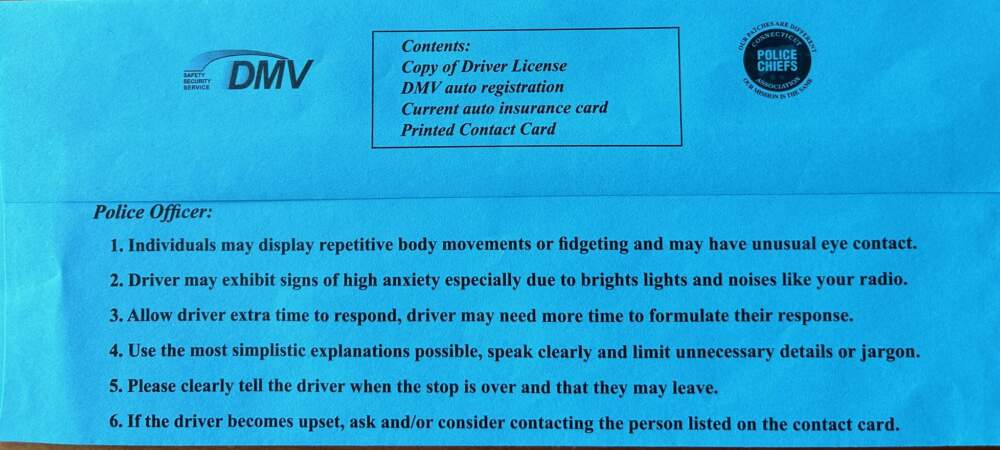

The “Blue Envelope Bill,” currently before our Legislature’s Senate Ways and Means committee, could make these potentially disastrous encounters far less likely. The bill would allow a driver with an autism diagnosis to request a blue envelope — which could be attached to the driver’s-side sun visor — to alert law enforcement of the driver’s diagnosis in case of a traffic stop or accident. These blue envelopes could help to avoid potentially tragic misunderstandings at minimal cost.

The bill has the support of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association, the State Police Association of Massachusetts Troopers, the Massachusetts Police Association and the Municipal Police Training Institute. The legislation under consideration is modeled after a law Connecticut implemented in 2020, at the urging of the Connecticut Police Chiefs Association.

This would affect more individuals and families than you might think. About one in 36 children in the United States is estimated to have autism. And there’s a troubling connection between people with an intellectual, developmental and/or psychiatric disability (including autism) and police violence. For example, a 2016 study (that looked at data from 2013 to 2015) found that disabled individuals make up one-third to one-half of all police shooting victims. Time reported in 2020 that “there is no reliable national database tracking how many people with disabilities, or who are experiencing episodes of mental illness, are shot by police each year” (the topic for another essay) but it seems likely that disabled individuals who are also Black have an even higher likelihood of being the target of police violence.

When Sam answers even simple questions with strangers, he — like many people with autism — often just parrots back the last thing that is said to him (it’s called echolalia), because it’s the easiest thing for someone with a communication disorder to do. However, it can be completely inaccurate. It reminds me of Matthew Rushin, a Black autistic young man, who spent 27 months in prison before Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam granted him a conditional pardon in March 2021. Apparently, Gov. Northam granted the pardon because he realized that law enforcement had tragically misinterpreted Matthew’s autism, echolalia and other health impairments.

If Sam were pulled over for a traffic violation, the best way for law enforcement, or any authority figure, to gain control of the situation would be to gently encourage Sam to take a minute to breathe deeply and reassure him that everything was going to be all right. The Blue Envelope Bill would make it more likely that this is how the scenario would play out. An officer would immediately see from the blue envelope that Sam has autism, and could read the typed guidance — on the envelope — about how to most effectively interact and communicate with Sam. At the same time, Sam could read the envelope’s guidance to remind himself what to do during the traffic stop.

The Blue Envelope Bill would be a game changer for Sam, and for our family’s peace of mind. It’s a simple, low-cost solution that would significantly benefit autistic drivers, the police officers who serve our communities and the general public.