Advertisement

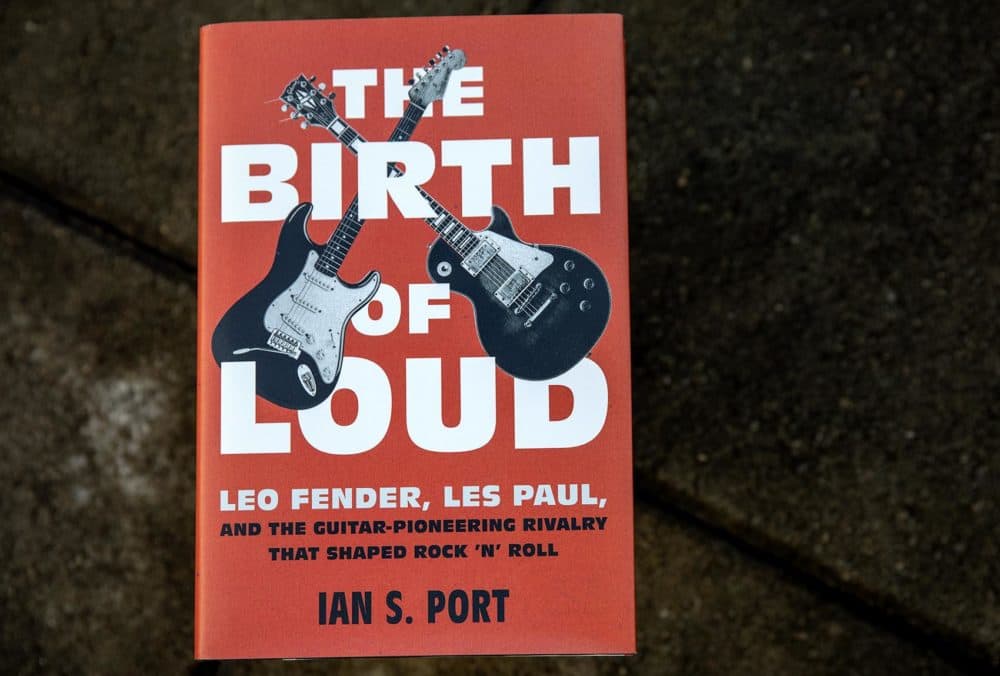

'The Birth Of Loud' Spotlights Rivalry That Gave Us The Electric Guitar

Leo Fender and Les Paul were pioneers of the solid-body electric guitar. Their innovations helped change the course of music — and put the guitar at the center of the rock 'n' roll revolution.

Fender was a master engineer who crafted now-legendary instruments like the Telecaster and the Stratocaster. Paul was a visionary musician and recording artist, and Gibson named its signature guitar after him.

Paul's arena was the stage, while Fender's was the workbench. But they shared a passion for tinkering that began at an early age, says journalist Ian S. Port, author of the new book "The Birth of Loud: Leo Fender, Les Paul, and the Guitar-Pioneering Rivalry That Shaped Rock 'n' Roll."

"Les would just kind of throw together whatever contraptions he could find, and one night when he was a kid, he tells this famous story of how he pulled the phonograph needle out of his father's phonograph set, jammed it into the top of an acoustic guitar he had and plugged that into another radio so that he could amplify his very primitive electric guitar," Port tells Here & Now's Eric Westervelt (@Ericnpr). "This was way back before 1930, before there were really even too many electric guitars on the market."

The relationship between Paul and Fender that developed in the 1950s gradually gave way to a rivalry, as Fender's guitar-making company grew and differences developed in each man's vision for the instrument.

Port's book effectively ends with Jimi Hendrix's famous performance at Woodstock in 1969. In the years since, the electric guitar has seen its share of turmoil: Gibson filed for bankruptcy in 2018, and some have even lamented the "death" of the instrument. But Port says Fender and Paul's creations continue to hold an important place in music.

"I'm struck by, watching the Grammys recently, how many performances ... featured a cameo from the electric guitar — whether that was a young R&B singer like H.E.R., or Brandi Carlile having a guitar solo in her show," Port says.

"People still want to hear it, it still has something to contribute to our music today."

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "The Birth of Loud"

Interview Highlights

On Fender and Paul's reputations as tinkerers

"Leo Fender became fascinated with radio from an early age — actually he was fascinated with pretty much everything mechanical, from the automobile to the radio. [He] started repairing his classmates' radios, and that was really how he got into the guitar world. Because as it turns out, the electric guitar's amplifier is basically an overgrown, somewhat simplified radio. Les pretty much tinkered with anything he could find, whether it was light switches or phonographs or radios, trying to find the sound he thought would set him apart as a musician — an electric guitar sound, a pure electric sound, that would define him."

On the post-World War II music scene that Paul and Fender were part of in California, and their competition to build the best electric guitar

"At the end of World War II in Hollywood, it was a real musical hotbed. There were country musicians, there were jazz musicians, of course the film industry was there, and everyone kind of knew that music was getting louder and that they needed ... more powerful instruments to ring out over the crowds that were coming to shows, and just to kind of define the new era of music.

"Les wanted a new sound because, again, he thought it would make him famous. He wanted that kind of defining thing. So he would listen to the suggestions of tinkerers who came to his Hollywood studio — he had a recording studio in his garage in his backyard in Hollywood, that kind of drew all a real motley mix of people: musicians of course, but also tinkerers like Leo Fender. Les would listen to their ideas, Leo would show up to listen to their ideas, listen to their feedback, say, 'Hey, what do you think this amplifier? What do you think of this guitar? What's the right speaker size? How should we EQ these things?' That kind of thing.

Advertisement

"Eventually that grew into a rivalry, because Leo had a company building these electric instruments. When he built finally the first commercial, solid-body electric guitar, he showed it to Les Paul, and as it turned out, Les wanted to go in a different direction."

On how the electric guitars played on tour in England in the '50s by musicians like Buddy Holly influenced the generation that would define rock 'n' roll

"The England of 1957, 1958, is really a very different place from America, and as a kid growing up in England — especially in a kind of working-class town like Eric Clapton did, or like John [Lennon] and Paul [McCartney] did — to see someone like Buddy Holly there, with kind of his full, sort of nerdy spectacles and this incredible, futuristic Fender Stratocaster that's hanging over his shoulders — imagine seeing that sort of crackling over your tiny little black-and-white television as you think about how much candy you can possibly nab from the corner store. It was quite an experience."

On Fender and Paul disliking distortion, feedback and high volume — elements at the core of rock 'n' roll music their instruments helped create

"These guys came from a radically different era in American music. They came out of the country tradition, the jazz tradition, in which musicianship and decorum were prized. And for them, to see ... popular music overrun by these wild, long-haired kids playing their electric guitars and banging out three chords as loud as they could, it was crazy. It was just completely anathema to them, and they had a hard time getting their heads around it. ... Everyone thought it would be a passing fad, more or less — especially in the '50s. The grown-ups in the music industry didn't want rock 'n' roll, thought it would go away and they were really shocked when it resurged in the early '60s, mid '60s."

Book Excerpt: 'The Birth Of Loud'

by Ian S. Port

SANTA MONICA, 1964

The screams came in waves, hysterical and elated, punctuated by applause. Then the camera found them: five men in matching striped shirts, teetering with nerves, grinning like children. The Beach Boys. A clap on the snare drum sent the song rumbling to life, and the players at the stage’s front tapped their feet to stay in time. Punches from the drum kit underpinned a sheen of male voices in harmony. But fighting for prominence was another noise—a throaty, splattering sonic current.

Curious instruments hung over the striped shoulders of the men in front. Two of the instruments were painted white, with thin bodies and voluptuous curves that suggested spaceships, or amoebae, or the human torso. Behind their players sat cream-colored cabinets the size of refrigerators, massive speakers barely visible inside, components in a new system of noisemaking. These sleek guitars transformed single notes and chords into flows of electrons, while the amplifiers converted those electrons into wild new tones—tones that came out piercingly human despite their electric hue.

There was no piano, no saxophone or trumpet, no bandleader, no orchestra. Besides their drums and voices, the Beach Boys wielded just these bloblike guitars, each dependent on electricity, each able to produce ear-piercing quantities of sound, and nearly all bearing the name Fender. Their amplified blare seemed to encourage the shrieks of fans buffeting the stage, their bodies swaying to the thrumming joys of “Surfin’ USA.”

When this scene played in American movie theaters just after Christmas 1964, it was a vision of the future. It was part of a filmed rock ’n’ roll concert—the very first—that also showed the Rolling Stones seething and strutting, and James Brown pulling off terpsichorean heroics unlike anything most of the American public had yet seen. The Teenage Awards Music International Show looked like one more entry in a procession of frivolous teen movies, but it arrived with the shock of the new. It was a multiracial assemblage of the day’s most famous pop stars, captured on film alongside bikini-clad go-go dancers and howling youths. Movie critics mostly sniffed. “Adults, unaware of the differences between these numerous young groups, view the combined efforts as fairly monotonous,” went a typical assessment. But a new order was establishing itself.

One of its precepts was racial equality, or at least the sincere pursuit of such. It was a celebration that both targeted and was beholden to the American teenager. And it prized music played on electric instruments that gave individual musicians a vast new sonic palette—and volume level—with which to express themselves.

Only fifteen years earlier, this scene would have been unrecognizable. Popular music had been the domain of dedicated artisans, trained pros in tuxedos who read notes on paper and sat on bandstands in disciplined regiments, led by a big name in a bow tie. Crooners like Bing Crosby acted out songs written for them by others, and sang for adults, not young people. Nearly everyone who joined them on the pop charts had white skin.

But in the boom years after World War II, teenagers had wrested control of the market for pop music, and many lacked their parents’ racial prejudice. Singers like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, and later Marvin Gaye and the Supremes, rose onto charts once ruled by whites. These cultural changes were accelerated by a complementary revolution in the technology of music-making. By the night The T.A.M.I. Show was filmed in 1964, anyone with the right equipment could achieve volumes that would reach hundreds or thousands of onlookers. The new rulers of music could manipulate electric guitars and amps to produce a universe of evocative or alien new sounds.

One company had done more than any other to usher in the technology that was changing listeners’ aural experiences. One company had made electric guitars into ubiquitous leisure accessories, by supplying cheap, sturdy instruments to amateurs and professionals alike. This firm was the first in its industry to align itself with the tastes of young people, among the first to paint guitars bright red and later metal-flake blue and purple, first to give its models sexy monikers like the Stratocaster and

the Jaguar.

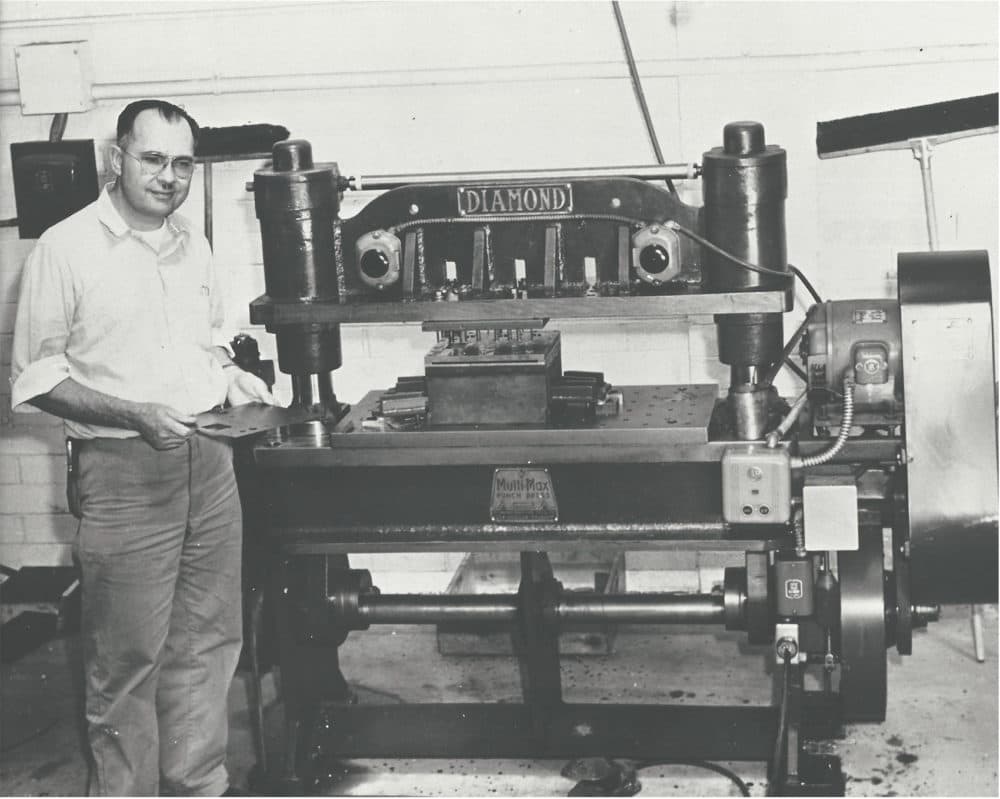

Competitors had long mocked the creations of the Fender Electric Instrument Company, but this Southern California upstart had an asset unlike any other—a self-taught tinkerer whose modesty was utterly at odds with the brash characters who used his tools. Clad in perpetually drab workmen’s clothes, preferring to spend most of his waking hours designing and building in his lab, Clarence Leo Fender toiled endlessly to perfect the tools that ushered in pop music’s electric revolution, yet he couldn’t play a single instrument himself. Instead, he trusted musicians, whom he loved, to tell him what they wanted. In the waning days of World War II, Leo Fender had started building guitars and amplifiers in the back of his radio repair shop. By that night in 1964, the company he’d built dominated the burgeoning market for electric instruments.

At least, for the moment.

Showing off their striped, short-sleeve shirts, the Beach Boys appeared clean-cut and respectable, apparently (if not actually) innocent young men. To close out The T.A.M.I. Show, a quintet of Brits arrived wearing modish dark suits and expressions of bemused insouciance, even outright hostility. The lead singer’s dark hair fell in curls down to his collar as he prowled the stage, thick lips pressed up against the microphone, hunting and taunting his young quarry. To his left, a craggy-faced guitarist beat on an unfamiliar instrument. That small, solid-bodied guitar responded with snarls and growls, a thick, surging sound that couldn’t have been more different from the thin rays of light that had emanated from the Beach Boys’ Fenders.

The earlier act embodied rock ’n’ roll life as a teen idyll, a carefree jaunt in which sex was mentioned only euphemistically, and hardly ever as a source of conflict. Minutes later, the Rolling Stones made rock into a carnal fantasy, a dim mélange of ego and lust, betrayal and satisfaction. Already labeled rock ’n’ roll’s bad boys, the five young Brits embraced the role in performance and offstage, viewing the Beach Boys—another band of white men using electric guitars to play music first created by black men—as entrants in a completely different competition.

The Rolling Stones did sound new and distinct. And part of what then fueled the difference was an instrument discovered in a secondhand music shop in London, a secret weapon for producing the nasty tones this outfit preferred. It was a guitar, made by the venerable Gibson company, that bore the name Les Paul. Thanks to Keith Richards and certain other British rockers, this Les Paul guitar would soon rise again to become Fender instruments’ prime companion and rival—just as the man it was named after had been many years earlier.

For Les Paul himself was as emphatic and as colorful as human beings come, as loud and public as Leo Fender was quiet and private: a brilliant player and a gifted technician, a charmer and a comedian, a raconteur and a tireless worker who hungered for the top of the pop charts. Out of his roots in country and jazz, Les Paul had invented a flashy style of playing that was immediately recognizable as his own, a style that would help define the instrument for generations of ambitious guitarists. But almost since the moment he began playing, Les Paul had found existing guitars inadequate. He knew what he wanted and what he thought would make him a star: a loud, sustaining, purely electric guitar sound. Nothing would give it to him.

His search for this pure tone—and through it, fame—led him to California, to a wary friendship with the self-taught tinkerer Leo Fender, who was interested in the same problem. The two men began experimenting together, pioneering the future of music. But when Les finally managed to drag the guitar out from its supporting role and deposit it at the center of American culture—and when a radical new electric guitar design finally became reality—their friendship fractured into rivalry. The greatest competitor to Leo Fender’s instruments was soon a Gibson model with Les Paul’s signature emblazoned in gold. From then on, it was Fender vs. Gibson, Leo Fender vs. Les Paul, their namesake electric guitars battling for the affections of a vast generation of players inspired by the new sound of rock ’n’ roll.

For a brief period this competition seemed to abate. But soon after Keith Richards appeared in The T.A.M.I. Show using his Gibson Les Paul, his peers in the British rock scene would find that this instrument could produce tones then out of reach of any other guitar—including a Fender. The Gibson Les Paul could become molten, searing, heavy: sounds for which it was never intended, but which were now wildly desirable. This guitar’s look and sound would go on to virtually define a new style of blues-based hard rock.

So almost from the moment the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones shared a stage in The T.A.M.I. Show, the old Fender-Gibson rivalry, that competition between the unassuming Leo Fender and the attention-seeking Les Paul, reignited. Once begun, this showdown—between bright and dark, thin and thick, light and heavy, West and East, new and old—would consume countless future musicians, as it still does to this day.

But both men’s instruments would also further a larger struggle. Whether in the hands of Chuck Berry or Buddy Holly, Jimi Hendrix or the Velvet Underground, Sly and the Family Stone or Led Zeppelin, Prince or the Runaways, Bad Brains or Sleater-Kinney, electric guitars would be used to make music with a tolerance—stated, if imperfectly applied—for people of different racial and ethnic identities. The music fueled by these instruments sought a single audience, or at least one ever-expanding group of listeners, who thought of themselves, however improbably, as young. And perhaps this bias toward diversity and youth explains some of the hostile words so casually published in 1964.

For there were proper adults in the audience of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on the night The T.A.M.I. Show was filmed. There were grown-ups sitting in the many movie theaters where it played. Were they really so bored by James Brown and the Rolling Stones, Marvin Gaye and the Beach Boys? Or did they perhaps sense that young people, armed with Leo Fender’s and Les Paul’s powerful new tools, might finally finish the cultural revolution they’d long been threatening?

Excerpted from The Birth of Loud: Leo Fender, Les Paul, and the Guitar-Pioneering Rivalry That Shaped Rock 'n' Roll by Ian S. Port. Copyright © 2019 by Ian S. Port. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Alex Ashlock produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Jack Mitchell adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on February 25, 2019.