Advertisement

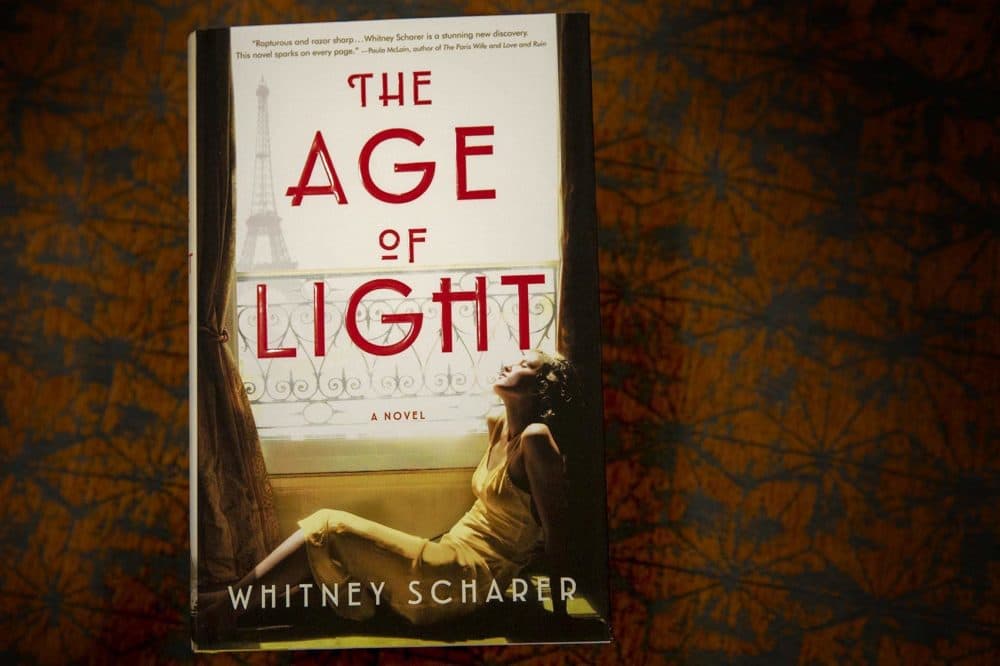

Life Of Photographer Lee Miller Illuminated In 'The Age Of Light'

Resume

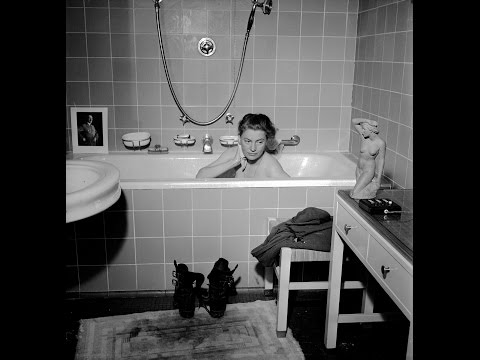

You may have never heard of Lee Miller.

Author Whitney Scharer's debut novel, "The Age of Light," is based on the life of Miller, who went from fashion model and muse of photographer Man Ray, to her own career as a studio photographer and one of the few accredited female war correspondents to cover World War II.

"I was initially drawn to her confidence and ambition. I just found her to be this incredibly modern woman," Scharer says. "But as I learned about her, what I was most taken with, was this fragility that was underneath the surface of her confidence, that came from all of these traumas that she endured in childhood and all of the subsequent objectification by men — her father, fashion photographers, Man Ray, and that I think is what makes her such a complex and interesting character."

Although "The Age of Light" is not a biography, Scharer dives into the real relationship between Miller and Ray, a much older and famed photographer, and the traumas that Miller endured from childhood into her adult years. Scharer says Miller suffered from undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder.

"She was an alcoholic. She was probably clinically depressed, and she was just a woman who had such ambition and such potential. And then you kind of see her life narrowing at the end," Scharer says.

But, as Scharer points out, Miller remains an inspiration to other female photographers, writers and artists, showing it's possible for women to carve out space for themselves in a male-dominated field.

"I really connected with Lee very deeply in her desire to make space for her own work," Scharer says.

- Here are more photos of Lee Miller and Man Ray, and Miller's photography portfolio

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "The Age of Light"

Interview Highlights

On Man Ray and Miller using each other's work

"They were constantly writing their names on prints that the other made. And both of them were quoted as saying, 'Oh, it didn't matter who took the pictures. We were working so closely together in the dark room that his work could have been my work, and her work could have been his work.' That's all well and good, except that Man Ray was the one who was getting most of the credit for that work, which I think is a little problematic."

On Miller's struggle to get out from behind Ray's fame

"She became more and more frustrated throughout their relationship, both by being eclipsed by him and also by his increasing jealousy. You know, he talked about how he wanted her to be young and free, and what he really wanted was for her to commit to being with him for the rest of her life, which she wasn't prepared to do."

On the effects that Miller's childhood trauma had on her

"I think that the war was this final trauma that came on top of all of these other traumas that she'd experienced in her childhood. ... After the war, she did try to continue doing photography for a while. She moved back to England and was still working as a correspondent for Vogue. But it kept getting harder and harder for her to do it, and eventually she actually boxed up all of her negatives and photographs and literally hauled them up to her attic and never talked about them. She had one child — her son Antony Penrose — and he wasn't even aware that his mother was a photographer until practically the time of her death. She just never, ever spoke about it."

"I really connected with Lee very deeply in her desire to make space for her own work."

Whitney Scharer

On Miller and Ray reconnecting decades after their breakup

"In real life, Lee Miller and Man Ray had this tempestuous relationship for about three years. They completely lost touch because the breakup was very painful and terrible for both of them. … But right after World War II, she and Man Ray reconnected. They didn't see each other very often. By that point, he was living in Los Angeles. She was living in London. But they corresponded by letter and Man Ray sent her gifts.

"At the end of their lives, there was a retrospective of Man Ray's work. And I believe Lee was asked to speak at that. In any case, she went there and met up with Man Ray. And there's this amazing story that I had wanted to include in my book, but it didn't end up fitting, but where they found each other at the exhibit. And apparently, there was this giant cardboard storage tube lying on its side, that I guess the sculpture had been sent in or something, and Man Ray — old, infirm — crawled in one end of it and shouted for Lee to crawl in the other end and then they met in the middle. I just find that so beautiful."

On writing her first book

"I found myself at first feeling like Lee and I were not very similar because she was this beautiful model, who on the surface seemed to have this perfect life in many ways. And then as I got to know her and I realized actually, it wasn't perfect, that she had experienced this trauma in her past. I also haven't had that happen to me either. But as I was thinking about her so deeply over these years, what I did really connect to with her was her artistic journey. And as a woman writer, I have spent my whole life not feeling able to call myself a writer until now that I have this book coming out. And I think that that's something that women writers and artists experience all the time, that we don't feel like we sort of deserve to take the space to make our art. I'm not sure why that is, but I definitely felt that, and other women writers that I know feel it as well."

Book Excerpt: 'The Age Of Light'

by Whitney Scharer

The night Lee meets Man Ray begins in a half-empty bistro a few blocks from Lee’s hotel, where she sits alone, eating steak and scalloped potatoes and drinking half pitchers of dusky red wine. She is twenty-two, and beautiful. The steak tastes even better than she thought it would, swimming in a rich brown roux that pools on the plate and seeps into the layers of sliced potatoes and thick melted slabs of Gruyère.

Lee has passed the bistro many times since she arrived in Paris three months earlier, but — her finances being what they are — this is the first time she has ventured inside. Dining alone is nothing new: Lee has spent almost all her time alone since she got here, a hard adjustment after her busy life in New York City, where she modeled for Vogue and hit up the jazz clubs almost nightly, always with a different man on her arm. Back then, Lee took it for granted that everyone she met would be entranced by her: her father, Condé Nast, Edward Steichen, all the powerful men she had charmed over the years. Those men. She may have captivated them, but they took things from her — raked her over with their eyes, barked commands at her from under camera hoods, reduced her to pieces of a girl: a neck to hold pearls, a slim waist to show off a belt, a hand to bring to her lips and blow them kisses. Their gaze made her into someone she didn’t want to be. Lee might miss the parties, but she does not miss modeling, and in fact she would rather go hungry than go back to her former line of work.

Here in Paris, where she has come to start over, to make art instead of being made into it, no one pays much attention to Lee’s beauty. When she walks through Montparnasse, her new neighborhood, no one catches her eye, no one turns around to watch her pass. Instead, Lee seems to be just another pretty detail in a city where almost everything is artfully arranged. A city built on the concept of form over function, where rows of jewel-toned petits fours gleam in a patisserie’s window, too flawless to eat. Where a milliner displays exquisitely elaborate hats, with no clear indication of how one would wear them. Even the Parisian women at the sidewalk cafés are like sculptures, effortlessly elegant, leaning back in their chairs as if their raison d’être is decoration. She tells herself she is glad not to be noticed, to blend in with her surroundings, but still, after three months in this city, Lee secretly thinks she has not seen anyone more beautiful than she is.

When Lee has finished the steak and sopped up the last of the gravy with her bread, she stretches and sits back in her chair. It is early. The restaurant is quiet, the only other diners elderly Parisians, their voices too low for eavesdropping. Empty wine pitchers are lined up neatly next to Lee’s plate, and on the far end of the table is her camera, which she has taken to carrying everywhere despite its heaviness and bulk. Just before she boarded the steamer to Le Havre, her father pushed the camera into her hands, an old Graflex he no longer used, and even though Lee told him she didn’t want it, he insisted. She still barely knows how to operate it — her training is in figure drawing, and when she moved to Paris she planned to become a painter, envisioned herself dabbing meditatively at a canvas en plein air, not mucking about with chemicals in a suffocating darkroom. Still, Lee has learned a bit about taking pictures from him and at Vogue, and there’s something comforting about the camera: both a connection to her past and something a real artist might carry around.

The waiter stops by and takes her empty plate, then asks if she’d like another pitcher of wine. Lee hesitates, picturing the dwindling francs in her little handbag, then says yes. Even though her savings are getting low, she wants a reason to stay a little longer, to be surrounded by people even if she is not with them, to not go back to her hotel room, where the windows are painted shut and the trapped air always smells oppressively of pot roast. Lately she’s been spending more and more time there, drawing in her sketchbook, writing letters, or taking long afternoon naps that leave her unreplenished — anything to pass the time and make her forget how lonely she feels. Lee has never been very good at being by herself: left to her own devices, she can easily sink into sadness and inactivity. As the weeks have passed, her loneliness has gained heft and power: it has contours now, almost a physical shape, and she imagines it sitting in the corner of her room, waiting for her, a sucking, spongy thing.

After he has picked up her plate, the waiter lingers. He is young, with a hint of mustache above his lip so faint it could have been penciled there, and Lee can tell he is intrigued by her.

“Are you a photographer?” he finally asks, the word almost the same in French as in English, photographe, but he mumbles, and Lee’s grasp of the language is still so rusty it takes her a moment to parse his question. When she doesn’t respond, he tips his head at the camera.

“Oh, no, not really,” Lee says. He looks disappointed, and she almost wishes she said yes. Since she’s been here, Lee has taken a few pictures, but they have been shots any tourist would attempt: baguettes in a bicycle basket, lovers pausing to kiss on the Pont des Arts. Her initial tries did not go well. The first time, when she got the prints back from the little camera shop around the corner, they were entirely black; Lee had somehow exposed the plates to light before they were developed. The second set — made with more care, the plates inserted into the camera gingerly, a light sweat dotting her upper lip — came back as murky gray masses, so blurry they could have been clouds or cobblestones, but certainly not close-ups of the sculptures in the park she had been shooting. Her third set of prints, though, was actually in focus, and looking at those small black-and-white images, conjured not only from her mind but from a unique combination of light and time, Lee filled with an excitement she never felt when painting. She had released the shutter, and where nothing had existed, suddenly there was art.

Excerpted from THE AGE OF LIGHT by Whitney Scharer. Copyright © 2019. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Emiko Tamagawa produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on February 19, 2019.