Advertisement

The Controversial Natural Gas Compressor In Weymouth, Explained

For the last five years, a coalition of South Shore towns, politicians and local activists have tried to block the construction of a natural gas compressor station in North Weymouth. They’ve waged public awareness campaigns, challenged the project’s environmental permits in court, and even resorted to civil disobedience. Meanwhile, the company building the compressor station cleared every legal and regulatory hurdle in its way, and construction has moved forward.

The Weymouth compressor itself is a complicated project that involves multiple state and federal agencies and private companies — and that’s before you factor in all the litigation and local controversy the facility has generated.

WBUR published an explainer about the compressor station in June 2019, but given how much has happened since then, we felt it was time for an update. So once again, whether you've been reading about the issue for years and have questions, or are just hearing about the project for the first time, here's what you need to know:

What's a compressor station?

Compressor stations are a critical part of natural gas pipelines systems. As gas flows through a pipe, friction and turbulence naturally slow it down. By compressing the gas, these facilities “boost” pressure in the pipeline and help move the gas long distances.

There are five existing compressor stations in Massachusetts — one each in Hopkinton, Mendon, Charlton, Agawam and Southwick — and another 1,700 or so across the country.

What's the Weymouth compressor?

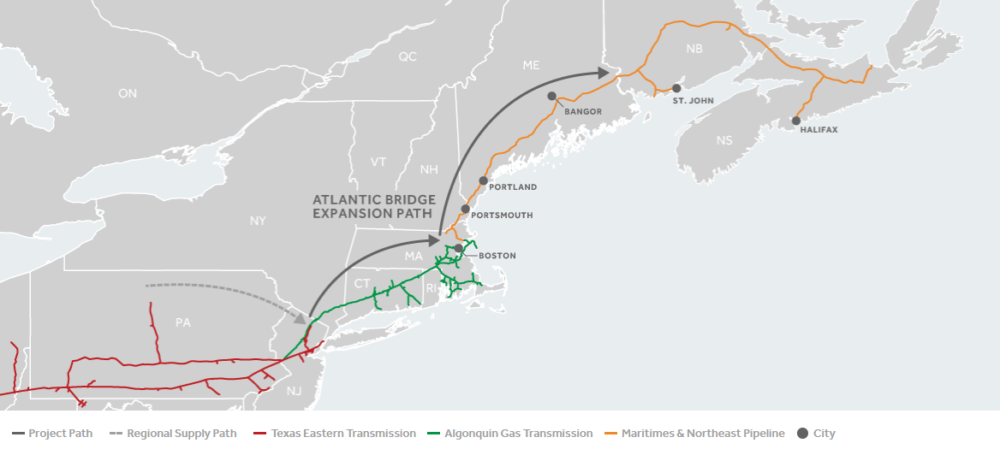

The 7,700-horsepower Weymouth compressor is part of a larger gas pipeline plan called the Atlantic Bridge Project. The purpose of the project is to make it easier for “fracked” natural gas from the Marcellus Shale of western Pennsylvania to get to northern New England and Canada, and it does this by connecting two existing pipeline systems: the Algonquin Gas Transmission, which flows from New Jersey into Massachusetts, and the Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline, which flows from Massachusetts to Nova Scotia, Canada.

(“Fracking,” or hydraulic fracturing, is a technique for extracting natural gas. It involves drilling deep into the earth and injecting a high-pressure liquid — usually water, sand and other chemicals — into bedrock to force the gas out through fissures or other openings. The technique has been around for decades but took off in the U.S. during the mid-2000s. Because of the environmental and health risks associated with fracking, the process is controversial.)

Who is building the Weymouth compressor?

As is often the case with big energy projects, there are a few companies involved including Algonquin Gas Transmission, Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline, Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline Limited Partnership and Spectra Energy.

But the important name to remember is Enbridge.

Enbridge Inc., a $170-billion energy company based in Canada, is the parent company to all the smaller companies involved in the Atlantic Bridge Project.

Enbridge makes most of its money by transporting Canadian crude oil into the U.S., but natural gas is also a big part of its business. According to the company’s website, it has about 23,850 miles of gas pipelines in North America, and transports “about 19% of all natural gas consumed in the United States.”

Who opposes it?

Though no public opinion polling about the compressor exists, there is widespread opposition to the project in Massachusetts.

Leading the fight are environmental groups like FRRACS (Fore River Residents Against the Compressor Station), Mothers Out Front, the Sunrise Movement, the Sierra Club of Massachusetts and 350 Mass For A Better Future.

The Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council — the regional planning association representing 101 cities and towns in the Greater Boston area — have also been vocal in their opposition to the project.

Local elected officials who oppose the compressor include:

- Weymouth Mayor Robert Hedlund

- Quincy Mayor Thomas P. Koch

- Braintree Mayor Charles Kokoros

- The Hingham Selectboard

- State Sen. Patrick O’Connor and State Rep. James M. Murphy, whose districts include Weymouth

The area’s U.S. Congressman, Rep. Stephen Lynch, is also a vocal opponent of the project. So are U.S. Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey.

Attorney General Maura Healey also opposes the project but has a more complicated relationship to it. During the siting phase of the project, Healey raised concerns about public health and safety to federal regulators, and she asked the state’s Department of Public Utilities to reconsider whether Massachusetts ratepayers should pay for construction.

But her job as AG also requires her to defend state agencies in litigation, including some ongoing lawsuits related to the compressor. So despite repeated calls from anti-compressor activists to take a more prominent role in the fight to shut down the facility, her primary responsibility is to work with other state agencies to make sure all public health and environmental regulations are followed and enforced.

Gov. Charlie Baker’s position on the compressor is harder to pin down. While he acknowledges the public’s health and safety concerns about the facility, he’s stopped short of ever criticizing it. Baker also tends to frame the project as being out of his hands — often noting that federal regulators have primary jurisdiction over interstate pipeline projects — even though Enbridge needed to get multiple environmental permits from the state to begin construction. To critics of the compressor, Baker’s reluctance to denounce it is tantamount to tacit support, and he’s a frequent target of their ire and activism.

Why are people opposed to it?

Opposition to the compressor tends to focus on four things: public health and environmental justice, safety and emergency response plans, climate change and whether the project is actually necessary. Let’s tackle these one-by-one:

1. Public health and environmental justice concerns: North Weymouth is a densely populated area that’s already burdened by industrial activities. It includes two state-designated “environmental justice” communities, and has a long history of air pollution and soil contamination.

The compressor site — known locally as the North Parcel — was built from landfill at a time when people used all manner of garbage and industrial materials to extend a city’s shoreline. It also served as a dumping ground for coal ash, and as a storage site for an 11.2 million gallon above-ground diesel fuel tank. (To learn more about the legacy pollution problems in the North Parcel, read our explainer: Arsenic And Diesel As Thick As Peanut Butter: What’s Below The Future Weymouth Compressor?)

State data already shows that residents have statistically higher rates of cancer, pediatric asthma and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and according to a 2019 report from the group Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility, the “compressor station is, even by data provided by the company itself, likely to worsen the health and safety at this already at-risk community.”

2. Concerns about safety and emergency response plans: Unlike most compressor stations, which are built in secluded or rural areas, the Weymouth compressor is in a densely populated area with about 3,200 people per square mile. The site is also very close to the highly trafficked Route 3A, and sits less than 1.5 miles from schools with more than 3,000 students, elderly housing, nursing homes and a mental health facility.

The area, according to a report from The Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility, “is prone to flooding with even moderate storm surges, let alone a hurricane storm surge, and is frankly inappropriate for building any new infrastructure — much less potentially explosive infrastructure.”

Major accidents at compressor stations are rare, but not unheard of. In early 2019, a cold snap caused a Michigan compressor station to release a large quantity of methane, which then caught fire and exploded. A few months later, a compressor station in West Virginia caught fire and exploded as well.

While thankfully no one was injured in either incident, people who live near the Weymouth compressor worry that if a similar accident happened, they might not be so lucky. Many opposing the compressor say the 2018 Merrimack Valley gas explosion, which killed one teenager and injured more than two dozen people, was a reminder of the potential dangers of natural gas, and that the two emergency shutdowns and unplanned gas releases at the compressor this past September resurfaced those fears. (More on the recent shutdowns later.)

Concerns about a disaster have been compounded by the lack of public emergency or evacuation plans, and in 2017, following public outcry, Gov. Baker asked the state’s Departments of Public Safety and Security and the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs to “facilitate an opportunity for the public to bring their concerns directly to PHMSA [the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.]”

Many Weymouth residents were hoping that the state agencies would issue a formal report assessing safety concerns — like they did for health concerns about the project — but that seems very unlikely. According to a spokeswoman for Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, the state has already done its part to address public safety concerns:

“Since 2017, the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security has engaged local officials, public safety agencies, the Emergency Planning Council, and other stakeholders to ensure that local concerns are fully understood by state officials and properly relayed to PHMSA as a safety and compliance agency.”

Meanwhile, the town of Weymouth, which is responsible for coordinating the local emergency and evacuation response should an accident occur, says it’s been working on the plans and expects to publish them in late October 2020.

3. Concerns about fossil fuels and climate change: Burning natural gas for heat emits less carbon dioxide than burning oil, but it still contributes to climate change. Many local environmentalists say they are baffled that we're building new gas pipeline infrastructure while scientists are telling us to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels in order to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. To opponents of the Weymouth compressor, the project feels anathema to our state emission reduction goals.

The climate concerns aren’t limited to the uses of natural gas. Compressor stations themselves vent the potent greenhouse gas methane — as well as other harmful volatile organic compounds — during “blowdowns,” the routine gas releases that relieve pressure in the system. (There's also increasing evidence that gas pipeline infrastructure leaks much more methane into the atmosphere than we previously knew.)

Thus for many in Massachusetts, the Weymouth compressor has come to symbolize bigger environmental and health problems associated with fossil fuels, and fighting it has become a microcosm of the adage, “think global, act local.”

4. Actual need for the project: In order to build the compressor station, Enbridge needed to prove to the federal government that there was a "need" for the project. It did this by demonstrating it had customers lined up to use the gas in its pipelines. Enbridge secured eight contracts, but last year, two of its customers sold their capacity shares to another utility. And while there’s nothing odd about the buying and selling of contracts like that, the utility who bought them, National Grid, told WBUR that it didn’t need the Weymouth compressor to get gas to its customers.

A little more digging revealed that two more utilities with contracts, Eversource and Norwich Public Utilities in Connecticut, also don’t need the compressor. In practice, what this meant is that the only beneficiaries of the compressor station are in Maine and Canada.

For Massachusetts ratepayers who are footing much of the bill, and Weymouth residents who are absorbing the physical risk, this doesn’t seem fair.

Why doesn’t Enbridge build the compressor somewhere else?

Enbridge considered seven alternative sites for the compressor station, including three other locations in Weymouth. But after analyzing the options, the company chose the proposed site for a few reasons.

First, Enbridge notes that the North Parcel is already near the junction of the two gas lines it wants to connect, so building the facility there would “not require construction of any additional pipeline outside of the compressor station property.” This means it will be less disruptive to local landowners, forests, wetlands, water bodies and public roads than any of the alternatives, the company says.

Enbridge also liked the Weymouth location because it’s close to other industrial facilities like “the Fore River Bridge, a gasoline/oil depot, a chemical plant, and a sewage pelletizing plant.” Critics of the project, however, say the proximity to these things is itself a public safety threat because an accident or fire at one could cause problems at others.

In a 2015 report, Enbridge concluded that the proposed site “strikes the optimal balance between the requirements of compression … while minimizing environmental disturbances, expense, and maintaining service to the existing customers.”

Who signed off on this project?

Before building the Weymouth compressor, Enbridge needed several state and federal permits. The process began with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which oversees interstate pipeline projects.

FERC approved the project in 2017, but before construction could begin, Enbridge needed the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) to grant three permits: an air quality permit, a wetlands permit and a waterways permit. Of the three, the air quality permit was the most contentious.

(If you want to get deep into the weeds about the battle over the air quality permit — and how an investigative reporter uncovered that MassDEP didn’t initially publish all of the findings of its air quality study — read our original explainer.)

After receiving the necessary state permits, Enbridge turned back to FERC and asked for permission to begin construction. On Nov. 27, 2019 FERC issued a “notice to proceed. That gave Enbridge a green light to break ground, which it did in December 2019, and less than a year later, FERC gave Enbridge permission to put the finished station “into service” on Oct. 1, 2020.

You mentioned that there were two emergency shutdowns in September before the station even opened — what happened?

Enbridge spent much of September “commissioning” the compressor station — testing its various mechanical parts and safety systems, and getting it ready to go into service. But on Sept. 11, an O-ring gasket failure required workers to manually trigger the station's emergency shutdown system and vent about 169,000 standard cubic feet of gas, including 35 pounds of volatile organic compounds. Though Enbridge says the gas was vented in a controlled and safe manner, some portion of it was released at ground level where critics of the project say it's more likely to ignite and explode.

Enbridge said it fixed the problem and was soon back to work commissioning the facility.

But then on Sept. 30, one day before the station was supposed to go into service, some sort of electrical problem triggered the emergency shutdown system, and the station released 195,000 standard cubic feet of gas and 27 pounds of volatile organic compounds through the tall vent stack into the surrounding area.

Following public outcry about the gas releases, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) opened an investigation into the two incidents. The following day, Oct. 1, the agency told Enbridge that it can’t restart the compressor until the federal investigation is complete and a series of mechanical “corrective actions” have been met.

“Continued operation of the Station without corrective measures is or would be hazardous to the life, property, or the environment, and that failure to issue this Order expeditiously would result in the likelihood of harm,” PHMSA Associate Administrator Alan K. Mayberry wrote in a Corrective Action Order.

He added that while “there were no injuries or fatalities associated with the [Sept. 11 and Sept. 30] Incidents … the release of large quantities of natural gas in a heavily populated areas carries a substantial risk of fire, explosion, and personal injury or death and releases harmful methane into the environment.”

On Oct 2, U.S. Rep. Lynch toured the compressor station and told the public that the FBI was also getting involved.

“Because this is an international pipeline, and because of the national security implication, the FBI has been asked to take a look at any possible cyber intrusion that might have triggered the release,” Lynch said. The FBI declined to comment or clarify whether it was conducting an investigation.

So what happens now?

It's unclear how long it will take Enbridge to address PHMSA’s corrective action plan, but the company says it's committed to working with federal officials and will start operations only when it's "fully confident" that the facility is safe.

Opponents, meanwhile, say they're continuing the fight against the compressor by challenging some of the state permits and pushing for policies that reduce the region's demand for natural gas.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to reflect revised figures on the scale of the two gas releases in September 2020.