Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Harvard Immunologist: No Widespread Antibody Testing For Another Month, At Least

Resume

Nearly 95,000 Massachusetts residents have now been tested for COVID-19, but barriers to testing still exist.

Dr. Michael Mina, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard specializing in immunology and infectious diseases, joined WBUR's Morning Edition to discuss the continued bottleneck. He says that, although we are now approaching a near-surplus of actual coronavirus tests in Massachusetts, our ability to administer those tests is still inhibited, thanks in large part to a shortage of the single-use, plastic swabs used to collect the virus from a patient's nose.

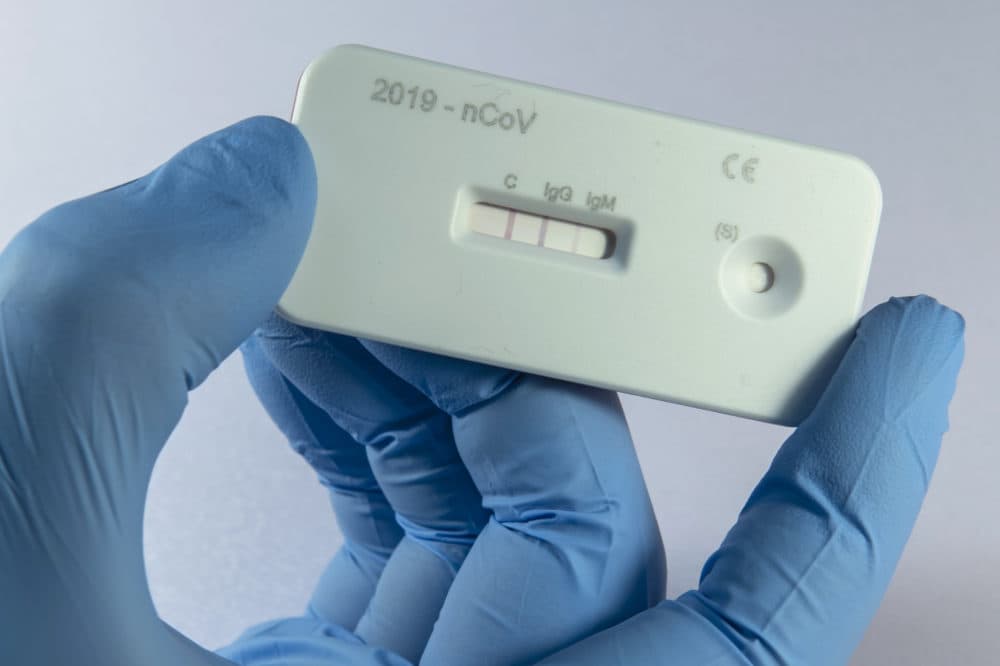

Another method of detection that will ramp up in the coming months: antibody testing, which looks for the presence of COVID-19-resistant cells in the bloodstream of a person who has had the disease and recovered from it. But Mina says this serological testing won't become widespread for another month or more.

Listen to the full interview or read highlights below.

Interview Highlights

On the shortage of nasal swabs

We finally got to a point where we actually have almost a surplus of the actual tests themselves, and now it's just getting the sample out of the person, and that requires a 25-cent piece of plastic that was made by a small number of manufacturers, which have actually been hit pretty hard by the coronavirus in their factories; and this has really created a dent in the global supply chain of these small swabs.

Many companies are now getting on board with trying to re-up their ability to produce these swabs in a higher throughput fashion. ... companies, like ThermoFisher based right here in Boston, and you even see biotech startup companies using 3D printers, trying to make some of these swabs.

On the two types of testing

For PCR testing, which is the type of testing we're doing to look for the virus in somebody's secretions or in their nose — we're still not there. We have really increased testing a lot over the last couple of weeks: we are up over 100,000 tests per day in the United States. But in reality, for a country the size of the United States, we really need to be quite a lot higher than that, and I don't know that it will necessarily get to where we absolutely need to be in terms of testing everyone for public health use.

But what we're seeing now is a shift towards what we call serological or antibody based testing, which is a whole different type of test using a blood sample. It looks for ... whether somebody has been exposed in the past to the virus. So this can also help offset the need for these viral tests (PCR tests), but I think we're looking at least at another month before we actually have any substantial amount of antibody testing being done across the United States.

On the prevalence of false negatives in testing

The test itself is actually very sensitive and very specific, meaning that if the virus makes its way into that test, it will be picked up for the most part. Where the problem comes in with false negatives is actually the swabbing of the person's nose, and there we see anywhere from a 10-15% loss in terms of actually detecting virus.

The good thing is that there is not as much variability for people who have a lot of virus in their noses. If you stick a swab into somebody's nose and they have millions of viruses in their nose, you're probably going to be able to detect them without a problem. And these are the people who are most concerned about transmitting to other people.

So the false negatives become a real issue if we're using it to know if somebody has recently gotten over the infection and we're looking for really small numbers of viruses — then the swab can sometimes miss them.

On a possible timeline for a vaccine

Phase 1 trials have actually started, which is amazing; it's really very, very fast to get a Phase 1 trial of a vaccine going. But this is just a safety trial. This doesn't get at how well the vaccine works, it is designed to make sure that the vaccine is safe to give to people. So the real hard part of the vaccine trials are going to come next, which is trying to see how well they actually work to protect the individual from infection. That will be a longer type of study and maybe we'll have a vaccine, you know, early in the new year.

This segment aired on April 10, 2020.