Advertisement

Commentary

I’d like to apologize to my Barbie

It was Barbie season recently, and everyone had a story to tell. Mine, sadly, reminds me of my worst moments as a daughter, proof that I was a disobedient, intractable, ungrateful child.

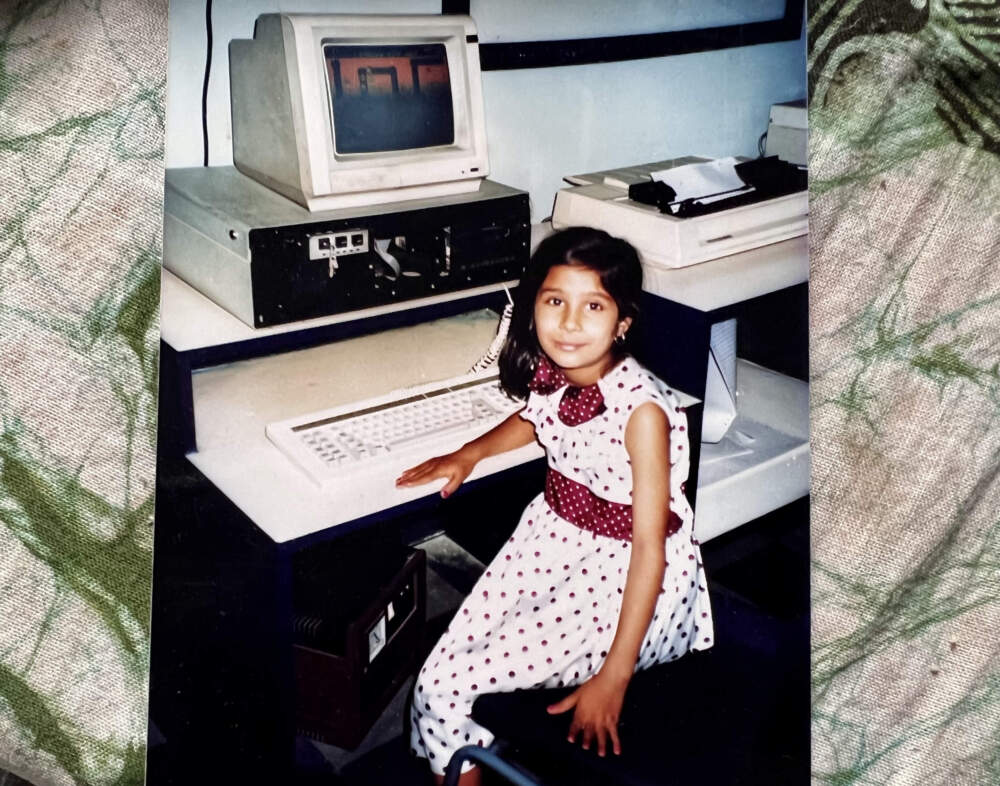

But I can’t take all the blame. It was the mid-90s, a culturally boring decade — my dad was still replaying Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water” and Michael Jackson's “Bad” on cassette tapes — and I was a rebellious girl growing up in small-town India.

I had no friends. The neighborhood girls, according to my parents, were bad. They belonged to an entirely different socioeconomic stratum and I wasn’t allowed to mix with the rich girls.

My parents, with their teachers’ salaries, could afford only to rent, but the neighborhood girls’ parents owned cars and lived in homes with tall white gates, bougainvillea pouring onto white walls. Their vast incomes allowed them several sets of school uniforms, an unlimited budget for firecrackers, extravagances I could only dream about. The neighbor girls’ biggest flaw: They played with Barbies from America.

The Barbie was no ordinary doll: She wasn’t as big as a baby, hollow as a boat, like my doll. Barbie was fully adult, with breasts and blond hair. She wore lipstick and she looked like she’d been to places and was on her way to more. She was three different types of plastic: her legs were supple and her knees bent. Her arms were stiff and solid, but her face contorted when pressed. Just like us, Barbie was flexible in some places, rigid in others.

She wore lipstick and she looked like she’d been to places and was on her way to more.

One summer afternoon, sitting in the air-conditioned bedroom of one of the rich girls, I realized that Barbie wasn’t just an embodiment of the rich girls’ fantasies, but a projection of what was possible for them, 20, even 10, years from now.

My parents were right — I oughtn’t have aspired to the rich girls’ Barbies. Just getting invited to their homes and holding their dolls came at a cost. I had to complete their math homework, lie to their mothers about their whereabouts. I had to become a task rabbit. One afternoon, I hand-delivered party invites to 20 households in the neighborhood, helped the cook transport tubs of ice, snacks and crates of Coca-Cola to our landlady’s garden, helped festoon sparkles over perennials and fruit trees.

That night, uninvited to the party I helped plan, I sat in our studio apartment listening to party revelers dancing and chatting in our landlady’s garden. I decided: no more servitude. It was time to ask for my very own Barbie. I begged and begged my parents. I let them cheat me out of a whole year of Sundays, committing each to a house chore or studying. I promised them things I knew I could never deliver: a 100/100 in math and physics.

My mom called her sister, and a month later, my aunt came for a visit, a Barbie doll in tow. I still remember shrieking at the sight of the hot pink package. This was no ordinary Barbie. She was Teacher Barbie. She wore a snug black jacket and a black pencil skirt, and she came with a change of clothes (a hot-pink bathing suit), a notebook and a blackboard, which she held in her hands.

Just getting invited to their homes and holding their dolls came at a cost.

But the rich girls took one look at my Barbie and pronounced her unfit. The reason: her strange, bent arms. The other Barbies’ arms hung nonchalantly by their sides, like they’d just been shopping and unloaded their purchases. Once the little blackboard was taken away from my Barbie’s hands, she looked silly, like someone awaiting a package. Or holding an imaginary partner at a dance, alone and forlorn.

“Why does she have a blackboard?” a rich girl asked.

“Like Shilpi’s mom, she has a teaching job,” replied another, laughing.

My Barbie was Working-class Barbie. She could never kick back and lean idly on chairs like the others.

I ran home in tears. A few weeks later, I put the blackboard inside Teacher Barbie’s hands, pushed her back inside her box. The next day, my mom delivered her to the children who lived by the railway station.

Every time I think of my first (and last) Barbie, I am filled with shame. Why couldn’t my aunt have bought me an ordinary Barbie? It occurs to me only now: possibly, my aunt saw an affinity with Teacher Barbie. She was supposed to instill in me an appreciation for educators.

But at the time, she taught me to fear being different. For my teenage years and much of my 20s, Teacher Barbie made me think that being open, expecting love, was naive.

I now know that Barbie wasn’t at fault. It was the girls who were cruel. Teacher Barbie just needed to find her tribe, the people who accepted her. I want to find my old doll and apologize. I'd like to tell her that I'm sorry I didn't stand up for her. In a room full of the commonplace, she was different: independent, hardworking and extraordinary.