Advertisement

'We Knew The Inevitable': Why Mass. School Leaders Had To Close Schools On Their Own

Resume

At 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, March 11, senior school leaders in Framingham were chatting and getting coffee in a conference room. It was a rare mandatory meeting at their main office. They expected to gather for just an hour to map out what would happen if they had to close schools because of the coronavirus.

“We had no known cases, but there were cases popping up and we knew the inevitable,” recalled Framingham school Superintendent Bob Tremblay. “And it was probably a day too late.”

Shortly after the meeting started, a phone rang. The city’s director of public health, Sam Wong, stepped into the hallway. When he opened the door again, he motioned for Tremblay. The staff waited anxiously.

Wong told Tremblay a parent of a student at the Potter Road Elementary School had tested positive for the coronavirus in connection with a recent Biogen meeting. The child had mild symptoms, too.

Tremblay knew he had to close the Potter Road school immediately.

“The next big realization was: wait a minute, if this child had mild symptoms now, he probably had those same symptoms an hour ago,” he said. “And he was on a bus ... with kids from another school.”

Tremblay walked back into the conference room, stood behind a chair and told his staff the news.

“I said, ‘I think we have a kid,’ ” he said. “You could just see that everyone's face was like, ‘OK, this just got real.’ ”

And it got critical. Classes were starting at the school in less than 30 minutes. Immediately, Tremblay divided everyone into smaller groups and assigned tasks. Track down all students and staff who might have had contact with the symptomatic student. Inform those families and advise them to self-quarantine for 14 days. Tell bus drivers to stand by in order to bring kids home.

Some of the Framingham families who needed to quarantine didn’t speak English. Tremblay brought translators into the room. They wrote all official messages into Spanish and Portuguese simultaneously, working in Google docs.

“This escalated, as you can imagine, pretty quickly,” Tremblay said.

The fast pace is not only a testament to the highly contagious nature of the coronavirus, but also how federal and state officials struggled to stay ahead of — let alone keep pace with — what was happening in local communities. In the midst of the crisis, school officials were effectively asked to act as epidemiologists, tasked with making their own calls about the risk of spread in their schools.

School closures in Massachusetts unfolded rapidly and haphazardly over four days in March, even though there had been warnings and mounting evidence about the seriousness of the disease for months. When WBUR examined the decision-making behind school closures across the state, it found districts were unprepared to respond to a pandemic, and state leaders failed to provide specific directives until the need to act was undeniable.

What happened before statewide school closures in Massachusetts demonstrates how traditional approaches to emergency management, which elevate local control, fall short during a global public health crisis.For educators, that decentralized approach created confusion and frustration. It also left local leaders making potentially life-and-death decisions with imperfect information and inadequate guidance.

Slow Emergency Response

On Feb. 1, Massachusetts announced its first confirmed case of the coronavirus. He was a student at UMass Boston. It was the eighth case in the United States.

Throughout February, much of the guidance from state and federal officials focused on international travel. Superintendents like Dianne Kelly in Revere were concerned. In mid-February, a group from Revere High School traveled to Italy for school vacation. As Kelly watched the number of cases erupt in Italy, she took a closer look at the group’s itinerary. It included a two-night stay in northern Italy, the hardest hit part of the country.

Kelly contacted the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for guidance. She was told the students and staff could return to school but should be monitored for signs of illness. They came back. No one showed any symptoms.

“We immediately had a bit of a smaller uprising from other parents who felt like we were putting their kids in jeopardy, in harm's way, by admitting kids who had recently traveled to Italy,” Kelly said. “So we were already acutely aware of how the general public was responding to the coronavirus ... and we spent a lot of time really trying to reassure parents.”

But a week after students returned, federal officials revised their guidance. Anyone who had traveled to northern Italy since Feb. 15 should isolate for two weeks.

“That just put everybody in a tailspin,” Kelly said. “Because then we had to tell those kids and those adults who traveled to Italy to stay home.”

State and federal health authorities still advised schools to consult with local boards of health. But superintendents wanted detailed answers from the Baker administration about what they should do to keep people safe. (Gov. Charlie Baker and state education leaders did not comment for this article.)

Typically, disaster response is carried out at the local level, under state management and with federal support.

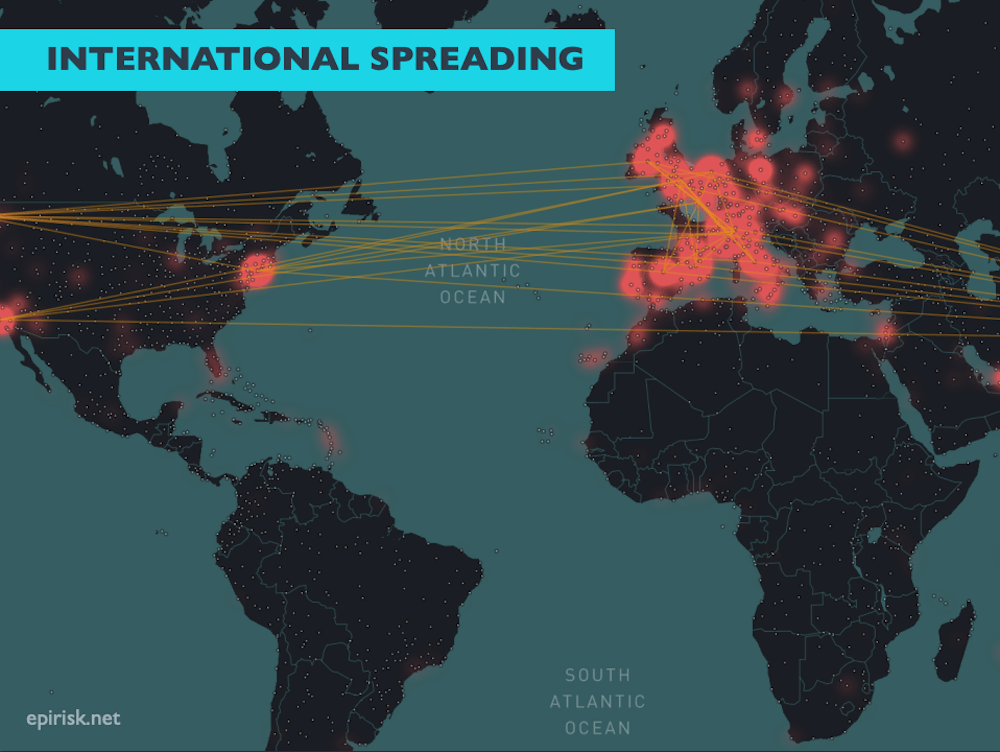

“We all have to move in concert with one another to have the best effect, and yet we are really trying to keep it very locally driven,” said Margaret Bourdeaux, a physician and global health researcher at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and Harvard Medical School. “That just leads to this kind of patchwork effect that you're seeing, and schools are but one example of that.”

Reliance On Local Networks

In the absence of specific federal or state guidance about what should trigger school closures, superintendents turned to each other.

About a hundred emails circulated through the superintendents’ listserv each day. And there were lots of questions.

“How do we deal with families or parents who've been traveling? Who do we self-quarantine? Is it just the family that was there? How do we deal with the children?” recalled Tom Scott, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents.

The association set up shared Google drive folders to organize what various boards of health were advising, what resources they were using and what superintendents were telling teachers and families. Scott asked for a conference call between district leaders and state education Commissioner Jeff Riley. It took place March 6.

The timing of that call came at the confluence of several key developments in the spread of the coronavirus in Massachusetts. The previous evening, the state confirmed that a Tennessee man who had traveled to Boston had tested positive for the coronavirus. He had come to town for the Biogen conference, and several other attendees were reporting symptoms.

“I think the tone was very much like: we are watching this, we're going to see what happens,” said Revere school superintendent Kelly. “There was no talk at that point about: we should be planning for a shutdown.”

Even as public health officials traced the potential spread from the Biogen meeting, Gov. Baker said the risk to the public was low.

But as testing slowly increased, so did the total number of positive cases in Massachusetts — and some of those cases were connected to schools. That ripple effect led some local boards of health to recommend schools close. Parents with medical backgrounds urged school closures, too. At the same time, state health officials were still not advising broad school closures.

“I think a lot of that created a sense of anxiety and confusion,” Scott said. “And so that's when things begin to break loose.”

A Coordinated Local Response

On Thursday, March 12, at 9 a.m., leaders from 30 municipalities met at Partners HealthCare headquarters in Somerville to listen to a panel of epidemiologists and other experts talk about the coronavirus.

"There was really frustration,” said Somerville Mayor Joe Curtatone. “There was a lot of confusion because it was a loose set of guidelines, there wasn't a lot of direction.”

In the 36 hours before the meeting, Gov. Baker had declared a state of emergency, area colleges decided to move courses online and students off campus, and the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic. The researchers explained what was happening in countries like China and Italy, and what could happen in the U.S.

“What they said to us, to a tee, was startling,” said Curtatone, who chairs the Metropolitan Mayors Coalition and co-hosted the meeting with Boston Mayor Marty Walsh. “We didn't have weeks to act. We barely had days and we might be too late.”

The biggest concern was overwhelming hospitals.

The leaders agreed they could not make decisions on how to mitigate the pandemic town-by-town, city-by-city. They needed to act together. Twenty-two mayors and town administrators sent a letter to Baker, calling on him to close all schools and provide more guidance.

“We feel strongly that if each municipality is left to respond to the crisis on their own, this ad hoc response will generate panic and confusion among our residents," the letter said.

Everett Mayor Carlo DeMaria was in Aruba, planning to celebrate his 23rd wedding anniversary with his wife Stacy. In between the meeting, other conference calls, texts and emails, the couple researched the coronavirus. DeMaria also received daily updates from his cousins in Italy.

“‘Take this very serious. We didn't take it serious,’” DeMaria remembered them warning. “I see the pictures they’re sending me of all these coffins in Italy and so forth, the amount of dead. And I'm saying, ‘My God, I gotta take some action.”

Some districts announced they would close for a week or two. The Everett public school system was the first to close for a full six weeks in Massachusetts.

Children were — and still are — generally believed to be less likely than adults to become severely ill after contracting COVID-19. But students are inextricably linked to the broader community, defying district lines.

DeMaria believed closing schools “was the best place to start” and prevent an escalation of the pandemic that mirrored what he heard from his family in Italy.

“To be honest, at that point, I was so relieved,” said Everett School Superintendent Priya Tahilani. “Yes, please, let's do it, because I'm getting nervous for the safety of our students, of our teachers, of their family members that they're going home to.”

It was her second week on the job.

Detailed Guidance Too Late

At 8:30 a.m. on Friday, March 13, Massachusetts health and education officials held their second joint conference call with school leaders. Around 1,000 people were on the line. State officials said they would not recommend statewide school closures, instead leaving the decisions up to the local authorities.

“We were still being told, 'You should keep schools open at this time,'” said Revere superintendent Kelly. “I felt like by that point it was a little bit tone deaf.”

As part of that call, the state did issue detailed guidance for school administrators. But Scott, with the superintendents association, said it was, “a little bit too late.” The majority of schools were already closing for one to two weeks.

On Friday afternoon, Gov. Baker held a press conference. He banned gatherings of more than 250 people. Colleges, universities and K-12 schools were largely exempt. Baker stayed in line with the CDC and his department of public health, and recommended “a surgical and fact based approach” instead of closing schools across the board.

Criticism began to mount from teachers, parents and physicians.

At 11 a.m. on Sunday, March 15, Gov. Baker appeared on WCVB-TV. He said he was not issuing a statewide shelter in place or stay at home order. Baker said without such an order, closing schools alone may not be effective at slowing the spread of COVID-19.

“The thing to remember here is you want to make your decisions based on the facts as they are, said Baker. “Now, if the facts change, our decision process will change.”

That afternoon, New Hampshire ordered statewide school closures. Vermont did the same.

At 6 p.m., Baker followed suit, closing schools through April 6. There was evidence of community transmission in seven counties.

“[The decision came] much too late,” Massachusetts Teachers Association president Merrie Najimy said. “It didn't leave us time to be prepared, and it did not give our schools a chance to reduce the possible exposure.”

A Baker spokeswoman did not respond to WBUR's questions about what changed for the governor in those days and hours. But last week, a reporter asked Baker if he would consider keeping school buildings closed for the rest of the year. Usually even toned, the governor became impassioned.

“There are a lot of kids for whom school is going to be the place where they have the biggest and best and most significant opportunity to get the kind of education they need,” said Baker. "And I don't want to start with the assumption that we're just going to blow that off for the rest of the year.”

Every school leader WBUR spoke to said they believed that the Baker administration was doing their best, given the circumstances. They also praised education commissioner Riley. Still, they said existing state-mandated emergency response plans are grossly inadequate for a modern pandemic.

“It just wasn't on the scale,” said Kelly, of Revere. “It talked more about how to respond to a pandemic in terms of sites for vaccine distribution and things like that. [It] didn't talk about what if we have to shut the schools down altogether and learn from home. This is all uncharted.”

But it was predicted in many ways. Public health officials have been warning about the possibility of a global pandemic for the last decade, according to Bourdeaux, the global health expert.

Schools and business are being shut down now, “because we couldn't execute on the basic public health plan," Bourdeaux said. "So now our only tool in our toolkit is to keep people literally from touching each other.”

Millions of families and individuals are paying for multiple systemic failures. From state capitols to the White House, leaders didn’t see how interconnected communities are locally and globally. Locally, public health officials failed to recognize the highly contagious nature of COVID-19 from the start, and help community and school leaders respond in a coordinated manner.

In the months ahead, they will learn just how devastating and long-lasting those consequences will be.