Advertisement

Commentary

Do we ever really know our parents?

In my 40 years as a reporter and editor, I have asked questions of all kinds of people: governors, city councilors, farmers, fire fighters, fishermen, senators, men in prison, women in domestic violence shelters.

But the one person I want to question the most has been dead for almost 50 years.

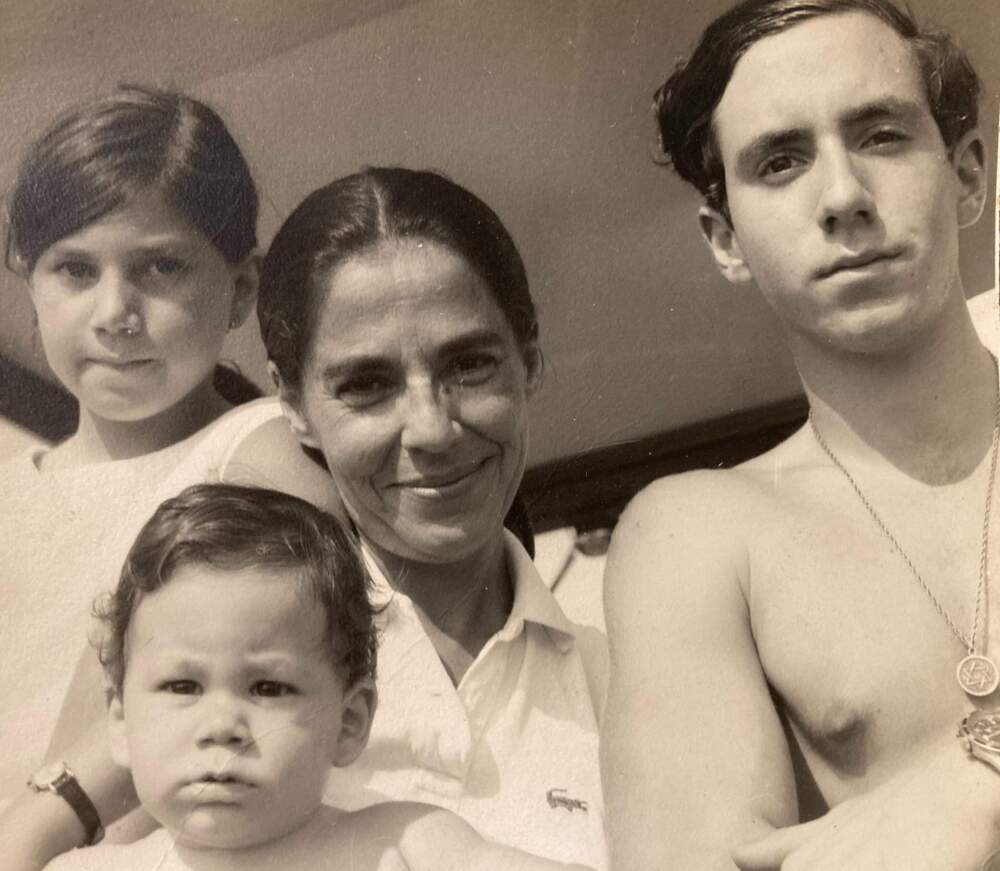

October, the month of ghosts, skeletons and witches, is now gone. But I still have a ghost in my life: my mother, Harriet Natalie Brodie Arbib Schalit. She died at Yale-New Haven Hospital in 1975, a month after her 50th birthday and two weeks before I turned 18. My older brother was 21 when she died, and my little brother was eight.

I've been thinking a lot recently about how strange it is never to have known a parent while you are also an adult, as my grown children know me. All my understanding of my mother comes from the ever-more-distant place of knowing her as a child.

When I think about her now, she’s not dead. She’s alive, sitting at the kitchen table — a Saarinen tulip table (she had expensive taste) — smoking a stubby, unfiltered French cigarette and drinking an espresso. She’s laughing, because she laughed a lot, a deep-rooted chortling that started in her belly and emerged finally as a juicy cackle that crinkled up her whole face.

All my understanding of my mother comes from the ever-more-distant place of knowing her as a child.

That was the good version of my mother, the mother who read two New York newspapers every day and always did the crossword puzzles, including on Sunday. She was the one who would drive 10 miles from our Connecticut home to get “the best butter-and-sugar corn;” the one who let me stay home from school so I could read books, because she was a Greenwich Village progressive school graduate and didn’t think much of my suburban teachers or their educational philosophies. This version of my mom played boogie woogie piano, and hated Richard Nixon.

But this type — a bohemian New York Jewish intellectual, a literature and music lover and an artist — was not all of her.

In 1945, she lost her first husband, a war hero. Soon after, her beloved sister died. And that’s when I was told the bad version of my mother emerged.

This version of my mother drank and took pills. For weeks on end, the woman sitting across from me at that Saarinen table had blank, drooping eyes, slurred her words and let those French cigarettes smolder until they were almost two inches of ash, threatening to fall and ignite our home and our lives. My father — a violent man — was largely absent, so I spent much of my childhood putting out the little fires my mother caused, putting my stumbling mom to bed, and hiding the car keys.

Advertisement

Children don’t know why adults do what they do, except perhaps in the grossest terms. So my description of my mother during what other people would call binges, was that she was “sleepy.” Only later, as a teenager, would I rifle through her dresser or her purse, find pills and flush them down the toilet. Only later would I dump the liquor bottles down the drain.

But as anyone who knows addicts knows, those things don’t work. And they can make the very people who are supposed to love you hate you — at least momentarily. My mother wasn’t nice when I took away her pills and her liquor.

I've always felt regret that I never got to ask my mother the kind of questions I would have known to ask when I was a grownup — personal ones, like why did you marry Dad and stay with him? Why didn't you go to college? Was your life more about disappointment than happiness? Why did you check out when we needed you? Why didn’t you love us enough to be there? And the hardest one of all: Who are you, really?

I thought for decades that I was alone and isolated in the feelings behind those questions. When a parent dies, especially if you’re young, you feel like you’re the only person in the world to have experienced that loss. You’re marked by it, and it takes years to not think about it every day. But that sense left me long ago, replaced by this desire for answers.

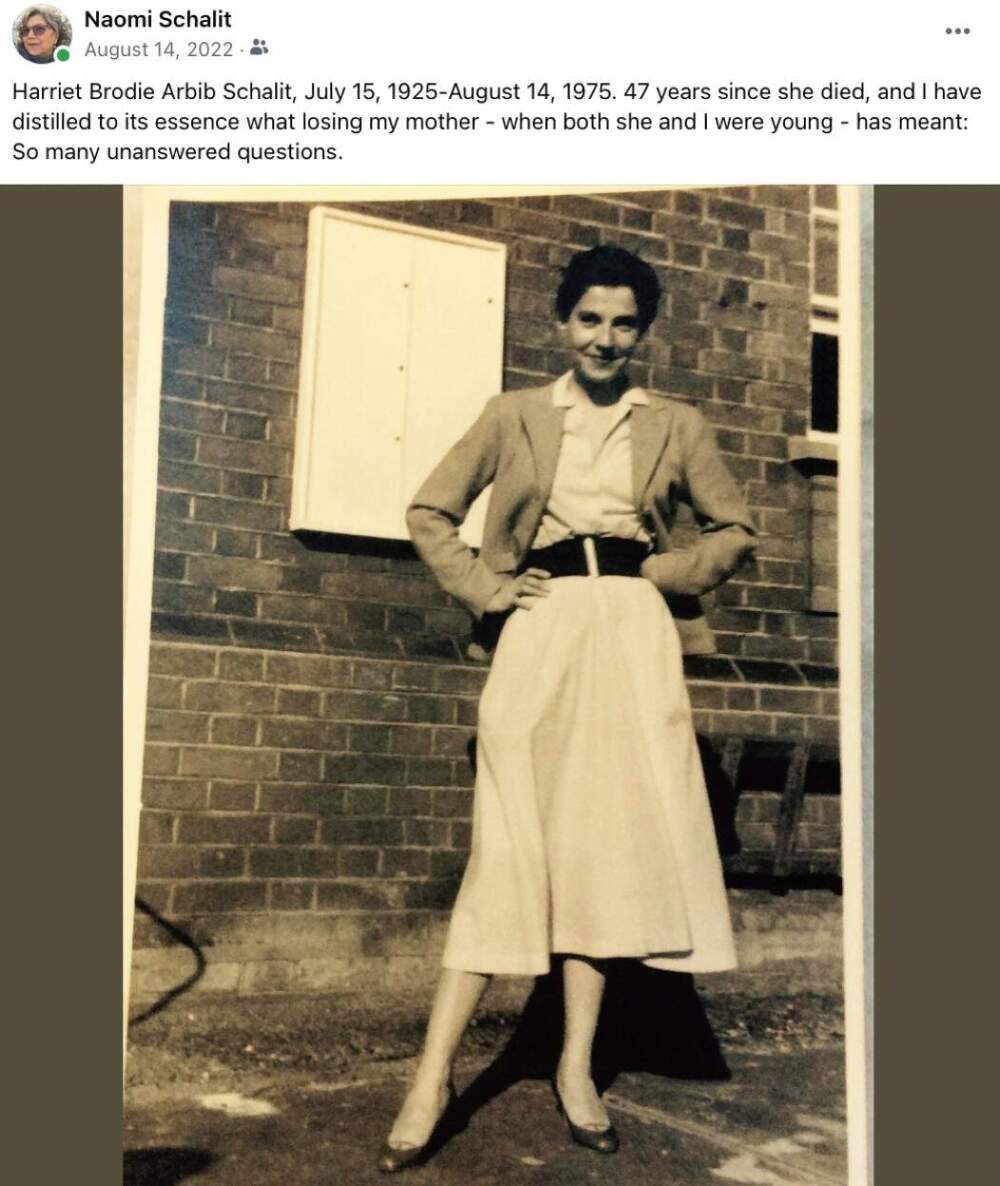

I wrote once on Facebook about that yearning, on my mother’s Yahrzeit — the anniversary of her death — when I usually post a photo of her: “Harriet Brodie Arbib Schalit, July 15, 1925 — August 14, 1975. 47 years since she died, and I have distilled to its essence what losing my mother — when both she and I were young — has meant: So many unanswered questions.”

And that’s where a startling answer showed up.

“Even if your mother lives to be very old — as mine did — there are still unanswered questions,” wrote a friend. “Maybe unanswered questions are what parents leave as inheritance.”

Questions have long animated my life. My work as a journalist is to ask them and get the answers. I love hunting for answers, especially when people won’t give them to me.

But I cannot get answers from a ghost. For nearly five decades, I had hungered for my mother’s answers. Yet on that August day, that had so long represented grief and longing to me, my friend’s simple reply on Facebook put my questions to rest.

There would always be unanswered questions, I realized. But they were only a part of my inheritance. The rest — as all children whose parents have died know — included my memories, especially one beloved memory: My good mother, laughing at the kitchen table.

That will have to be enough.