Advertisement

Why A Federal Order In The Weymouth Compressor Case Has The Natural Gas World Worried

In the six years since Massachusetts residents began fighting a proposed natural gas compressor station in Weymouth, the controversial and now-operational project has mostly been an issue of local concern. Not anymore.

As a challenge to the compressor station’s permit to operate winds its way through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) — the agency in charge of approving interstate energy projects — some on the five-person body have signaled that they’re no longer interested in doing business as usual.

In a 3-2 vote last month, the commission began what some FERC experts are calling “a seemingly unprecedented” review process that not only raises questions about the future of the Weymouth Compressor, but has many in the gas industry worried about the fate of their current and future projects.

At the simplest level, this case is about whether FERC should hold a hearing to relitigate the Weymouth Compressor’s license to operate, known as a “service authorization order.” This happens all the time when project opponents appeal a FERC decision.

But two things make this situation unique: the potential precedent it could set, and the fact that FERC has a new commissioner who has promised to give more weight to climate change and environmental justice concerns.

What Is The Weymouth Compressor?

A compressor station is a facility that adds pressure to a gas pipeline system to give the gas a little boost and help it move long distances. Think of it like squeezing a tube of toothpaste; you apply pressure and the toothpaste shoots out.

Natural gas pipelines usually have compressor stations about every 50-100 miles, and there are about 1,700 of them nationwide.

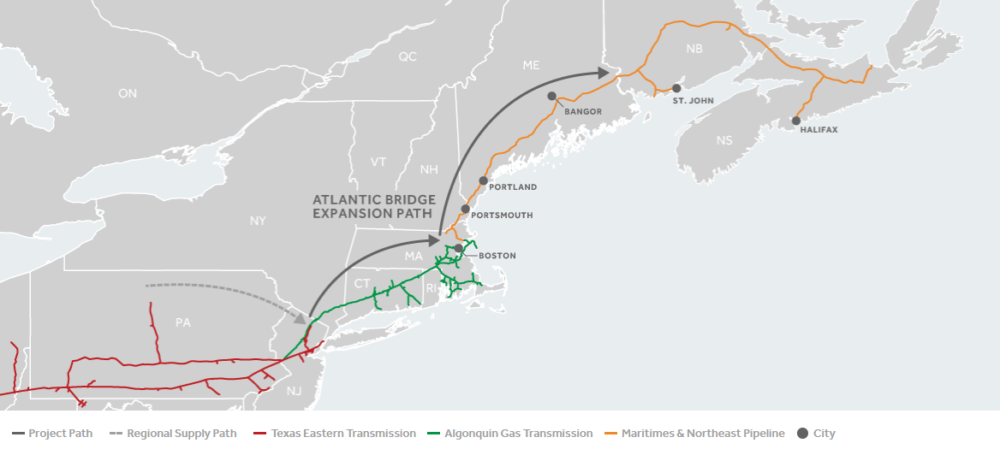

The Weymouth Compressor was designed to be the linchpin of a large interstate gas pipeline system called the Atlantic Bridge Project. The project connects two pipelines and allows fracked natural gas from western Pennsylvania to flow through New Jersey and New England, and into Maine and eastern Canada for local distribution.

Though no public opinion polling about the compressor exists, there is intense opposition to it here in Massachusetts. From activists groups like the Fore River Residents Against the Compressor (FRRACS) and Mothers Out Front, to elected officials, the anti-compressor movement here is vocal and visible.

The opposition tends to focus on four issues:

Public health and safety: Though rare, compressor stations occasionally catch fire and explode. For this reason, most are built in rural places. The Weymouth Compressor, however, is in a densely populated area that’s prone to flooding and near a busy highway. The site itself is near schools, senior housing and a mental health facility.

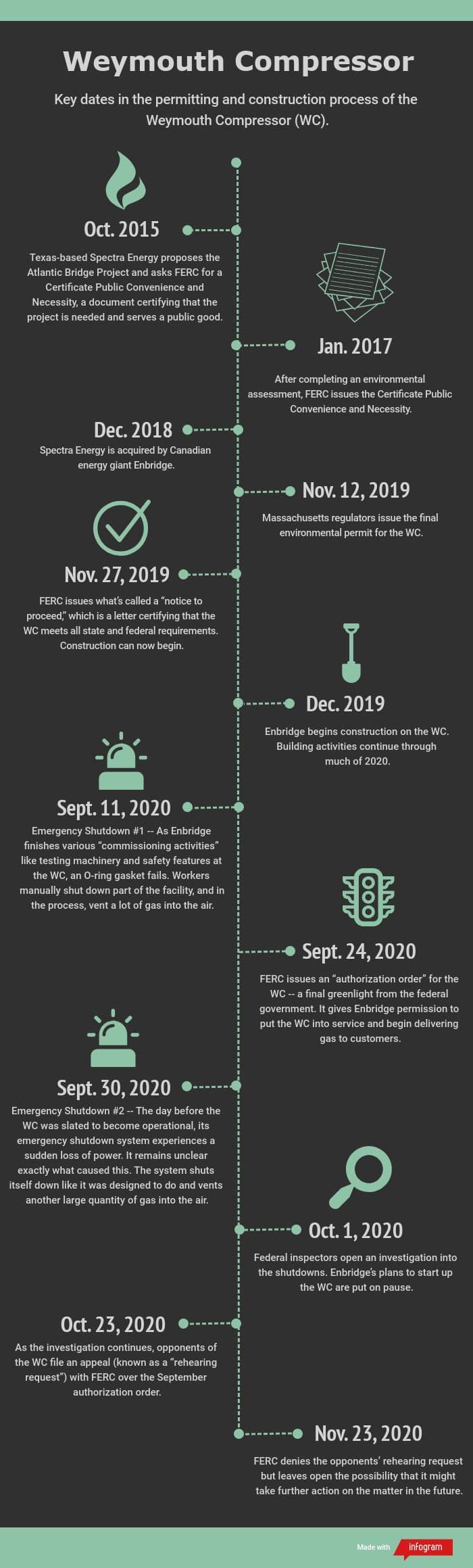

Safety concerns about the compressor increased after two unplanned shutdowns in September triggered a federal investigation.

Environmental justice: Weymouth has a long history of air pollution and soil contamination. The compressor site is near two state-designated “environmental justice” communities, not to mention a gas-fired power plant, a chemical plant, a sewage pelletizing plant, a gas metering station and the highly trafficked Fore River Bridge.

Residents in the area have statistically higher rates of cancer, pediatric asthma and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and according to the Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility, the “compressor station is, even by data provided by the company itself, likely to worsen the health and safety at this already at-risk community.”

Climate change: Between growing evidence that natural gas pipelines emit a lot of the potent greenhouse gas methane, and the fact that the compressor station will periodically release gas and other volatile organic compounds during “blowdowns,” many environmentalists worry about the project’s climate impacts.

They also argue we shouldn’t be building new pipeline infrastructure at a time when scientists warn that we need to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels.

Whether the project is needed: When the compressor was first proposed, the developer said it had customers lined up to buy the gas. In the years since, that picture has changed. Enbridge, the company that now owns and operates the Weymouth Compressor, says it currently has contracts with six gas distribution companies in Maine and Canada, though it declined to say how much gas each receives. Anti-compressor activists are skeptical about the actual demand, and maintain there are enough questions to warrant another look from federal regulators.

(For a deeper look at who opposes the project and why, check out our explainer.)

FERC Debates The Weymouth Compressor

In January, during its monthly public meeting, FERC discussed whether to officially deny the opponents’ request to “rehear” the authorization order that allowed the compressor to start up.

Three commissioners — Richard Glick, Allison Clements and Neil Chatterjee — noted that the project brings up serious environmental justice, health and safety concerns, and said they would vote “no” on the motion to deny the rehearing.

That’s a lot of negatives, we know. But the important thing to note is that three out of the five commissioners signaled that they have serious questions about the Weymouth Compressor and could be willing to take another look at it. (There was no vote on whether to actually schedule a hearing, though.)

After the meeting, Glick took to Twitter: “The Weymouth Compressor Station raises serious environmental justice questions, which we need to examine. The communities surrounding the project are regularly subjected to high levels of pollution & residents are concerned emissions from the station will make things worse … In 3 years at FERC I’ve seen little more than lip service paid to environmental justice. That needs to change.”

Advertisement

The tweet left the compressor's opponents optimistic, a feeling that increased after President Biden made Glick the FERC chairman on Jan. 21.

Their excitement, however, did not last long. A day later, the federal government concluded its investigation into the September shutdowns and told Enbridge it could start up the compressor. The facility was in service by the end of the week.

At its February meeting, FERC once again took up the Weymouth Compressor. The commissioners discussed a proposal to establish a comment period known as “a paper briefing process.”

The goal was to get answers to five questions:

- Is it consistent with FERC’s Natural Gas Act responsibilities to allow the Weymouth Compressor Station to enter and remain in service?

- Should changes in the station’s projected air emissions impacts or public safety impacts cause the Commission to reexamine the project?

- How might these changes affect the surrounding communities, including environmental justice communities?

- Should FERC impose any additional mitigation measures in response to concerns that have been raised?

- What would the consequences be if FERC were to stay or reverse the September 2020 authorization order?

Why This Paper Briefing Process Matters

While a paper briefing process itself is not significant or uncommon, FERC doesn’t usually hold one in a situation like this. Gillian Giannetti, a senior lawyer with the watchdog group The Sustainable FERC Project, says she can’t think of a time when commissioners have signaled as strongly that they’re willing — if not outright interested — in reexamining a project that was already in service.

“I think FERC is taking the position that it's important to take a stand and show that it is an agency that listens and cares about people's concerns,” she says.

The paper briefing process also triggered a striking response. Since the last FERC meeting more than 60 organizations, companies, interest groups and individuals have filed motions to become “intervenors” — essentially, legal participants in the proceeding. (The Sustainable FERC Project is one of them.)

The outcome of the briefing period remains unclear; FERC could vote to hold a hearing, or it could decide to take no action and let the compressor continue operating. But what is clear is that this uncertainty makes the situation more fraught.

Those in the gas industry, as well as those concerned about fossil fuel infrastructure, are left wondering about not only the future of the Weymouth Compressor, but also the fate of all other gas and pipeline projects.

“It seemed like the process was done. It seemed like it had all the approvals from [FERC] that it needed and those were final,” says James Coleman, a FERC expert and law professor at Southern Methodist University. And so for FERC to potentially revisit it “is a big issue for really anybody interested in building energy infrastructure around the United States.”

Giannetti, of the Sustainable FERC Projects, agrees. Imagine you were a gas company with “a project that is built, in service and has a FERC certificate that's 4 years old, and then something happens at one of your compressor stations — some safety issue,” she says. “There's a concern that this is an attempt to reopen and relitigate FERC authorizations that happened in a different FERC, in a different era.”

The Dissenting Commissioners

Two FERC commissioners — James Danly and Mark Christie — voted against the paper briefing process. In public comments and written dissents, they argued that it was illegal and bad policy.

“Intended or not, the message from this order is clear: even if a pipeline has its certificate, a court upholds that certificate, and that pipeline is in compliance, the Commission can now find a way to modify, or even possibly revoke, the certificate," Danly wrote.

Christie made a similar argument: “The majority’s order unquestionably raises the specter of shutting down this completed and functioning project even permanently,” he wrote. “Today’s capricious action violates the most basic standards of regulatory due process and regulatory finality, both of which are absolutely necessary.”

Both men said they believe the briefing process violates the Natural Gas Act and their congressionally approved authority. And at the February meeting, Danly put a finer point on what he sees as the big picture.

“This order by its plain terms casts doubt on every certificate that is held by every natural gas company across the country," he said. "It threatens the finality of orders we issue."

Danly encouraged Enbridge to appeal the decision and suggested gas companies get involved. Motions to intervene began appearing in the federal docket a few days later. (Enbridge filed its appeal Friday evening, after publication of this story.)

More Than 60 Intervenors

There’s a wide range of parties filing to intervene. In the gas world, applicants include the Maine Public Utilities Commission, which holds contracts for gas that goes through the Weymouth Compressor, to major industry groups like the Natural Gas Association of America and The American Gas Association.

The list also features energy giants like Kinder Morgan, which transports about 40% of the natural gas used in the U.S., and the Electric Power Supply Association, which represents companies like BP, Shell and Calpine Energy.

On the environmental advocacy side, there are local groups like 350 Massachusetts for a Better Future, the Conservation Law Foundation and the Pipeline Awareness Network for the Northeast, as well as big national organizations like the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

A number of South Shore residents and politicians like House Speaker Ronald Mariano, state Sen. Patrick O’Connor and state Rep. James Murphy have filed to intervene, as have academics like public health expert and Boston College professor Philip Landrigan, and Boston University professor and environmental activist Nathan Phillips.

The list goes on and on; other notable parties include Attorney General Maura Healey, the Weymouth School Board, the Town of Braintree and the Unitarian Universalist Mass Action Network.

Some applicants explained why they were intervening in their filing, and WBUR reached out to several more. Here’s some of what we heard:

- Iroquois Gas Transmission System: “We are concerned that the latest development in this proceeding calls into question the finality of the FERC process, which is a concern to all interstate pipelines who are anticipating making future infrastructure investments.”

- Eastern Shore Natural Gas Company: "Prior to the issuance of the February 18, 2021 Order Establishing Briefing, Eastern Shore had no reason to intervene ... However, the Feb. 18 Order requested briefing on topics that extend beyond the immediate project and that could have a causal relationship to Eastern Shore and the natural gas industry as a whole.”

- Tom Kiley, CEO of Northeast Gas Association: “If FERC were to do [this] then wouldn’t that open up every project of all types, all fuels, to be challenged? Anybody that was opposed to something could have another shot at that.”

On the other side, intervention applicants said they filed because they see this as a second chance to get their concerns heard, and they hold out hope that FERC will reverse its authorization order.

- State Sen. Patrick O'Connor: “The siting of that compressor station in North Weymouth — the Fore River Basin — is one of the most irresponsible sitings of energy infrastructure [in the U.S.], in my opinion … I think the government really needs to understand that people aren't going to take rubber stamps anymore.”

- Philip Landrigan, public health expert: “All of these groups are joining together and they're catalyzed by the recognition that a very poor job was done in the health impact assessment several years ago. There's a real opportunity against the background of this incomplete piece of work to overturn the decision.”

- Dr. Brita Lundberg, Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility: “FERC specifically asked about what safety and environmental justice issues we know about now that we did not know about when the project was approved. … I find it a very hopeful sign that FERC is now offering to listen. … There is still the opportunity to do the right thing.”

Bottom line, says FERC expert Giannetti, it’s not uncommon for there to be so many parties interested in intervening in high-profile projects. It’s just that, until recently, the Weymouth Compressor did not fall into this category.

While the project has been “extremely contentious on Twitter and extremely contentious in New England, it has largely been a sleeper docket at FERC for a long time,” she says. “And then FERC did something that is very newsworthy, very intriguing. And it’s bringing eyes to this proceeding that would not have otherwise been there.”

“It's sort of [its] Dakota Access Pipeline moment,” Coleman says.

A Changing FERC

There’s one other big factor in the background: the shifting priorities and dynamics within FERC.

By law, FERC can’t have more than three commissioners from the same party. The current makeup includes three Republicans: Danly, Christie and Chatterjee, and two Democrats: Glick and Clements. In June, Chatterjee’s term will be up and Biden will appoint another (likely Democratic, and likely progressive) commissioner.

Glick, the current chairman, has been outspoken about his belief that FERC needs to give more consideration to the climate change and environmental justice impacts of the projects it reviews. He has also made moves to establish a new Office of Public Participation at FERC and announced a new senior position dedicated to environmental justice and equity.

“This position is not just a title,” Glick said in a recent statement. “I intend to do what it takes to empower this new position to ensure that environmental justice and equity concerns finally get the attention they deserve.”

According to Giannetti and Coleman, those recent comments, plus his vote in favor of the briefing process for the Weymouth Compressor, signal Glick’s desire to end FERC’s reputation as a “rubber stamp” for fossil fuel companies.

What’s more, FERC is planning to update its policy statement — its North Star, so to speak — which sets guidance for assessing whether a project is needed, safe and in the public interest.

As FERC reevaluates its priorities, the coming appointment of a new member brings even greater expectations for change.

“Do I expect a FERC that has a Democratic majority to be different than the FERC we saw for most of the Trump administration? Absolutely,” Giannetti says. “In terms of what's going to be different, I don't really want to get ahead of the agency. But I can say this much, Commissioner Glick has made it clear that environmental justice is a huge concern of his.”

What exactly this all means for the Weymouth Compressor remains to be seen. But the very real possibility that FERC could decide to take an unprecedented step like revoking or staying the project’s authorization order, has meant that for now, all eyes in the gas world are on the compressor.

This article was originally published on March 19, 2021.

This segment aired on March 24, 2021.