Advertisement

Commentary

Not all monsters look like monsters

The rape trial that shocked France and renewed calls for a reckoning with rape culture has concluded. Gisèle Pelicot’s now ex-husband, Dominique, 72, was convicted in Avignon, France, of repeatedly drugging and raping her. He was also charged with inviting at least 72 other men into their home between July 2011 and October 2020 to rape Gisèle while she was unconscious.

Dominique received a 20-year sentence, the maximum allowed by French law, and will not appeal, according to his lawyer. He admitted to drugging and raping Gisele two or three times every week and to inviting men to their home to rape his wife. Fifty men stood trial with Pelicot. All were convicted, but their sentences differed and several have indicated their intention to appeal their sentences.

Pelicot would likely have continued the abuse if a woman did not report him in 2020 for taking “upskirting” photos in a supermarket. The police seized his phone and computer which contained more than 20,000 images and videos Pelicot had taken of the rapes of his wife he orchestrated.

The revelation of his crimes reverberated across France and beyond. Not a single one of the men who entered the Pelicot’s home where they found Gisèle unconscious — and offered up in her own bed for rape — called the police. Nor did any of the men who connected online with Pelicot in chat rooms (that host something like a rape marketplace) stand out in their communities as dangerous. Instead, as much was made of in the press, they included a soldier, a nurse, a journalist, a prison warden, a volunteer fire fighter, a carpenter and a neighbor. They took on the group identity of “Mr. Everyman.” Pelicot himself was described by Gisèle as “un super-mec,” a great guy, a loving husband, father and grandfather.

Not a single one of the men who entered the Pelicot’s home where they found Gisèle unconscious — and offered up in her own bed for rape — called the police.

The trial spotlights the grim reality that not all monsters look like monsters. This is one key feature of rape culture: how ordinary many of the men who rape are. We cannot understand this case without confronting the disturbing reality that the men who raped Gisèle went about their lives without suspicion. One of them even regularly exchanged greetings with her at the local bakery.

As a recent U.N. study documents, girls and women are most at risk of sexual violence from the men who live in or have access to their homes. The World Health Organization in 2021 described sexual violence as “devastatingly pervasive,” with 1 in 3 of all women harmed, and young women targeted especially. Although studies like these expose the pervasiveness of sexual violence and the ordinary men who perpetrate it, the myth persists that rapists do not look like the decent men they coexist with.

The Jekyll/Hyde framing of Monster of Avignon/Mr. Everyman emerged at trial as a way to shift blame solely to Pelicot. Many of the accused men blamed Pelicot for duping them. They said they were lured to the house with the offer of a threesome in which Ms. Pelicot would pretend to be asleep. Yet, as the videos show, her limbs were heavy and limp, and she could not be awakened. Their rationalization exposes the monstrosity of what rape culture helps ordinary men explain away. Together, these men enabled, committed and justified sexual violence. It took a village to rape Gisèle Pelicot.

Advertisement

Together, these men enabled, committed and justified sexual violence. It took a village to rape Gisèle Pelicot.

The use of anesthetics in the history of rape is surprisingly common. In many cases of sexual assault, the victim is asleep, drunk or drugged, in a coma, under anesthesia, or suffering from a head injury or other incapacitating condition. Unconscious people cannot consent, obviously. But because of the way many laws are written, rapists are able to use “unconsciousness” as a legal defense to create a gray area for consent.

I have written about how comedian Bill Cosby, for example, evaded responsibility for decades during which he drugged and sexually assaulted 60 women. He was finally sentenced in 2018, to between three and 10 years in prison for assaulting Andrea Constand in 2004 (his conviction was overturned on a technicality in 2021). In his deposition at her civil suit Cosby testified that he had drugged her without her knowledge and sexually assaulted her while she was unconscious:

“I don’t hear her say anything. And I don’t feel her say anything. And so I continue and I go into the area that is somewhere between permission and rejection. I am not stopped.”

Many rapists portray the absence of resistance as the presence of consent. Some of the men who raped Gisèle Pelicot defended their actions by saying they believed what Dominique Pelicot told them: that she was pretending to be asleep and therefore consenting.

The Pelicot case took place in France, where the lessons of the #MeToo movement have been slow to take hold. Yet a previous case paved the way for Giséle Pelicot’s courageous testimony and supports her hope that lasting change in law and rape culture is possible.

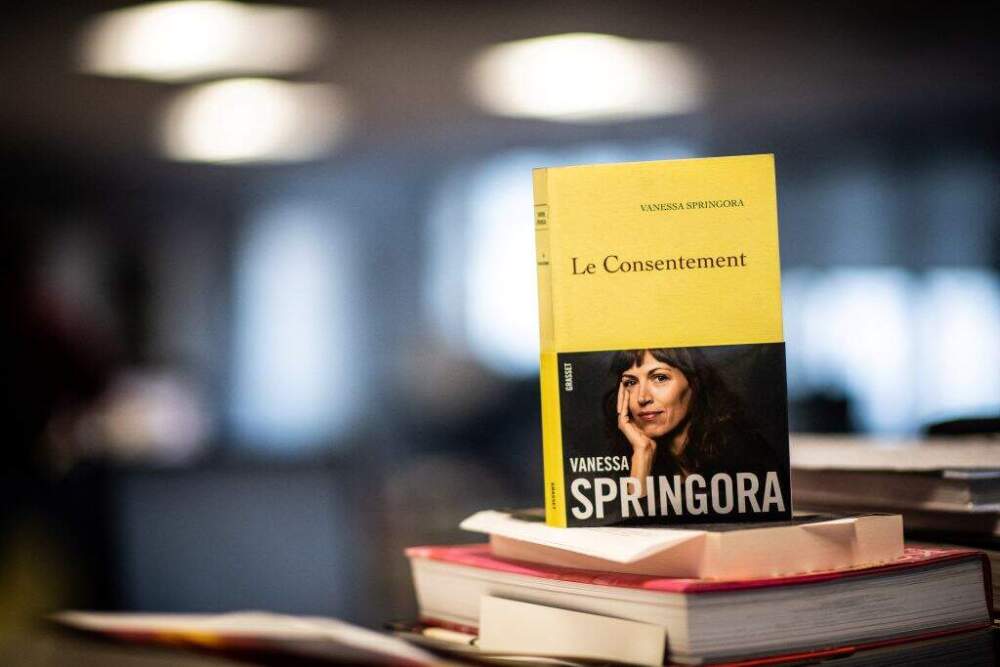

In 2020, “Consent,” a memoir by the French writer Vanessa Springora, propelled a reckoning with the sexual abuse of minors in France. When she was 13, Springora was groomed by 50-year-old author Gabriel Matzneff for a sexual relationship. None of Matzneff’s contemporaries nor Springora’s mother (the custodial parent) intervened.

Springora argued that consent is a meaningless term for a child who is coerced into sex with an adult. Until “Consent” was published, France had no age of consent law. Like Gisèle, Springora sought to change the law and the culture of consent to prevent sexual violence. Her memoir is credited with helping to pass France’s first age of consent law in 2021, which makes sex with someone under 15, rape — with a 5-year age gap exception — and punishable by a 20-year sentence.

Gisèle repeatedly sought help from doctors for symptoms related to her abuse. She was exhausted and slept most of the day. She had trouble with her memory and worried she had a brain tumor or Alzheimer’s. She had mysterious gynecological problems. Yet, when her adult children called, Dominique answered the phone and made excuses. He controlled Gisèle’s access to doctors and accompanied her to appointments where he learned information that enabled him to continue the abuse. Not a single doctor tested Gisèle for signs of drugging. No one questioned Dominique — the doting husband who shadowed his increasingly frail spouse.

Then 50 ordinary men who stood trial for raping Gisèle Pelicot used an alibi that’s built into rape culture. They offered this as their defense: Gisèle was Dominique’s wife, so he could do what he wanted with her; Gisèle was equally to blame as a willing partner in a sex ruse; Gisèle and Dominique were a normal couple, so nothing was amiss. The defense even sought to suppress the video evidence. They argued that the videos were too shocking and prejudicial to be shown in open court.

Gisèle Pelicot insisted that those videos be made public. She refused anonymity and, instead, attended court daily and testified. She wanted to raise awareness of “chemical submission,” so that “one morning, when a woman wakes up and can’t remember what she did the previous day, she will say to herself: ‘Well, I heard Mme. Pelicot’s testimony.’”

She hoped that by publicizing the everyday quality of the “macho and patriarchal culture” that enabled her victimization, things would change. Above all, she insisted that shame must change sides — and that’s what became a rallying cry across France.

In the face of ordinary monsters, Gisèle Pelicot showed extraordinary courage.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.