Advertisement

As Told To

What I didn’t have to think about at a historically Black college

Editor’s note: Nadia Harden is the chief of staff and program director for the New Commonwealth Fund (NCF), a Boston-based philanthropy that supports Black, Latino and Indigenous entrepreneurs, innovators and nonprofits.

Cog interviewed Harden about her experience at Spelman College, one of 100 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), which are honored every September. Harden grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, where talk around her family's dinner table frequently turned to Malcolm X, Angela Davis and W.E.B. Du Bois. “I grew up in a household that really emphasized Black liberation, centered around the idea that collaboration and working within existing structures and systems is necessary at times, but that as Black people, 90% of the time, we hold the keys to our own success,” she said. “I think my decision to go to Spelman kind of naturally flowed into that.”

Here she is, in her own words, edited for length and clarity. — Cloe Axelson

I initially did not apply to any Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) when I submitted my first round of college applications. I think that was primarily the result of the fact that I spent most of my academic career in private schools in the Washington D.C. area, where, nine times out of 10, I was the only Black student in a class, and HBCU’s were not a part of conversations with my classmates.

I went to a highly competitive high school that almost did the college application process for you. Initially, I got really wrapped up in the idea that I wanted to go to a big state school or a school with a sports culture, but I realized about halfway through the application process that that environment wasn’t really aligned with who I was. I realized that I didn’t want to repeat high school — to continue to put myself in institutions that were really academically rigorous, but not designed for me culturally.

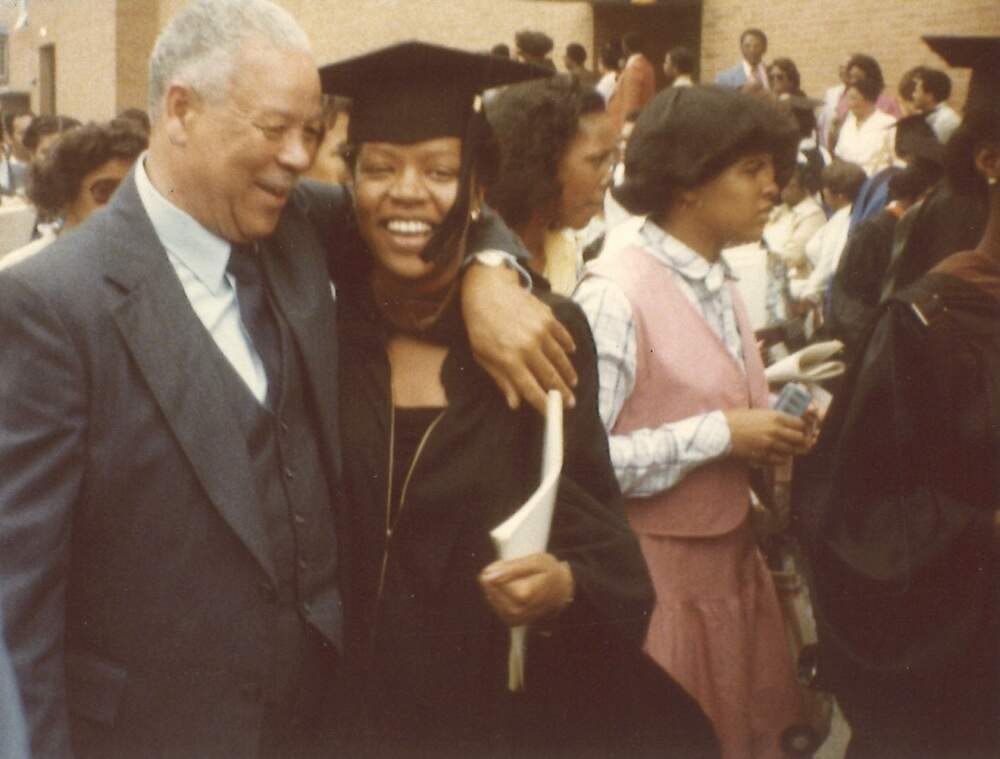

So, choosing to apply to Spelman, a school that would meet my academic and cultural needs, was really a last-minute decision I made with my parents, outside of my high schools extremely structured application system. I said, “Hey Dad, you know, this is the choice I want to make,” and he was fully supportive. Also, a lot of my family members and some of the most influential people in my life, attended HBCUs -- Howard, Hampton, Virginia Union — so there’s a long history there. But ultimately the catalyst for me was that I needed to take some agency over shaping what the next phase of my life was going to look like.

And truthfully, there were a couple of instances that pushed me over the edge in high school and helped me realize that a similar academic environment wasn’t going to serve me. I just knew I didn’t want to have to fight every day.

I was taking an AP government class, junior year, I think. I don’t remember exactly what the assignment was, but for some reason, we were creating campaign collateral, and I created these Obama stickers. My dad's been involved in politics my entire life. I worked on campaigns, I’ve worked the conventions, and because of that I felt connected and excited about the project so, I created these stickers and part of the assignment was to pass them out. A classmate took what I created, ripped it up, shredded it in front of my face, and said, “You're only doing this because he's Black and you're Black, too.”

That kind of attitude continued during the conversation in our AP government class around race and politics. And honestly, I was just really sick of having the conversation — of being in an environment where that’s where every conversation always started.

I think one of the beauties of Spelman and HBCUs in general, is that you get to have more nuanced conversations around things like politics. We’re not talking about “is it because he's Black or not,” we're talking about what Obama’s actual policies are, and what stances he’s taking on issues. The Blackness isn't the first thing everybody sees, because it’s something we all have in common.

The Blackness isn't the first thing everybody sees, because it’s something we all have in common.

I hope people are starting to see, now more than ever, why HBCUs were created in the first place — and why they’re still necessary today. Remember, HBCUs were created to provide and unlock resources to meet a need that was not being met. That looked a lot different in 1881 when Spelman was founded, but the needs of Black students are still not being met by predominantly white institutions, and we can see based on increased enrollment over the last several years that students are continuing to look to HBCUs.

And it’s quite evident by the caliber of students HBCUs produce, that they are a necessary part of the fabric of this country. We’ve all seen the statistics: something like 40% of all Black engineers, 50% of all Black lawyers, 70% of Black doctors are graduates of HBCUs. There is a need for HBCUs to produce Black leaders — and not just for Black communities, right? The world needs them.

To me, HBCUs are a proof point for what can happen when Black people have equal access to resources and education. I think we’re doing something like this at the New Commonwealth Fund on a smaller scale: investing in Black leaders and providing them with a culturally relevant experience.

I think as a Black woman moving through the world, there are certain times and instances when things happen, and I have to pause and question whether or not my interaction with somebody and how they treated me was connected to the fact that I'm Black. But I did not have to consider that when I was at Spelman. That was not — it could not — be a factor. And not having to spend energy unconsciously processing every interaction with somebody unlocked for me the ability to engage in my schoolwork in a different way, quite frankly.

Because I went to Spelman, I think I am much better equipped to walk into any room of people who may have preconceived notions about who I am, and feel confident about what I have to offer, and say the things that not everybody wants to say.

Spelman was the best four years of my life — without a doubt. I didn't have to spend those really formative four years of my life trying to assimilate and silence myself and put myself in a box. I think it has been the only time where I didn't have to consider the fact that my Blackness might be a barrier, but rather it was something that I was taught to celebrate and lean into. That was not at all the first time I’d experienced that, but I got to live it for four years.