Advertisement

Commentary

My daughter knew that death is part of life

Perhaps it was due to living with illness, or simply because she was deeply in tune with the natural world, but my daughter Caitlin had an acceptance of death and its role in the wheel of life.

She loved birds, and had a special respect and affection for owls. Once, some kids at school told her that she looked like a barn owl, and it became a lifelong endearment. After her death at age 33 from complications of cystic fibrosis, the owl went on to symbolize her quiet wisdom. When the artist Kat David painted a beautiful homage to Caitlin, she included a barn owl.

On the day before the most recent anniversary of her death, her close friend Katie visited. She suggested a winter solstice remembrance ceremony at the cemetery where we are in the process of building a permanent, final resting place for Caitlin, a complicated project that has taken time. She planned to arrive at our house by mid-afternoon, so we could reach the cemetery before dusk. When she knocked on the door, there was a look of shock on her face. “Auntie Mare,” she said, “there’s a large owl sitting in the corner of your driveway.”

I had always wanted to see an owl, but if one was sitting unmoving in daylight, it had to be injured. I was afraid as I followed her outside.

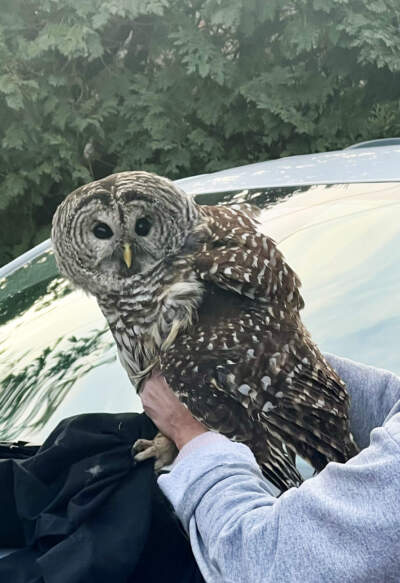

It was a beautiful barred owl, its feathers ruffling in the wind. It sat quietly in a corner of a stone wall. It did not try to move, even as we inched close enough to understand that its left wing was damaged. Its eyes followed us, almost as if it were asking for help.

Inside, we called mass.gov’s wildlife division. A woman explained we could let nature take its course or contact a permitted wildlife rehabilitator. She directed us to a list of names, and I began calling ones nearest to my town, leaving desperate voice messages.

These people are volunteers, and it was heartening how quickly they called back. The first woman couldn’t get to us but advised us to text a specific other woman, and to put a box over the owl to protect it if it tried to move. I texted the reference as another woman called back. She asked if I had a big net. No! My heart was already racing. I did not have a net! She began to explain how to use a towel and a shovel to get the bird into a box, so we could bring it to the Tufts School of Veterinary Medicine in central Massachusetts. I was listening but panicking, seriously doubting I could get an actual wild, injured animal into a box. At this point, Katie took the phone. She asked the woman to repeat the instructions.

Advertisement

She hung up. “We’re going to have to do this,” she said. Her calm gave me courage. I grabbed a towel. I ran up to the attic hoping to find a box large enough to hold an owl. But then––salvation––the third woman texted: I’m 20 minutes away.

We went back out to the driveway to wait for this angel volunteer. The owl had not moved. It watched us. It looked tired and kept closing its eyes. Nearly an hour had passed.

Those moments were emotional, and became more so when the volunteer, Julie, arrived with a helper. She slowly moved backwards towards the owl, holding a large black cloth. The owl never flinched. Indeed, it turned its head and watched her approach. When she covered him with the cloth, he collapsed. “Oh buddy,” she said. She hugged and rocked him. “I’m so sorry.”

She gathered him up, so kind and loving, and propped him against the hood of her car to remove the cloth. She had a strong hold on his feet as she inspected the damaged wing. At this point, the owl’s eyes were wide open, and as they latched on to me and Katie, he spread his one good wing. The magnificence and awe of that wing span as he tried to swoop toward us!

They were not going to be able to save him, Julie said, but the vets at Tufts would euthanize and bury him with dignity. She tucked him into the box she had brought: a veterinarian’s cat carrier.

It turns out that a large owl can easily fit into a small cat’s box, a fact that felt significant. Caitlin’s nickname had been Kitten, Kitty, Cat. Printed on the box were the words, “Cats are Angels with Whiskers.”

Julie drove off, and we got in my car. How did the owl come to be there, in that protected corner of our driveway? Why did it happen? What was the meaning of it? Was there meaning? We asked ourselves these questions as we drove to the cemetery.

It was close to dusk when we arrived at the gravesite-in-process: a large, stone dolmen that Caitlin’s father, my husband, Nick, is building.

Dolmens––think Stonehenge––date back to the Neolithic period. They resemble stone doorways and are often steeped in mystery. Caitlin’s dolmen consists of six nine-foot stone pillars that will support a flat, horizontal capstone. Nick calls her dolmen a “pass-through.” He says it represents how we pass through this physical life on our way to the spiritual.

Katie and I picked branches from evergreens and laid a circle of them on the ground beneath the pillars. We lit a candle. We talked about Caitlin, and the owl’s visit, and about how it has always felt fitting that Caitlin left during the winter solstice, a time for grieving and reflection, and waiting for the return of the sun.

Other bird deaths occurred that week among Caitlin’s loved ones. They are not my stories to tell, but these happenings—during the anniversary week, at the end of a hard year for so many—reminded us of the truth Caitlin seemed to grasp: that death is a part of life, and we need not fear what’s to come. The owl’s visit was, for me, a reminder to embrace this connection with nature and loved ones, to find calm in it, and to trust in life’s cycles, both in grief and in catharsis.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.