Advertisement

Can you really get tics from TikTok?

Resume

For the past year or so, the medical community has been looking into a troubling trend: a surge of teens and young adults coming into clinics and emergency rooms with sudden and uncontrollable verbal and motor tics. The thing most of these patients seem to have in common? Spending a lot of time on TikTok and other social media platforms.

Parents, doctors, and daytime television hosts have been fascinated and terrified by this recent phenomenon—dubbed "a pandemic within a pandemic" by experts around the world. Sensational media coverage has certainly contributed to the hysteria.

But is one of the most popular social media platforms on the planet really to blame for young people developing tics overnight? Or is there more to this so-called "medical mystery" than meets the eye? We talk to neurologists and TikTok influencers to find out.

Nora Saks, an Endless Thread producer, is filling in for Amory Sivertson as co-host for this episode.

Show notes

- "TikTok tics are a symptom of a much bigger problem" (The Verge)

- "Gen Z is developing unexplained tics after going online, and doctors are concerned" (Vice)

- "Teen girls are developing tics. Doctors say TikTok could be a factor" (Wall Street Journal)

- "Tics and TikTok: Can social media trigger illness?" (Harvard Health Publishing)

- "TikTok tics: A pandemic within a pandemic" (International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society)

- Functional Tic explainer

- Interviewee Adele's TikTok page

- Jan Zimmerman's YouTube channel

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Nora Saks: Hello Ben!

Ben Brock Johnson: Wait a minute—you’re not Amory!

Nora: That’s a very astute observation.

Ben: (Laughs.)

Nora: This is Nora, I’m one of our producers. And today Ben, I’m keeping the co-host chair warm for Amory, who is allegedly off a-fjording in Norway.

Ben: And you’re also helping us understand a mystery that I have been spreading rumors about ever since I heard about this mystery at a dinner party at a relative’s house.

So, a few months back I was hanging with some of my best friends who also happen to be in my family: Will and M.E.

Will: If you want to be technical it’s a step situation, but…

Ben: Yeah.

Will: We’re siblings.

So, Will is technically my step brother in law and M.E. is Will’s wife.

M.E.: Am I your sister in law?

Ben: Step brother, sister in law?

Ben: Will and M.E. both do what I would describe, with some bias is very important work. Will is a physician’s assistant who works in an emergency room at a big hospital.

Ben: You’re giving people alive on a daily basis. (Laughs.)

Ben: And M.E. is a high school educator with lots of impact on what kids learn and how.

And they had both seen something, heard about something, in the course of doing their work that they started telling me about. Something that raised the hairs on the back of my neck.

Will had just come off a shift in a pediatric ER. And during that shift, a medical student mentioned that the hospital had just admitted a young patient who might have a TikTok tic.

Will: So I asked, like what are TikTok tics? And I think the explanation they gave was, it's this non-epileptic, uncontrolled movement that kids have after watching too much TikTok. I think that's the explanation I got.

Ben: Yep.

Will: And of course, we were all like, "That's crazy."

Ben: So also, M.E. interacts with teenagers in her classroom all the time, and as Will started to talk about this, M.E. weighed in and said she had noticed students with a lot of the same mannerisms.

M.E.: It's like different gestures and things that they do with their hands that is similar amongst different groups of kids that I have also seen online, whether it's TikTok or YouTube or whatever.

Ben: Will and M.E. were talking about different things. But generally speaking the ideas are connected. One of the most popular and addictive social media apps in the world—TikTok—is influencing not just how kids talk and move but it’s also maybe creating involuntary reactions in kids

These are sudden, repetitive, uncontrollable movements and sounds. Tics. Something involuntary. Like a hiccup.

And people are seeing this more and more. And they don’t yet have a full explanation.

Nora: When you first told me about this Ben, it sounded like maybe anyone can pick up some sort of tic just from binging TikTok. Which was a pretty vague, undefined rumor.

Ben: Nora, that’s not my job? To just like, you know, pass off vague and undefined rumors and conversations with people anecdotally and call that journalism? That’s not what we do here?

Nora: You can do whatever you want but that is not what I did when you told me about it.

Ben: (Laughs.) That’s why you’re a star. In my defense, of course, I wanted us to report it out in a responsible way. Because there has been a lot of this TikTok tic hysteria rippling around over the last year or so. And journalists admittedly have been amplifying it.

[Dr. Oz: Can social media be causing an epidemic of Tourette-like tics in teen girls?]

[ABC 7 newscaster: TikTok may be to blame for a recent rise in tics in teens.]

[NBC 6 newscaster: Yeah, but can videos trigger tics?]

Ben: The story we found with Nora’s help is a lot more complicated than one might find on the nightly news. And as more and more people are showing up in school or at the hospital with this bizarre disorder, studies are being conducted.

Nora: And parents like you are getting a little panicky.

Ben: Not just panicky. I was borderline—I was getting clammy!

Ben: This cynical, dystopian part of me is like, "Oh, yeah, of course. Of course, this app is like changing the way that people move in the world."

Nora: I shared your cynicism, Ben. And I’m guessing that’s because we’re both elder millennials.

Ben: Hey kid, get out of my chatroom!

Nora: Yeah, get your hands off my avocado toast! But luckily one of our teammates was able to connect us old millennials to the culture of the youths. Gen Z-er—or Gen Zed-er, since she’s Canadian—Meera Raman.

Ben: You're on TikTok, right?

Meera Raman: Oh yeah, I'm on TikTok too much.

Nora: Meera says when she first heard about this whole TikTok tics thing…

Meera: I'm gonna to be honest, I was pretty freaked out because legitimately I was like, do I have this? Full stop, no joke. Because my friends and I who watch TikTok and listen to trending audios all the time, we use those audios in our day to day speech. So I was like, is this what we do?

Ben: We, of course, wanted examples. So Meera, good sport that she is, played a game with her friends—where she started to say the beginning of a TikTok audio—

Meera: And I wanted them all to complete it.

Meera (to friends): OK, ready?

(Meera and friends sing and chant along as TikTok audio plays)

[“Don't be suspicious, don't be suspicious.”

“Immediately, no. Immediately no."

“Bullying. Knock it off. Racism. Knock it off.”]

Nora: Meera and her buds say this stuff incessantly, almost as a reflex. Now do they all have TikTok tics, she wondered? Could they end up in the ER?

Ben: The answer to Meera and her friends’ questions is nope. But TikTok tics are real.

Nora: So is the hysteria. And as we dug further into this “social media medical mystery”, we found a hodgepodge of real issues that some young people are dealing with.

Ben: That doctors, psychiatrists, and scientists are still trying to get their arms around. And so are we.

Ben: I’m Ben Brock Johnson.

Nora: I’m Nora Ruth Valerie Saks.

Ben: Wow, today I learned. Ruth Valerie Saks.

Nora: Oh, yeah.

Ben: Alright. I’m gonna use that somehow, I don’t know how yet. You are listening to Endless Thread—coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station.

Adele: I started tic-ing before TikTok. So it definitely wasn't TikTok that started my tics.

Nora: This is TikToker “MaybeMyahAdele”. Adele is currently in school in Florida. And the way she makes a living?

Adele: I am a content creator slash influencer, I guess is what my title would be.

Ben: Love a fellow content creator. Adele, though, has more than 400,000 followers on TikTok. Her content, which is a lot of lip syncing, acting, and princess-ing videos isn’t super niche.

[Adele on TikTok: Everybody shut up I think I finally figured out Encanto.]

Adele: I just like to make my page and my family, my online family, just like a really supportive, safe place.

Nora: At 19, Adele is already a veteran of social media. But a few years ago, around the time she turned sixteen, something weird started to happen.

Ben: Adele was taking a course in one of her favorite subjects—psychology—which is why she was doing homework that hadn’t even been assigned yet.

Adele: And I was reading ahead one night. I was reading about like, tic disorders and stuff like that.

Nora: Hungry to learn more, Adele hopped on YouTube. And found creators sharing their stories about living with tic disorders like Tourette Syndrome.

[Jamie Grace: Yeah, so I tic-ed 102 times in a 3 minute period. That’s a normal day for me.]

Ben: Intrigued, Adele began watching a bunch of YouTube videos like this. She went down a rabbit hole.

Adele: I was doing that for like a few weeks, maybe a few months. It was just something I did in my free time. And then I remember one day, I like, woke up and had these weird, like, muscle spasms that really mimicked some of the tics that I'd seen in the videos I was watching.

Nora: The first one she picked up...

Adele: It's like this jerking head motion, like almost like if you were to just turn your head to the left to like, touch your shoulder. Kind of like that, but just much more violent, because obviously you're not doing it voluntarily. I have like a clicking sound. They’re, honestly, just all kind of random which ones you pick up.

Ben: Can you um—I guess it's weird, I don't want to like trigger the the thing, but can you make the click sound like, is this a sound you make or what?

Adele: Yeah, it's a sound. I will do it. It might trigger it after, which is fine. But just so you guys know. But yeah, it’s just like a little, like (clicks, whistles.) Yeah, those were, those were a few. I think I picked up the whistle (whistles) as well. (Verbal tic.) Oh, sorry. (Verbal tic.) But I can't really remember. Oh, sorry, sometimes I forget my train of thought while that's happening. But yes, that's what it sounds like.

Ben: Even though you can find this stuff on social media, it was a little nuts to listen to Adele experience it in real time. Seemingly unable to control the clicking tic after opening the door. And an involuntary addition that she couldn’t suppress: that whistle sound.

Nora: And Adele told us that other tics she experiences include hitting herself or throwing things. She once threw her cell phone across the park. Occasionally, she’ll develop a full blown tic attack.

Adele: It's very violent, at least mine are.

Nora: Normally, they last 10 to 15 minutes.

Adele: It's like if you were working out at the gym, like your muscles are going to get fatigued and then you stop because your muscles are fatigued. But it's like, in this case, like, we can't stop, so it just keeps going. And then you're just really rundown after.

Ben: Adele seems pretty comfortable talking about this now. But she says when this first started up, she had no idea what was going on. She had no history of tics. It was all so weird and random, she wondered even if it was real.

Adele: Yeah, for a while I would think that it wasn’t an actual disorder and I was just making it up. But then I would be like completely alone and doing it, and they would be like painful. Or I would have a tic attack rather, in the middle of something that was important to me. And I'd be like, "OK, why would it be fake, clearly, this is not fake."

Ben: But this wasn’t happening to just Adele. In 2020—year 1 of the pandemic— doctors started seeing an explosion of these kinds of behaviors in their clinics.

Dr. Tamara Pringsheim: So, you know, I was getting sort of six referrals a week for young people with the sudden onset of these, of these symptoms. And I think that prior to that, I'd maybe see a couple of people a year.

Ben: Dr. Tamara Pringsheim runs the Tourette Syndrome Clinic at the Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary. She’s a clinical neurologist—meaning she does research and she also takes care of patients—kids and adults.

Ben: I think when a lot of people think about Tourette's...

Dr. Pringsheim: Mhm.

Ben: ...if they have any sense of it, essentially they're like, Yeah, it's when people swear and say really weird things very loudly in the middle of their sentences. And that is sort of where the definition ends for the average person in some ways.

Dr. Pringsheim: Mhm.

Ben: Can you give us a more nuanced or correct definition of what Tourette's is?

Dr. Pringsheim: Yeah. So Tourette Syndrome is a childhood onset neurodevelopmental disorder. It's very common. It affects about 1 percent of boys and one in 400 girls.

Ben: That is 4 times more common in boys, for those of you who don’t do maths all that well. Tics associated with Tourettes usually show up in early childhood and then wane in adolescence. And they creep in gradually.

Dr. Pringsheim: So typically, it's one tic at a time, beginning with simple tics involving the face.

Nora: Like a rapid eye blink. Or head nod. Or shoulder shrug.

Dr. Pringsheim: So while people often equate like, repetitive swearing or offensive statements with Tourette Syndrome, it's, it’s one of the less common symptoms of the disorder.

Ben: Dr. Pringsheim quickly realized that what she was seeing in her clinic in 2020 was not an explosion of Tourette Syndrome. An explosion of tic-like behaviors. Symptoms of what neurologists call a functional neurological disorder.

Dr. Pringsheim: The simplest explanation is that these are disorders of brain function rather than brain structure. We think of them as sort of a software problem rather than a hardware problem.

Nora: To go a little further with this analogy, imagine the software that controls your nervous system has a glitch in it. And that glitch makes your system go haywire, which can lead to physical symptoms. Like verbal and motor tics.

Functional Neurological Disorders—or FNDS—are rare. And they’re distinct from Tourette Syndrome in some key ways. For one thing, these “rapid-onset tic-like behaviors'' tend to appear overnight.

Dr. Pringsheim: And many patients can actually pinpoint the day that it started. You know, it started on Easter Monday when I was at the mall and it became incapacitating within the course of 24 hours or a few days.

Ben: Another big difference?

Dr. Pringsheim: The tics were more frequent. They were more complicated. They are more intense. All of it.

Ben: Something else that was super unusual?

Dr. Pringsheim: The symptoms that we were seeing between people were so similar. So like, one week I saw like, I think three or four people who were all saying the same word. They were all saying the word beans. And I, I can tell you that, like over the past 12 years, I never saw anybody who said that specific word.

Nora: Others were thumping their chest, or hitting themselves in the head. Some cases were so serious, Dr. Pringsheim got called to the ER.

Dr. Pringsheim: Many kids weren't going to school because of it. I had adults who couldn't work. You know, it was interesting in the sense that the level of disability was so high. Much higher than my patients with Tourette Syndrome.

Nora: And this outbreak was also hitting a different demographic. The majority of referrals Dr. Pringsheim was getting were for adolescent girls and young women. Between the ages of 12 and 25. In other words, more girls and more Gen Z.

Dr. P and her colleagues couldn’t explain the abrupt increase in these acute, functional tic-like behaviors.

Dr. Pringsheim: It's not that we had never seen this in the past. But it was the scale or the magnitude of the problem that was really striking for us.

Nora: She figured there had to be some kind of external influence.

Dr. Pringsheim: Actually the first thing that we thought was that there must be something on social media. I’m in my fifties. So I went on YouTube, and I’m like, looking up Tourettes, tics, I’m not finding anything.

Ben: Ohh, you’re so old fashioned, going on YouTube. What were you looking for exactly?

Dr. Pringsheim: We were looking for viral videos about Tourette. That’s what we were looking for.

Ben: And at first, that search was a fail. Until Dr. Pringsheim brought it up at the dinner table one night with her family. And her 14 year old daughter piped up.

Dr. Pringsheim: She said, “Mom, people don't go on YouTube anymore. It's TikTok.” And I'm like, “What?” I don’t even know TikTok right? And she said, “Yeah,” and she like opened the app. And then she typed in Tourette. And it was like a jackpot. And I remember sitting there and like, my jaw was hanging open and we saw, we found thousands of videos.

[TikToker: I have no idea where this came from but I say "what a conundrum" as a tic. "What a conundrum!"]

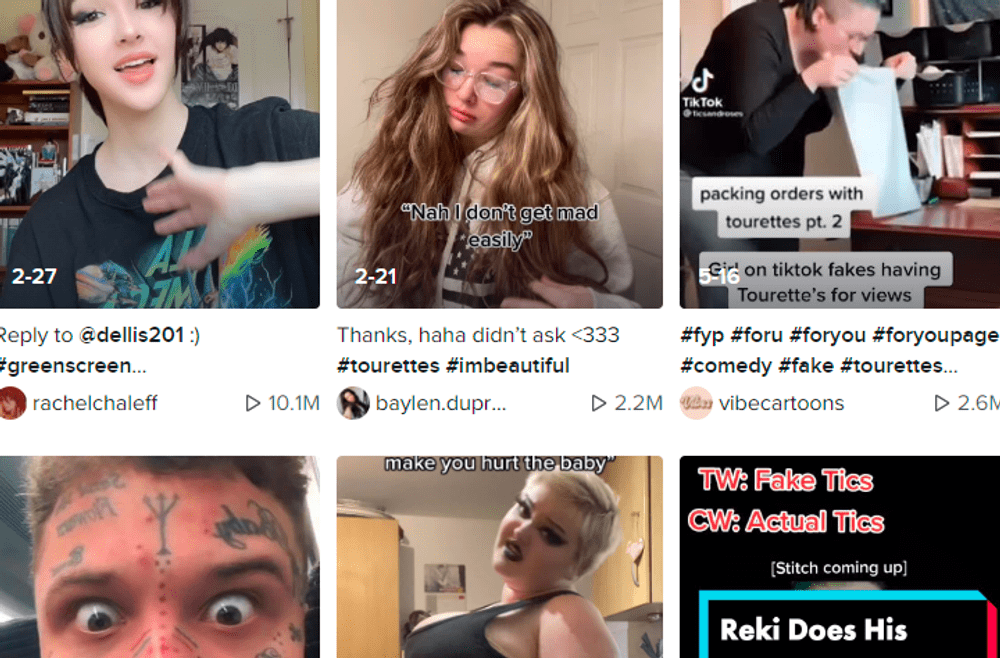

Nora: Dr. P’s teenage daughter had just opened a portal to a whole corner of the social media app known as Tourette TikTok. Where videos under the hashtag Tourettes have been viewed nearly 6 billion times.

Ben: It’s not hard to see why these have such mass appeal. A lot of the folks posting about their tics are funny and engaging. And more importantly, they’re not hiding their tics.

Dr. Pringsheim: They're not, they're not saying woe is me, you know, like I'm the most unlucky person in the world. They're saying, you know, look at me, I have these symptoms, but I'm living my life.

Nora: And they’re trying to break down stereotypes. One insanely popular creator is British TikTok star Evie-Meg Field. AKA ThisTrippyHippie.

[Evie-Meg Field: Hey guys, today I’m making sandcastles with tics. F***! Yeah. Oh, f***! No!]

Ben: ThisTrippyHippie has more than 14 million followers. One of her videos that went absolutely viral on the app? Take a wild guess.

[Field: Beans beans beans! It’s literally become part of my vocabulary.]

Dr. Pringsheim: They were all saying the word beans.

Nora: Now this did not go over well with you, did it, Ben.

Ben: Nope, not great. Not great.

Nora: I’d even go so far as to say you experienced some parental anxiety.

Ben: Yeah I think that’s right. Like my four-year-olds are not on TikTok. They’re not on, they don’t have their own Discord. They don’t have their own personal finstas. But yeah it was a little, it was scary.

Ben: To me, that's like, somewhat terrifying that a video that my kid could watch could somehow, like, trigger them into having a tic-like behavior.

Dr. Pringsheim: Yeah.

Ben: Does that make sense?

Dr. Pringsheim: Yeah, and again this is complicated, but let’s try and unpack this a little bit, in the sense that we are social creatures and we are influenced by the things that we see.

Nora: If we’re influenced by what we see, does that mean the rumors are true after all? That just watching a Tourette TikTok video can just give you a tic, out of nowhere?

Ben: Let’s let Dr. Pringsheim tell us more.

Dr. Pringsheim: Millions of people have watched those videos and never develop those symptoms. Millions of people. Right?

Ben: Right.

Dr. Pringsheim: So it's the minority of people...

Ben: Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Pringsheim: ...who watch the videos and develop the symptoms. We need to figure out who is susceptible. And that's what we're trying to do. Who can be triggered by watching these things?

Ben: We’re gonna talk more about the mystery of who can be triggered by watching TikTok tics in a few.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Nora: Okay. So a minute ago, Canadian neurologist Dr. Tamara Pringsheim was doing her level best to reassure our paranoid millennial dad Ben that when it comes to TikTok, or other social media platforms...

Dr. Pringsheim: Watching the video is not sufficient to develop symptoms. So there's clearly a vulnerability factor here.

Ben: ...and in one of her early studies of this phenomenon—published in 2021 in the journal Movement Disorders, her research team landed on some pretty big clues about who is more susceptible.

Like she said, the vast majority of patients suddenly showing up in her clinic were adolescent girls and young women. Between the ages of 12 and 25. But there was one more crucial thing they had in common…

Dr. Pringsheim: Many had underlying generalized anxiety or social anxiety disorders or depressive disorders.

Nora: There’s a lot that researchers still don’t understand about what causes Functional Neurological Disorders. Or exactly why an underlying mental health condition like anxiety or depression can put you at a greater risk of developing one.

Dr. Pringsheim: There are theories. It's not just one thing.

Ben: Dr. Pringsheim says it’s likely a mix of biological, social and psychological factors and stressors.

Dr. Pringsheim: We're trying very hard to tease this out.

Nora: But imagine you’re young. You’re having a hard time—whether you’re aware of it or not. And then, wham. The pandemic arrives. And we all know about how hard that hit the youth.

[Ayesha Rascoe: The pandemic has taken a toll on mental health and that’s especially true for teenagers.]

Dr. Pringsheim: So you add an acute stress, and it's like the straw that broke the camel's back. That it's just you reach this critical load.

Ben: For TikTok creator Adele, that straw wasn’t the pandemic. It was a devastating loss in her family that happened a few years before Covid hit.

Adele: So my mom actually passed away when I was 16.

Nora: Adele says her tics showed up not long after her mother died. And when she eventually saw her doctor.

Adele: She kind of told me like, “Oh yeah, um, you can get tics from intense trauma and things like that, an intense stress on your body”. And I'm not really a great processor when it comes to processing my emotions verbally or mentally, really. And so basically, my body took my trauma and the stress that I was under, because I was under a lot of stress at that time, and normally am. And so it took that and kind of manifested it into a physical response since I was refusing to process it mentally, so. (Laughs.)

Ben: To be clear, watching YouTube videos of other people’s tics didn’t give Adele a tic-disorder. But they were a trigger. And an outlet.

Adele: Yeah, I think my body was looking for something and that was the first thing it found, and so it, it latched on.

Nora: Adele’s story tracks with what neurologist Dr. Pringsheim has witnessed.

Just like some kids get tummy aches when they’re anxious, a small percentage of distressed Gen-Zers can be triggered by watching other people’s tics on social media.

But any tic-like symptoms they present tend to be a signal of something much deeper going on.

Ben: And this isn’t just happening in North America. We found a number of studies on this topic from around the world published just in the last year or so.

Including one from German neurologist and psychiatrist, Dr. Kirsten Müller-Vahl.

Dr. Kirsten Müller-Vahl: So in German we say Kirsten (emphasis on German pronunciation) Müller-Vahl.

Nora: Dr. Müller-Vahl has treated thousands of patients. And back in 2019—so pre-pandemic—she also noticed an influx of young people coming into her Tourette outpatient clinic, who were suffering from tic-like symptoms.

Ben: And when she interviewed them to get to the bottom of what was going on, one very popular German YouTube channel kept coming up.

Dr. Müller-Vahl: The German name is Gewitter im Kopf. Or in English, one would say ‘thunderstorm in the brain’. The influencer is a young man. His name is Jan Zimmerman.

Nora: Even if you don’t speak German, which I don’t—you can tell he’s tic-ing when his voice drops to a lower pitch.

[Jan Zimmerman: (Speaking in German)]

Ben: Jan Zimmerman has over 2 million subscribers on YouTube. He uses his platform as a window into Leben mit Tourette. Life with Tourette.

Nora: And some of his tics, like yelling “flying sharks”, in German, of course, were identical to those popping up in Dr. Müller-Vahl’s outpatient clinic.

Ben: What’s “flying sharks” in German?

Nora: (Laughs.) I think I have it right here, one second.

Ben: Uhhh…

Nora. Yeah its…Flee-GEN-de-hi.

Ben: FLEE-gen-de-HI-YAH? Alright.

Dr. Müller-Vahl: And therefore, in our opinion, it's 100 percent clear that there's a relationship between these YouTube channels and the symptomatology seen in our patients.

Ben: In Dr. Müller-Vahl’s study-the gender distribution of patients was more equal. But all patients presenting with functional tic-like behaviors had underlying mental health concerns.

Nora: However, the thing that really caught our attention about Dr. Müller-Vahl’s 2021 study in the journal Brain?

Ben: Her bold hypothesis.

Dr. Müller-Vahl: This is, as far as we know, the very first description of an outbreak of mass sociogenic illness that is spread solely via social media and via internet.

Nora: “Mass Sociogenic Illness” is a mouthful of a term for a phenomenon that used to be known as the now-unfashionable “mass hysteria”. There are mysterious incidents of MSIs documented way back in the middle ages—like those nuns at one French convent who couldn’t stop meowing.

Ben: Same, to be honest.

Nora: (Laughs.) I bark, but I don’t meow. Up to the not-so-funny Tanganyika laughter epidemic of 1962. And many more have cropped up in recent years.

Dr. Müller-Vahl: And it was clear that there's no underlying somatic disease, but it's a psychological symptom.

Ben: And here is where things get tricky. Remember my step brother-in-law, Will? Because he works in an ER, Will and his colleagues are often trying to make pretty fundamental decisions with patients that come in, because they’re met with this whole spectrum of issues with a similar wide spectrum of treatments. And one of the fundamental things they need to figure out is whether something is going wrong with someone physically, or whether it might be more psychological or emotional. Of course, it can be both. But because there’s a big branch in the road with treatment—especially for someone who just showed up in an ER—it’s an important distinction.

Nora: We should say that while experts are still hunting for a clear medical explanation of what causes these kinds of sociogenic illnesses, whatever the cause, the suffering is real.

And what makes this extra interesting to US is that in the past, these “infections” typically happened to people in the same place, often in the same social group. It was believed you had to have close proximity to the patient zero. The index case. But now?

Dr. Müller-Vahl: It seems that use of social media makes it, at least to some patients, let them have the same feeling as meeting people physically.

Ben: Meaning there can now be a virtual patient zero. Whose symptoms can spread to anyone, anywhere on the globe, who has access to the internet.

Nora: It’s too soon to tell how well Dr. Müller-Vahl’s theory about this new kind of social-media fueled mass sociogenic illness will hold up or not.

Regardless, she says most experts agree that these recent outbreaks are not Tourette Syndrome. They are functional tic-like behaviors.

Dr. Müller-Vahl: And most experts agree that there is a relationship between this new phenomenon and the videos on TikTok and YouTube.

Ben: Just like yours truly, a lot of journalists were pretty blown away by this idea. That basically videos of tics online were actually triggering tics in other people who watched those videos. And this can lead to problems in how things get reported by members of the media.

Do you remember that story from a few years back based off of a single study that suggested people were growing little horns at the base of their skull because everyone was like, craning their necks to look at their phones all the time?

Nora: I’m happy to say Ben, I do not remember that story.

Ben: Well, it was like a huge story for a week straight, Nora. Everyone freaked out. It went viral. And then it became clear that, in their breathless intensity about a story that seemed both wild and kind of believable? Because we’re all looking at our phones so much, right? Some news outlets blew the whole thing out of proportion. The study was real. The headlines, less so. And this story is similar. On the one hand…

Dr. Pringsheim: There is 100% a social media induced portion of this disorder. It’s not the whole story, though.

Ben: In Dr. Pringsheim’s view, initial news reports overemphasized social media’s role...

Dr. Pringsheim: …suggesting that that was the only cause. That, you know, your perfectly happy secure teenager could watch these videos and start tic-ing the next day, I think were sort of exaggerated. We need to understand that this is, I think, a manifestation of underlying distress.

Nora: Yeah, I’m no longer a young adult, I’m sad to say, but I am someone who has been diagnosed with anxiety and depression, and so this point was really salient for me.

The way I picture it, the youth mental health crisis—which the pandemic only made so much worse—is like the liquid hot magma simmering inside a volcano.

Ben: I think you have to say it: liquid hot magma.

Nora: I don’t want to!

Ben: I know, but like…

Nora: Fine. Liquid hot magma simmering inside a volcano. And this eruption of tic disorders is really the lava rushing down the side. Just what can you see on the surface actually.

Ben: Hmmm. So as far as these viral tic and Tourettes videos on social media go—are they the problem? Or the solution? Maybe a bit of both?

Dr. Pringsheim: It's possible that some of these videos are doing good in that, you know, it's helping people feel less alone. I think it's a double edged sword.

Nora: So, what to make of all this? Ben, I get the feeling that you’re not totally convinced by Dr. Pringsheim’s argument. That you’re actually still tempted to keep your kids off TikTok until they’ve graduated from college! Maybe longer.

Ben: (Laughs.) I guess my feelings about it were and are mixed.

Ben: I'm not trying to clutch too many pearls, right. But, like, doesn't that freak you out?

Dr. Pringsheim: Like, as a parent you mean? Or as a doctor?

Ben: I don’t—either or both. There is a form of media. That is easily accessible on the Internet….

Dr. Pringsheim: Yeah.

Ben: …that is, if consumed, affecting a portion of the population of viewers enough that they have to be hospitalized...

Dr. Pringsheim: Yeah.

Ben: ...like full stop. That to me is…what?

Dr. Pringsheim: I don't think we can escape these social influences, right?

Ben: But it wasn't happening before.

Dr. Pringsheim: But people are influenced by the people around them. like I'm thinking back to when I was in high school.

Ben: ‘Kay.

Dr. Pringsheim: It's a long time ago. But, you know, the popular girls were smoking. Other girls would start smoking, too. Right?

Ben: Who among us hasn't smoked in the bathroom?!

Dr. Pringsheim: You know what I mean? We can't escape those social influences. They're, they’re part of being human.

Nora: Both specialists we talked to seemed less interested in social media being the origin of this surge in tic disorders, and more interested in helping people suffering from them once they surfaced.

Dr. Pringsheim: You know, with appropriate diagnosis and treatment, people can get better over a relatively short period of time.

Ben: Dr. Pringsheim’s research team conducted a follow up study of their patients in Calgary. And the good news is that—six months later—most of them are doing a lot better.

Dr. Pringsheim: We found that, especially in the adolescents, there's been a lot of improvement. In some people, their tics are completely gone. Nothing nearly as as frequent or as intrusive. They've responded to cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression. They've responded to medications for anxiety or depression. I think that it's really important for patients and parents to know that there is help and that our patients are getting better.

Ben: What about those patients’ social media diet? Should they keep binging Jan Zimmerman and Tourettes TikTok? Should they stop cold turkey?

Dr. Pringsheim: I think the message here is not, you know, you should never go on TikTok.

Nora: Oh, man. We were so close to having a good reason to ban TikTok, Ben. So close!

Ben: (Laughs.) I know. But at least I can ban it in my household.

Nora: Oh you’re kids are so lucky, they’re living with a tyrant.

Ben: (Laughs.) In all seriousness though, I hope we have solved this mystery in a measured way, along with the people actually doing the science.

Tik Tok is not causing random people to have brain software glitches. But certain content on social media depicting tics might trigger tics in individuals who have an underlying mental health issue. And both of our experts say that number one, we’re probably going to see more of this spurred by social media. And number two, we need to pay attention to what is triggering these issues and treat the people who are triggered without stigmatizing them. So, fine, I will now officially stop spreading the rumor that TikTok is destroying the youth.

Nora: Maybe don’t spread that one.

Ben: (Laughs.)

Nora: And maybe also get outside and don’t spend too much time on TikTok. But if you do, and you find yourself having tic-like behaviors all of sudden, be sure to get some professional support.

Ben: Yes, absolutely. See you next week!

Nora: Bye.

[CREDITS]

Nora: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Ben: This episode was written and produced by Nora Saks. And it’s hosted by me Ben Brock Johnson…

Nora: And me, Nora Saks. Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski.

Ben: Production help and Tik Tok audio completion hilarity from Meera Raman.

Ben: Our web producer is Megan Cattel. The rest of our team is Amory Sivertson, Quincy Walters and Dean Russell.

Nora: Endless Thread is a show about the blurred lines between digital communities and Beans!

Ben: Beans!

Nora: Beans. If you’ve got an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or a wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up. Email endlessthread@wbur.org.