Advertisement

The 100-million-year origin story of laughter and humor

Resume

This is the second episode of a two-part series on the origin of jokes and humor. The story appears in podcast feeds under the title, “Jokes, Part II: Stand Up.” Listen to part one first.

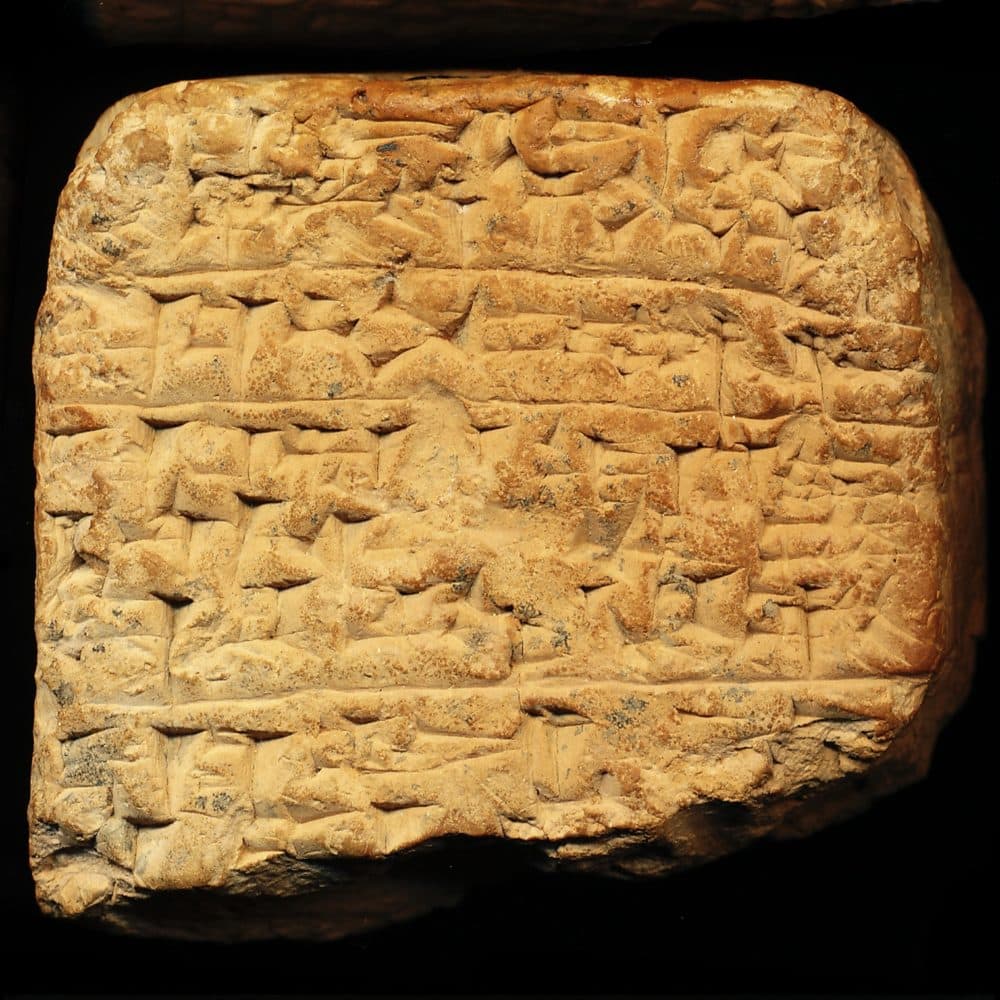

Roughly 4,000 years ago, scribes in southern Mesopotamia copied the first documented jokes in history. Written in Sumerian on clay tablets, these ancient jokes are often so rooted in a forgotten culture that their meaning has been lost. For instance, the first known bar joke reads: “A dog walked into a tavern and said, ‘I can’t see a thing. I’ll open this one.’” Hilarious, right?

As cryptic as some of these jokes can be, they offer clues into humor’s role in human civilizations. They also raise questions about when — and how — humor first emerged.

The answers to both questions are complicated and still being sorted out by historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, evolutionary biologists, and neuroscientists. Last year, two scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggested that laughter, humor’s sibling, may have begun emerging before humans 100 million years ago. Humor probably came later.

In this episode, the second of two parts, Endless Thread continues its journey attempting to deconstruct the beginnings of humor and explain an unexplainable joke from the forgotten tablets of the past.

Show notes

- The first part of Endless Thread’s two-part series, “Jokes, Part I: Sumer Funny, Sumer Not”

- Depths of Wikipedia’s tweet about “one of the earliest bar jokes” (Twitter)

- Chimpanzees (North Carolina Zoo)

- Evolution, Structure, and Functions of Human Laughter (The Handbook of Communication Science and Biology)

- Play vocalisations and human laughter: a comparative review (Bioacoustics)

- The mystery of what makes a joke funny — but only to some people (The Conversation)

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Ben Brock Johnson: Hey folks, you’re listening to Part II of our story on the origin of jokes and humor. If you missed the first episode, go back and listen to that. Or don’t, but you may not get the joke. Anyway, enjoy the show.

Amory Sivertson: Last time on Endless Thread …

Ben: So can you read it for us?

Seraina Nett: In Sumerian?

Ben: Would love that.

Seraina: So in Sumerian it reads: “ur-gir-re ec-dam-ce in-kur-ma ...”

(Scene change.)

Seraina: In English, that means something like, “A dog entered into a tavern. And he said,” — probably — “‘I cannot see anything. I shall open this,’” or “‘this one.’”

(Scene change.)

Dan Mauzy: I don’t get it. I don’t get it.

Quiana Scott-Ferguson: What can a dog open? They don’t have thumbs.

(Scene change.)

Ben: So we’re blasting down the highway. Amory’s behind the wheel.

Amory: What are we doing next?

Ben: I don’t know, you tell me. What are we doing next?

(Scene change.)

Philip Jones: (Door opens.) This is the tablet room.

Amory: Oh, wow.

(Scene change.)

Ben: So you’re team “Not Joke?”

Phil: I’m team “Humorous Sayings.” So maybe we’re talking Seinfeld rather than Bob Hope.

Ben: OK. I like it.

(End of montage.)

Dean Russell: Ben. Amory.

Amory: Dean Russell.

Ben: D. D-dog.

Dean: Do either of you know what a baby chimpanzee is called?

Ben: An imp.

Amory: A chimpling. A chimpette.

Dean: It’s a very technical term. It’s called a chimp off the old block.

Amory: Ah!

Ben: Ah, Dean! We walked right into that one.

Dean: So, yeah, I have—. The humor from last episode has not improved.

Ben: No, you’ve converted it all from dog humor to chimp humor.

Dean: It’s evolved.

Ben: It’s—. (Laughs.)

Dean: Anyway, I promise that is my one-and-only joke. The reason I bring you this terrible chimp joke will become clear in a moment. That reason starts, though, with the big questions from the last episode. (1) What does the Sumerian dog-in-a-bar joke mean? (2) And why does it matter? Why do so many people online and in academia — why do so many care about confirming that it’s a joke and solving its meaning?

Ben: Yeah, because we want to know why we all think it’s a joke, right? There’s something about it that feels universal, which feels like a good joke. And there’s meaning in that universality.

Dean: Yeah. And so something both of you said last episode, something we heard from Phil Jones, the guy at the Penn Museum, was that this bar joke is likely one of the first documented examples of humor. And if we can firmly establish that the bar joke is, you know, a joke and sort out what makes it funny—.

Ben: Which, I feel like we did a pretty good job of.

Dean: True. Sort of. True. Yes. But let’s say if we can firmly settle those things, that gives us a clue about how we humans came to be the people we are today. It gives us some sense of the role humor has played in our development into what I would argue is a pretty unique species.

Ben: And boy, do we need some of that human humor these days.

Dean: We do. So, for this part of the story, I’m going to do my best to bring all of these things together and firmly answer those questions. What’s it mean? Why’s it matter? So we get at this greater meaning. And our extremely circuitous mystery is going to go a little bit more bananas and—.

Amory: A-oh!

Dean: Sorry.

Amory: You said the jokes were done. I’m keeping a sharp eye out— ear out. I’m ready.

Dean: Ready? Here we go. We’re going further back than Sumer, further back than tablets, further back than people. We’re to the dawn of the apes.

Amory: I’m Amory Sivertson.

Ben: I’m Ben Brock Johnson. And you’re listening to Endless Thread.

Amory: We’re coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station.

Ben: Today’s episode: the second of two parts, in which producer Dean Russell helps us deconstruct the origins of humor and explain an unexplainable joke from the forgotten tablets of the past.

Dean: “Part II, Jokes: Stand Up.”

(Chimpanzees scream.)

Jennifer Ireland: So those are excited chimps. And it’s probably because they heard me over here. (To the chimpanzees.) Hi, Ruby girl. How’s my best girl? (To Dean.) So you see the chimp who was kind of making the duck face at me? That’s Ruby.

Dean: And this is Jenn.

Jenn: She always greets me like that when she sees me. (To Ruby.) Hi, Ru. Hu-hu-hu-hu-hu-hu-hu. That’s my girl. (Laughs.)

Dean: Jennifer Ireland’s in charge of the mammals at the North Carolina Zoo, which is this enormous zoo directly in the middle of the state. A few weeks ago, Jenn took me to this half-acre forest with rolling hills and arboreal jungle gyms and, mysteriously, a fake termite mound. Just a surreal little plot where the chimpanzees live.

Jenn: So, in this habitat, I don’t know how many chimps are out here today. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven. Should be about nine chimps out here today. And in front of us, we have Genie, who is in the back. She has a really dark face. We have Lance here on the left.

Dean: And the reason I’m here — and by here, I mean at the top of this helix staircase, looking down at chimps named Ruby and Genie and Lance and Obi, who’s this cute toddler chimp doing cartwheels — the reason I’m here is because I’m trying to figure out how this Sumerian joke came to be.

(Chimps scream.)

Amory: OK, so why are we talking about chimps?

Dean: This is kind of me rabbit-holing because my initial reading into the origin of jokes sent me into reading about the origin of humor, which sent me into reading about the evolution of laughter. And so, we’re going to start there, at the bottom of the rabbit hole: Where does laughter come from?

I had this idea that maybe laughter started as a cultural thing, maybe even started with the Sumerians. Maybe that’s why they have the first documented jokes. But then, when I looked into it, I learned something that I didn’t know. I learned that laughter is not a human-only thing.

Jenn: Yeah, chimpanzees definitely laugh. Usually, when they laugh, there has been some sort of physical contact. They will tickle each other. They’ll pinch each other. They’ll wrestle each other. So they are laughing all the time when there’s that type of physical contact.

Dean: To me, this fact was kind of mind-blowing. Chimps — which share 99% of our DNA — they have a funny bone.

Jenn: Chimpanzees laugh a little different than humans. Humans, when they laugh, it’s all on the exhalation, right? When we’re laughing, it’s all the noises coming out. Chimpanzees, their laugh is on the inhalation and the exhalation, and it’s kind of a panting sound. So it sounds kind of like huh-huh-huh-huh-huh-huh-huh.

Chimpanzees: Huh-huh-huh-huh-huh-huh-huh.

Dean: So, Ben and Amory, I just Slacked you this video.

Amory: Oh, my god. What is going on? Was one of them breathing into the person’s— chimp’s mouth?

Ben: To me it looks like a parent over a juvenile, and they’re being silly together. That’s what I’m seeing.

Dean: There are two chimps here, named Kendall and Tammy. They’re in a rugby huddle, bent over at the waist, and they’re tickling each other.

Amory and Ben: Ohhhhhhh.

(Chimps laughing continues.)

Dean: This odd panting-laughter is their way of saying, “Oh, my god. This is fun.”

Jenn: Not only can you hear them laughing, but you can see Kendall’s mouth, and you can see that his mouth is wide open. And so he’s got a big play-face on. That’s just another way to communicate, “I love what is going on. Not only my laughing, but my face is telling you how happy I am and how much I am enjoying this interaction.”

Dean: Laughter is also called a play vocalization in scientific circles. There’s a theory that it evolved from heavy breathing, which, maybe, Amory, that’s what you’re referring to. It sounds like heavy breathing. And it’s a really crucial communication and bond-building tool, like with this tickling. And it’s also an extremely effective tool for learning.

Ben: What do you mean?

Dean: You know how when you’re a kid, and you’re roughhousing but also giggling?

Ben: Why? You mean when you’re a kid? I’m still doing that.

Dean: (Laughs.) Chimps do this same thing, especially when they’re young. They play-fight, which is extremely important because it trains a youngin on how to defend themselves. And biologists have actually done tests and found that in certain groups, play-fighting can turn into real fighting if one of those youngins don’t have a voice box, meaning they can’t laugh.

Ben: Whoa.

Dean: Yeah, exactly. They can’t communicate that it’s all good fun, and so it kind of escalates into real fighting. So you need laughter. And it also encourages the learning to keep going because it’s something that’s fun, so you’ll keep doing it.

Ben: See, this makes total sense to me as a dad, I will say. I roughhouse with my kids all the time, and the way that I can tell whether or not — because I'm so much bigger than my kids — and the way that I can tell whether or not they are playing well together and whether or not I’m playing well with them is completely auditory, I would say, almost completely auditory. You know? Because you’re listening for the way people react, and if they’re squealing with joy versus squealing with pain, there’s a difference there, an audible difference.

Dean: Ultimately, what we’re talking about here is non-language communication, right? So, Amory, you asked the question, “Why chimps?” I started with chimps because they are the closest cousin species with humans. We share a common ancestor from about 8 million to 6 million years ago. Because we both laugh, this actually suggests to scientists that laughter precedes humans. It is probably also at least 6 million years old.

Amory: Hmm.

Ben: Whoa.

Jenn: Chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans are all apes. We’re all related to each other, and laughter seems to serve the same purpose in every one of those species.

But the wild thing to me is that laughter may actually be even older. Last year, these two UCLA scientists, they documented play vocalizations — these proto-laughs — in 65 species. Apes. Monkeys. Black bears. Rats. Seals. They all vocalize during play. And this suggests that the first laugh — the first laugh ever — that may have come from a common ancestor 100 million years ago.

Ben: Whoa.

Amory: Wow.

Ben: Are you saying that the thin lobe-finned fish was cracking up when it came out of the muck? “Hey, I’m almost walking here.”

Dean: (Laughs.)

Amory: I don’t get it.

Dean: I thought it was good.

Amory: Oh, I do get it. Never mind.

Ben: Jesus Christ.

But, Dean, when you started, you mentioned humor, which I feel like is more complicated and more to the point of the Sumerian joke. Humor, in my mind, is more of a story that causes laughter — or an idea. It’s less like tickling but more like an intellectual presentation that people — that animals — react to.

Dean: Yeah. So, for this, I’d like us to think about a moment in Seinfeld. Ben, as you know, I’ve been working my way through Seinfeld recently. And as I was writing this story, I landed on this one episode where Kramer goes to see chimpanzees.

[Cosmo Kramer: I stopped to look at the monkeys when all of a sudden I am hit in the face with a banana peel. I turn and look, and there is this monkey really laughing it up.]

Amory and Ben: (Laughs.)

Dean: All right, I’m going to say, setting aside the fact that Kramer refers to chimps as monkeys, which is not true, chimps have actually done stuff like this. They’ve thrown feces at zoo guests, and they’ve had the same semi-laughing reaction. And what I want to know from you two is: Would you call that humor?

Ben: Would I call hitting one of your jailers with your own excrement humorous? Yes, I would.

Amory: (Laughs.) I mean, it’s all humor. There are just different kinds. Would I call it witty? No. But it’s definitely got some quality slapstick potential there.

Ben: Well, you know what’s interesting too is I think the perspective matters. So it may not be humor to the person who got hit with the excrement or the chimp throwing the excrement. But if another chimp witnesses it and is not involved in the action, but that is them witnessing the story, that feels more like humor, if that makes sense.

Dean: Mm-hm. Yeah. So with that in mind, I have one more video for you all to watch.

Ben: Oh, I’m looking at a single chimp sitting on top of this little platform. And the chimp is next to a big old pile of hay.

Amory: Yeah, tossing some hay into a pile of hay.

Ben: Someone’s reacting. Someone’s kind of laughing. Oh!

Amory: Oh!

Ben: There’s another monkey under the pile of straw.

(Chimpanzees make noise.)

Amory: They’re not monkeys, Ben. They’re chimps.

Ben: I’m sorry, they’re chimps. There’s another chimp under the straw.

Amory: There’s a chimp hiding.

Ben: Oh, and they’re all having a great time about it.

Amory: But the one that popped out of the straw was clearly laughing and knew that there was a joke being played here.

Ben: That was the Ben of the bunch laughing at its own joke.

Amory: (Laughs.)

Dean: I thought it was pretty interesting to compare this to the Sumerian joke. Because to me, it has a very similar structure, right? You’ve got the set-up: Terry is hanging out near some hay. That’s setting an expectation. Then Ruthie, who is hiding in the hay. She sits up and breaks your expectation. And that’s the punchline.

Ben: Yeah.

Amory: OK. I buy it.

Dean: Would you describe it as humor?

Jenn: You know, it’s kind of hard to say what’s funny to a chimp and what’s funny to a person. You know, it’s the whole, did someone slip on a banana peel? Do they find that funny?

Dean: I was pretty excited by this video because I saw this as chimps laughing at chimp comedy. I was thinking, no way is this Sumerian joke one of the first jokes. Maybe the first joke is actually 100 million years ago.

But Jenn, she was like, “Mmmm, no.”

Jenn: They’re not really laughing, but a pant-grunt is kind of a greeting, a really positive vocalization. And I think that part of that, spurred on by the reaction of the keepers in the video because they’re all laughing, and they’re all like “ahhhh.”

(Keepers laugh. Chimps pant-grunt.)

Amory: You know this is humor, no doubt. But I wasn’t thinking about this as a joke. I guess I have associated the word “joke” more with words. This feels like a prank, which maybe some people would say they’re the same thing. But I guess to me, I would not call the Ruthie–Terry scenario a joke. But it is humorous. It is humor.

Dean: So, I mean, when I saw this, I was like, “This is humor for sure.” But the difference here is that the chimps, themselves, are not actually laughing. It sounds like laughter, but it’s a pant-grunt. There’s a subtle difference. These chimps are putting on a show for the zookeepers. And when the keepers laugh, the chimps get really excited, then pant-grunt, they don’t laugh. The similarity here is: Think about all those apes you’ve read about who have sign language, who use sign language.

[National Geographic narrator: Dr. Patterson claims Koko has a working vocabulary of about 450 signs …]

Dean: They learned it from humans. They don’t sign with other apes in the wild. And it’s the same thing here. If you want to call this a joke, that’s fine. Or if you want to call it humor, that’s fine. But it doesn’t indicate that jokes are millions of years old like laughs. Because things like this only happen when the chimps are interacting with humans. They learned it from humans. This suggests that humor is a purely human development.

Ben: Whoa.

Amory: I’m not going to ever get used to that. But I’m guessing we will learn more from Dean as we go along here.

Dean: Yup. We’ll get to more in a minute.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Sophie Scott: People always send me emails and pictures of orangutans when I say this, but I have looked into the literature quite deeply, and as far as I can see, there is no good evidence for animals in the wild, mammals in the wild, primates in the wild showing anything that looks like humor.

Amory: Who’s this?

Dean: After getting a handle on where laughter comes from, I called Sophie Scott, a neuroscientist at University College London, because I wanted to understand: How did humor come about?

Sophie: It certainly makes me realize a lot more about my own laughter. So if I’ve noticed that, like, I have a relative who’s always laughing. I really found her laughter very irritating. She laughs so stupidly; look at her stupid laughter. And working with the laughter made me realize, actually, there was nothing whatsoever strange about her laughter. What was odd about it was that I didn’t join in, and I don’t join in because I don’t like her.

Amory: Oh man, Sophie is a woman after my own heart. (Laughs.)

Dean: Yeah. Sophie really helped me understand this Sumerian joke. Because she’s written about ancient humor among other things. She’s written about Sumerian jokes and Egyptian jokes. And she told me Romans were really into crucifixion humor for some reason.

Sophie: So there’s one joke about two Romans walking along, and they look up to see a popular athlete who’s been crucified. And one of them says to the other, “Oh, he’s really flying now.”

Dean: Oh, my god. Wow.

Sophie: I know, I know.

Ben: I don’t get this joke.

Amory: (Laughs.) All right, maybe Sophie and I are not as akin as I thought.

Dean: I swear, I thought you guys were going to find that Roman thing funny.

Amory and Ben: (Laughs.)

Dean: But I guess, despite that, she really does know a lot the mechanics of laughter and humor.

Sophie: Right from the outset, there are things that will make human babies laugh that don’t make other infants laugh. And those are nonphysical things, like playing peekaboo or talking funny. So again, actually, babies, humans are able to pick up on someone’s playful intentions without touch being involved.

Amory: Peekaboo is considered nonphysical comedy?

Dean: Yeah, in the sense that there’s no person-to-person touching involved. Non-human laughter is based on that really close contact. But humans are different in that we laugh when talking with each other and watching a performance. Essentially, we laugh at stories. And we tell these stories — funny stories, a.k.a. jokes — in part, because laughing feels good.

Sophie: You also see an increased uptake in the naturally circulating endorphins, and that’s your body’s natural painkillers. And you see that when you’ve been laughing, which is one of the reasons why you get a nice, warm, buzzy feeling when you’ve been laughing. It’s exactly the same as if you’ve been exercising.

Dean: Human social bonding is partly based on endorphins. So the stuff that makes us feel close is often the stuff that fuels those endorphins, like singing together, eating together, dancing together, and especially laughing together. So if I tell a stranger a joke and we both laugh, we’re biologically building a bond. And, I mean, think about how much time you both have spent laughing together. Amory apparently does not even need the jokes to be done, to be finished, to start laughing.

Amory and Ben: (Laughs.)

Ben: OK, let’s hear it.

Amory: What do you call a blonde— (Laughs.)

Ben: Apparently, this joke is hilarious.

Amory: OK, I want to go back to the chimps for a second because it sounds like they bond through laughter, too, but that laughter happens in very close quarters with tickling and play-fighting. So the difference is what?

Dean: Right. They’re not telling stories like the Sumerian joke to make each other laugh and bond.

Amory: Is that because they don’t have the same kind of language that we do?

Dean: Partially, yeah. But maybe not in the way you're thinking. Now, I’m going to take some sharp turns here, so bear with me.

Amory: (Laughs.) Buckle up.

Ben: Hold onto the handle above the door? OK. We’re ready.

Dean: Sometime after that 8 million to 6 million year split between the chimp line and human line, humans’ — or protohumans’ — brains started to change. They became more complex. And you can see this in how laughter happens in our brains today. Because, neurologically speaking, humans have two different laughs.

Sophie: Think about the last time you started laughing, and you could not stop laughing, you know, really involuntary laughter. You may be desperately trying to stop it, but you can’t stop. That is a different kind of laughter, and it seems to be based in different brain areas than laughter, which to some degree is, for want of a better phrase, volitional.

Ben: Involuntary and volitional? Is this like a real laugh and a fake laugh?

Dean: Not exactly. It’s more like an involuntary crying belly laugh, which is kind of rare—.

Amory: I’m sorry, Ben, you should know this. This happens to me every single tracking session we do where — we probably have so many of these on tape — where for whatever reason, all of the sudden, I cannot keep it together. And I’m trying to, but I cannot.

Dean: Exactly.

Ben: She gets the giggles. You can’t stop her.

(Montage of Amory’s laughing outtakes.)

Dean: So there’s that kind of laughter, and then there’s every other kind of laugh that humans exhibit. An involuntary laugh is literally one that you can’t control, as Amory described. You’re rolling on the floor. Whatever. A volitional laugh is not something you necessarily intend to do or fake. It’s voluntary in the sense that you could stop it in the middle of the laugh if you had to. Or you could stifle a laugh because you’re at a funeral or something like that. This is most of our laughter.

Ben: So you’re saying even when someone tells you a joke, unless you’re Amory, it’s probably a volitional laugh?

Dean: Right. Or a mix of both. The reason I bring this up is because these two laughs travel different pathways in the brain. Belly laughs — Amory laughs — follow this one pathway through the middle of your brain, one that goes through a region for involuntary functions.

Sophie: Now, that is evolutionarily older. We share that with all other mammals, and it’s associated with much more reactive vocalizations often that are more emotional and sort of automatic.

Dean: This is how chimps laugh. Their brains have the same pathway. But a volitional laugh goes through something called the lateral motor area, which is only in humans.

Sophie: And that’s something I’m using right now when I talk. It’s something you don’t find in other primates, and it’s associated with voluntary control over all over our bodies. So humans aren’t only able to talk because they’ve got the right vocal tract, they’ve also got a brain that can control the vocal tract.

As Sophie says, this evolved brain pathway for human-only laughs, it is the same pathway that we use for controlling speech, for complex language, for storytelling, for joke-telling; which means that it is possible — maybe even probable — that just as humans were developing the ability to tell jokes, they were simultaneously developing the ability to laugh at those jokes.

So what does this tell us about why the Sumerian joke matters? I’m going to take us back to the Penn Museum and Phil Jones.

Ben: So how old is this?

Phil: This is just under 5,000 years old.

Dean: As far as we know, Homo sapiens are the only living species that can talk about things we have never seen, touched, smelled, or experienced. It’s unclear when exactly this first came about. Some evidence suggests 100,000 years ago, some suggests 35,000 years ago. But somewhere in there, humans began to tell fictions and myths and stories …

Ben: … The tablet over here on the left, like the one that, you know — I didn’t read it yet, but it says “Gilgamesh” on the description of it — you know, that one is beautiful and tiny and complex …

Dean: … and we told proverbs …

Phil: “A dog knows, ‘Take it.’ It does not know, ‘Put it down.’”

Dean: … and we told jokes.

Phil: “So a dog came to a brothel and said, ‘One does not see anything. Let me open this one.’”

Dean: And historians have suggested that it’s our ability to tell all of these fictions that allowed humans to expand their social groups from the small-sized troops that chimps have — which is 20 or so — to literally millions of people. Religions and cities and nations.

Amory: Like Sumer.

Dean: Yeah, because Sumer was just a collection of disparate people who, several tens of thousands of years earlier, would have nothing to do with each other. But our fictions can travel and shape our ideals and cultures and bring small troops of people together into giant communities. For instance, to know that someone else — maybe someone you’ve never met — to know that they find a story funny that you find funny, that’s an instantaneous sign that we’re on the same team, the in-group. And if they don’t share your fictions, then they’re in the out-group.

And so Sumer comes after this cognitive leap, out of the agricultural revolution, which produced so much food that in 3500 B.C.E., it became hard to keep track of it all.

Ben: … It’s interesting to read this description and and have it be like we invented writing because people couldn’t remember …

Dean: So, as Phil told us, Sumerians invented writing, first to count clay pots filled with food. Then they realized they could record more complex ideas. They started to set their fictions in stone and clay so that they could travel geographically and through time.

This Sumerian joke from the dawn of writing matters because it is documented evidence of this moment. It is one of the first instances in which a fiction was written down. Its meaning passed to another person would read it and laugh, and their endorphins would jump. They would feel a connection with their community, their Sumerian/Babylonian culture in which this joke was rooted. It’s like reading a joke on a subreddit and thinking, “This community gets me.” Except that it happened several thousand years before the internet.

Ben: But, Dean, what did all of this tell you about the meaning of this joke? A dog walks into a bar and can’t see a thing and opens “this one.” What did all of this tell you about why that’s funny?

Dean: Yeah. What all of this told me is that this joke is not funny. Not to us. And no matter what we do, it never will be. I mean, Phil and his theory about the watchdog who opens the front door of the brothel, he might be right. But so could anyone else.

We just don’t know because Sumerians/Babylonians, they’re the in-group. We’re on the outs. We were never meant to find it funny. And as Sophie Scott, the neuroscientist, told me, that’s OK.

Sophie: (Laughs.) It’s fantastic, isn’t it?

Dean: Why do you say that’s fantastic?

Sophie: Well, because it’s so obviously a joke. But also, what? Why? Why was that funny? What did those words mean that we are getting from the translation? It’s like a whole world being opened up of possible meanings. And the sort of — this tantalizing fact that you’re almost certainly never, ever going to know why that was funny. It’s amazing.

Ben: I mean, it’s sort of mind-blowing to think about how jokes and laughter are not actually forever-things. You know, these are things that came into the world. And also — even though the words are not the same derivative, which we looked up at one point — the idea that humor is potentially something uniquely human, that is kind of amazing to me. I don’t generally buy into the whole “humans are special.” I don’t really buy into that in general, you know? But if you tell me humans are special because we can make jokes, then OK.

Dean: You can get on board.

Ben: I can get on board with that.

Amory: I mean, I also love this, but I feel like Sophie’s conclusion of—. It’s like next-level you-had-to-be-there. You know what I mean? Like you had to be there at that time in order to understand the joke in the way that they meant it. And we’re doing that all the time with our sense of humor. And that’s frustrating when you’re trying to understand something of the past, but it’s also kind of—

Ben: Special?

Amory: Yeah, yeah. We’re constantly creating little time capsules that will be maybe found and maybe understood or maybe not in the future.

Ben: Speaking of which, you guys have told me — you guys keep reminding me that chimps are not monkeys. But I haven’t told you this thing this whole time, which is that my brother almost adopted a chimp.

Dean: Whoa.

Ben: Yeah.

Amory: What?

Dean: Whoa.

Ben: I thought I was going to be a monkey’s uncle.

Dean: Oh!

Amory: Oh, my god. Oh, my god.

Ben: (Laughs.)

Dean: Wow. Amazing.

Amory: (Laughs.) How long have you been holding on to that one?

Ben: At least three minutes.

[CREDITS]

Amory: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Ben: Want early tickets to events, swag, bonus content? My full repertoire of ape jokes? Footage of Amory’s laughing fits? Join our email list! You’ll find it at wbur.org/endlessthread, where you can also see pictures and those videos from our Sumerian–chimpian adventures.

Amory: This episode was written, reported, and produced by Dean Russell and co-hosted by me, Amory Sivertson…

Ben: And me, Ben Brock Johnson. Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski. Our web producer is Kristin Torres. The rest of our team is Nora Saks, Quincy Walters, Grace Tatter, Megan Cattel, and Paul Vaitkus.

Amory: Endless Thread is a show about the blurred lines between digital communities and a couple of stinky chimps rollin’ around in some hay. If you’ve got an untold history, an unsolved mystery, or a wild story from the internet that you want us to tell, hit us up. Email Endless Thread at WBUR dot ORG.