Advertisement

Former Columbine Principal Remembers And Reflects On Resilience In The Face Of Tragedy

The audio atop this post is part 2 of a two-part conversation. Here is part 1:

Frank DeAngelis knows the pain and subsequent trauma of losing a loved one to a mass shooting.

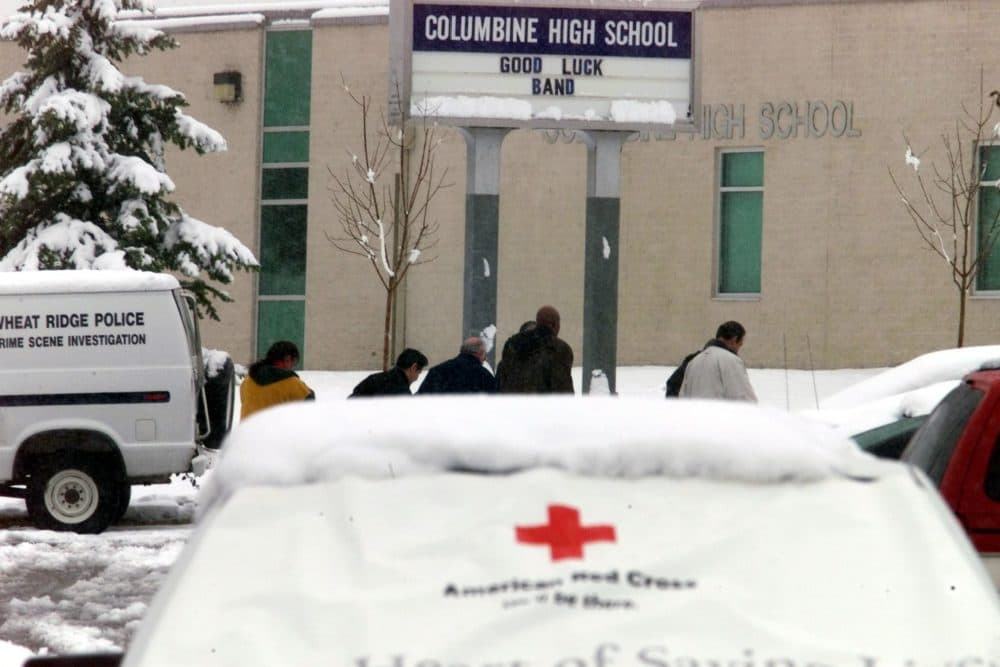

He was the principal of Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, when two teenage shooters opened fire, killing 12 of his students and one teacher and wounding more than 20 others.

"Every morning, I wake up [and] the first thing when I get out of bed is I recite my beloved 13," he says.

"Cassie Bernall. Steven Curnow. Corey DePooter. Kelly Fleming. Matt Kechter. Daniel Mauser. Danny Rohrbough. Rachel Scott. Isaiah Shoels. John Tomlin. Lauren Townsend. Kyle Velasquez. And Dave Sanders."

"I made a promise that I'm never going to let those 13 die in vain," DeAngelis (@FrankDiane72) tells Here & Now's Robin Young.

At the time, the Columbine school shooting was the deadliest in U.S. history, and the first to play out largely on live TV. Responders were prevented from going into the school until a SWAT team came — that took almost an hour — then hours more for the all-clear signal.

DeAngelis, police officers, parents and community members watched helplessly as school fire alarms wailed and at least one shot student, 17-year-old Patrick Ireland, jumped out of a window.

Advertisement

DeAngelis stayed in the school system for another 15 years, to fulfill a pledge: see every kid in the system in 1999 graduate. But when classes started back up two weeks after the shooting, he remembers his "first dose of post-traumatic stress disorder" came when parents put up balloons in an archway at the school.

"We didn't think anything of it until the balloons started popping and all of a sudden you see these kids diving on the ground, and that's when I said, ‘Oh, my gosh. It's going to be a tough road ahead.’ ”

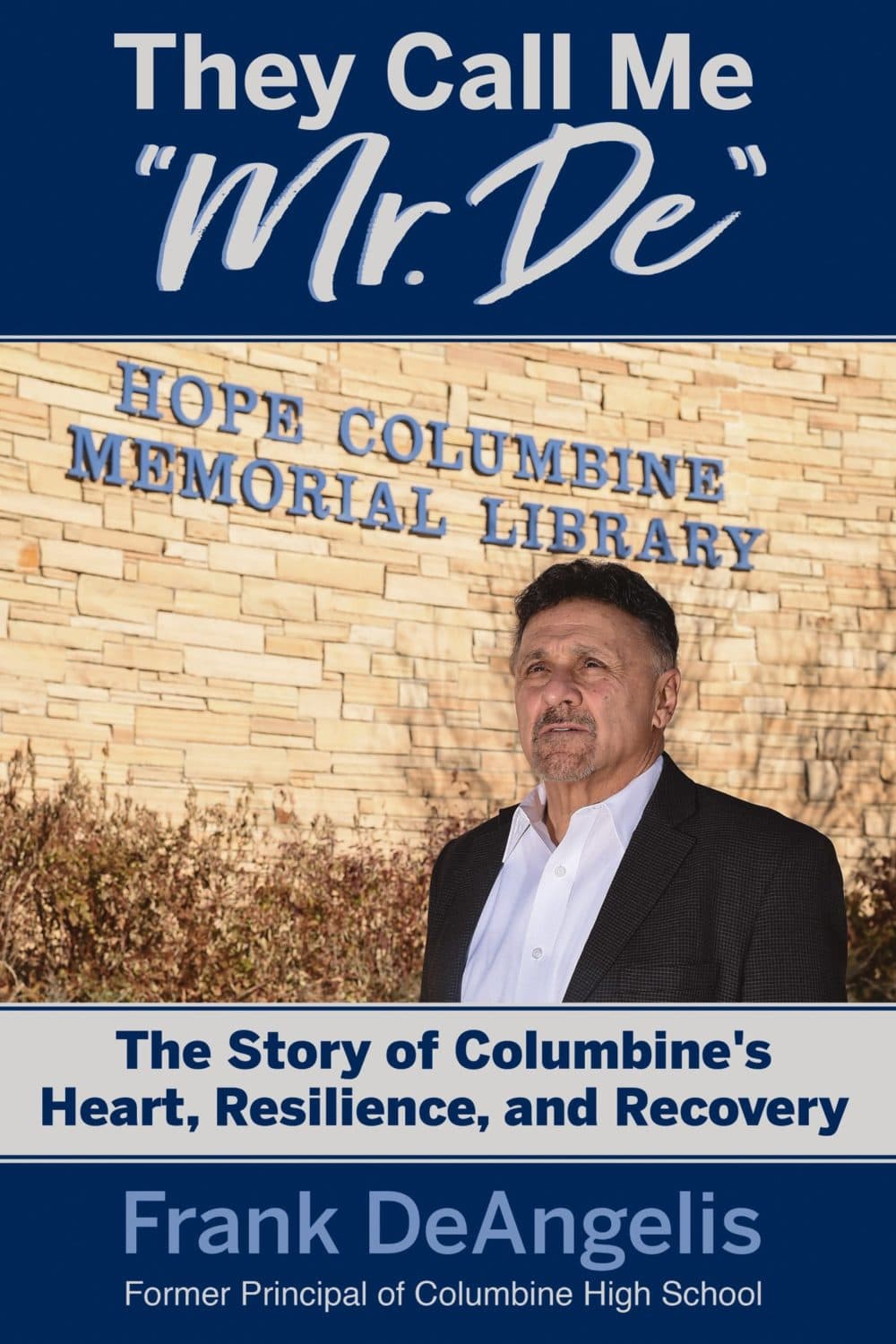

In his new memoir, "They Call Me 'Mr. De:' The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience, and Recovery,” DeAngelis openly writes about therapy, mental health and his dedication to helping those in the community heal from the trauma — including himself.

DeAngelis says he realizes how far-reaching the trauma of a mass shooting can be, even two decades later.

“One of the things that we really noticed after Columbine with so many of our students is they didn't want to share their experiences,” DeAngelis says. “And even now — I'll always call them my kids — but now they're 38 years old. And some of those parents came and said, ‘Frank, we wish we would have listened to you in being a little more persistent in getting our kids into mental health checks because they told us, we're fine, we don't need to talk anyone and now 20 years later, some of them are struggling.’ ”

Interview Highlights

On what happened when he first heard gunshots on April 20, 1999

“The first thing that crossed my mind is this has to be a senior prank. This cannot be happening. And my worst nightmare became a reality because I encountered the gunman. Everything just kind of slowed down, [I was] not sure what I was going to do. What was it going to feel like to have bullets pierce my body? Now, through counseling [and] through some type of techniques, I learned why I continued to go towards that gunman because I had about 25 girls that were coming out of the locker room to go to a physical education class.”

On finding the correct key among 35 keys to open a door — ultimately saving 20 students and himself

“And that key story, because it was a key of 35, it was in the middle of these keys — if I wasn't able to find that key on the first try, who knows? I probably would not be doing this interview. But the thing that adds to the survivor's guilt is I found out later through police reports that Dave Sanders, again, he was my mentor. If he would have stayed in the faculty lounge, I would have died that day, because what happened is he ran up the staircase and as he's running down to warn kids, the gunman was coming toward me and he catches a glimpse of Dave so he stops momentarily to turn around and unfortunately he shoots Dave through the back of the head. And that moment that caused the gunman to slow down as he was coming toward me and the girls probably saved our lives.”

On the emotional reaction of retelling his experience

“When I tell the key story I get chills and I think of those girls screaming. I hear the gunshots. I remember that door — pulling on it. But then, what I have to do and I learned this through my counselor, is I have to replay things differently. I have to think back to Dave Sanders and the time we spent together teaching and coaching. One of the things that has really helped me get through this is, these girls. They send me pictures now of their daughters or sons and they said, ‘Mr. De, I am so grateful you found that key. If not, I wouldn't have this beautiful family.’ ”

On what’s been improved upon since the mass shooting at Columbine High School

“There's a couple things that really have improved greatly. We have proven that locked classroom doors are a key to protecting students and staff. These perpetrators realize that the event is going to be over within 10 minutes because of the change in protocol. There's going to be responding officers. So if they come into a classroom and that door is locked, they're going to move on to what they consider a soft target.”

On his thoughts on tougher gun regulations

“That's the question I get asked especially last year after Parkland, politicians coming out and saying, ‘If we have tougher gun laws, there is never going to be another school shooting.’ And that's where I disagree. I mean, [there are] loopholes.

“But what I question is when people say that [the lack of gun control is the] only thing that's allowing this to happen, because I think back to Columbine, the two gunmen ... purchased some guns illegally that were used in the killing.

“We also have to look at students that may be struggling. It saddens me when school districts are cutting back on mental health and then the role that social media is playing in these kids lives. And then you add the parenting, so now you take each piece of this puzzle, you put it together and we have a chance of stopping these massacres from occurring.”

On coping with the trauma two decades later

“I'm pretty emotional. I make the joke that I get emotional at the grand opening of a Walmart. I mean, I cry when I present. It comes back. I share a story about Sean Graves, when Sean Graves was paralyzed. And I would go visit those kids, Sean Graves, and Patrick Ireland, and Anne-Marie Hochhalter and Richard Castaldo — they gave me hope. There was a chance Sean would never walk again. I said, ‘Sean, I'm looking forward to when you graduate and me handing you your diploma.’ He worked hard. He passed all of his classes, but he did not walk until that day. About 10,000 people [were] there and they announced his name, and all of a sudden Sean puts his hand up, gets out of the wheelchair, and walks over to get his diploma and he said, ‘Mr. De, I'm here to get my diploma. Thanks for never giving up on me.’

“Patrick Ireland, the boy in the window … he could not even put three words together to make a sentence. Less than nine months later, he graduated No. 1 in his class, valedictorian in the class of 2002. He went on to [Colorado State University], graduated [in the] top 10 percent. The kid is just phenomenal. I can remember he invited me to his wedding. And I'm sitting in the church [and] Kenny Kozak, who is a director at Craig Hospital, tapped me on the shoulder [and] I turned around. He's crying, I'm crying and he said, ‘Did you ever think that you would see Patrick Ireland walking down the aisle to marry that beautiful woman?’ Patrick has two daughters and a son. He's my financial adviser and I am so happy Patrick’s alive.”

On his advice to other principals who have witnessed mass shootings in their own schools

“When I have those conversations with Ty Thompson, the principal from Parkland, and Rachel Blundell from Santa Fe, I said, ‘Don't ever give up hope because where we were 19 years ago and ... where we are right now, there is hope. So don't ever give up.’ And I said, ‘I'm not going away. I'm going to be with you every step of the way.’ ”

On hearing about the suicides that happened after mass shootings in Columbine, Parkland and Sandy Hook

“It was difficult when I heard about the two students, it took me back. I remember exactly six months and two days after our tragedy, one of our students who was critically injured, Anne-Marie Hochhalter, [her] mom took her own life. It was the following May, one of our students — who was in the classroom with Dave Sanders — took his own life, Greg Barnes. And then when I heard about Jeremey [Richman], it really hit hard, because the summer after Sandy Hook, he came out to Colorado, just a wonderful man and he was talking about healing, and he was talking about all the work he was doing with brain research. And so, when it came across the wire that he had taken his own life, it hit pretty hard.”

On dealing with the trauma after a mass shooting

“Some parents came up to me and said, ‘Frank, even though we didn't lose our students, even though they did not die, we have lost our students.’ You hear stories like Amy [Over]. There was a young lady, Michelle Romero Wheeler, [who] came into my office in 2012 … just crying uncontrollably and I said, ‘What is going on, Michelle?’ She said, ‘Today, my little girl is getting ready to walk her up to the door at kindergarten and she held her hand and then all of a sudden [the] little girl starts walking and [Michelle] runs up there and grabs her and clenches her chest. And everyone's coming up saying, ‘You alright? You alright?’ And she said, ‘I was struggling and my little girl saying, “Mommy, mommy, you're hurting me.” And all I could think about [was] if I allowed her to walk in that building, there is a chance she may not come home.’ ”

On how certain things can be really tough to deal with

“If a balloon pops, I mean, I'll start crying. I was helping one night at parent teacher conferences and all of a sudden the car backfired. Luckily the police officer was a friend of mine. He knew exactly what I was going through because I bent over and started shaking. Yesterday I had a chance to talk to Craig Scott and his mother, Beth. We were together and he was just sharing these stories. And for me, for example, last year when the Parkland shooting happened on February 14, I was getting off a plane and I turned my phone back on. And when I start getting a text saying, ‘You're in my thoughts and prayers. If you need anything let me know.’ Well within five minutes, I can guarantee my phone is going to start ringing. So you are retraumatized.”

On going to therapy

“There is a stigmatism and people still feel that if you seek mental health or counseling, that's a sign of weakness. And there were some people that advised me if you do [seek therapy], you better not tell anyone because they may see you're deemed unfit for duty. A good friend of mine, my mom actually worked for him, John Fisher and he was a Vietnam veteran. He said, ‘Frank, you're going to be pulled in so many different directions and everyone needs you. But if you don't help yourself, you can't help anyone else.’ And that's a message I share when I go to Parkland and Santa Fe and Sandy Hook. But another key component [is], I'm a cradle Catholic and right after the event, I was questioning my faith. It was a couple of days later Father Ken Leone, who was the pastor over at St. Frances Cabrini where I had been a member for 20 years, he said, ‘Frank, you need to come down to the church.’ I said, ‘Father, I just can't. I'm not in a good place.’ He said, ‘You need to come down.’ And when I walked into the church there was over 1,200 people and many were students because they were part of the youth group and he called me up on the altar and we prayed. But the thing that he whispered in my ear was, ‘Frank, you should have died. But God's got a plan for you.’ ”

On the false narratives that arose about the shooters after the mass shooting

“It was so frustrating because I promised to protect our kids from some of the information that was being passed out. But there were also pending lawsuits. So many times, I couldn't say and those initial reports, unfortunately, are still the first narrative are still being believed 20 years later.”

On what could have been done differently

“One of the things I need to say is the police, they got unjustly criticized. I was on the street and I was the one drawing blueprints and I was the one that they were going to put a bulletproof vest on to go disarm the fire alarm. But many of those police officers, they were angry, because they were being told that they had to stay outside and it was a protocol. And as a matter of fact, we had a school resource officer outside exchanging gunfire. That's one of the most frustrating things for the people who were trapped in the building because they were looking outside at the window. There must have been 500 responding officers, but no one was coming into the building until the SWAT team [arrived].”

Book Excerpt: 'They Call Me Mr. De:' The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience, and Recovery'

by Frank DeAngelis

I was the principal at Colorado's Columbine High School on April 20, 1999.

I remained principal for fifteen more years.

Virtually every day at the school, I heard variations of How can you do this? How can you go back? How can you walk those same halls? How can you be reminded every day?

Many friends and colleagues urged me to move on. I refused to seek or accept a transfer to another school in Jefferson County or move to the Jeffco Public Schools central administration. I needed to be at Columbine. I wanted to be there; I couldn’t walk away. Not from the kids, not from the high school, and not from the suburban school community to the southwest of downtown Denver. I wanted to see to it that Columbine came to define something other than tragedy. I wanted it to become a story of courage, love, heart, resilience, and recovery. I wanted to lead the way to that healing.

In the spring of 2014, I looked out from the stage at Fiddler’s Green Amphitheatre in Greenwood Village at the more than four hundred Columbine seniors. They would be my last class. I had been at the school for thirty-five years. Before becoming principal in 1996 and spending eighteen school years in that job, I had served seventeen years in a number of roles, including a social studies teacher, dean of students, assistant principal, and coach.

These kids knew me, and always would know me, as “Mr. De.”

Well, that or “Coach De” or “Papa De.”

They were my kids.

That day, after taking a selfie with my final graduating class behind me (proving that you can teach a veteran educator new tricks), emotion choked my voice as I spoke to those seniors:

“My first class was the class of ’97, and my last is this class,” I said. “We are family. We are Columbine. Once a Rebel, always a Rebel. You’ve made me a proud papa. I love you.”

Teacher and coach Ivory Moore then went through an emotion-filled school tradition, leading us in our school chant: “We Are . . . Columbine.” It built to a crescendo and illustrated that sometimes simple is the most effective approach.

Looking out on those fresh faces, students filled with dreams of what might be for them, I thought back to the promise I made at vigil held on April 21, 1999, at Light of the World Catholic Church. That tearful morning, with school district officials and politicians listening, I vowed to the students I would remain principal until the classes enrolled at Columbine at the time of the tragedy had graduated.

That would have taken me through the Class of 2002.

Soon, though, I extended that to cover the kids attending classes in the Columbine feeder system in April 1999 as well. That committed me through the Class of 2012.

I reached 2012 on the job . . . and kept going.

I stayed on, at least in part, because a parent informed me her child was in the first year of a two-year preschool program in April 1999 and wouldn’t graduate until 2013. Those kids, as young as they were in 1999, were mine, too. So I stayed through the 2013 commencement and went one more year. Suddenly, or so it seemed, spring of 2014 arrived. I knew it would be my final graduation ceremony as principal of Columbine High School. I was finishing up.

Most of those kids in front of me at Fiddler’s Green, the Class of 2014, had been three years old on April 20, 1999. They knew my history, knew my commitment, and knew I loved them and that I wasn’t hesitant about showing it.

As a school and as a community, we had been through so much. Outsiders wanted to fixate on the horrors or on the killers, but we remembered the dead and wounded. We honored them by turning “Columbine” into a story of heart, love, resilience, courage, and recovery. Every day I reminded myself, our students, staff members, and anyone else who would listen that “We were a great school, we are a great school, and we will continue to be a great school. The members of the Columbine community make it great.” At the one-year anniversary of the tragedy, we coined the phrase, “A Time to Remember, a Time to Hope.” Those words, along with “Never Forget,” are still appropriate and often cited.

The students crossed the stage to receive their diplomas from the dignitaries and then found me waiting at the bottom of the steps to congratulate them. The hugs were plentiful, and I knew we had succeeded in transforming the story. Together we made it through the heartache, anger, and despair.

That is the true and important Columbine story nearly twenty years after the murders.

Since retiring in 2014, I’ve been telling the story to audiences across the United States, Canada, and Europe. I’ve spoken to leaders in business and education, to mental health groups, to judges, prosecutors, and justices, to district attorneys, to firefighters, police officers, and other first responders, and to students at school assemblies and leadership academies. Thousands have heard me speak about the Columbine story, and thousands more will hear it in the foreseeable future.

At my presentations, I usually am asked if I am writing a book or told I should write one.

Finally, here it is. It’s time.

In the days and years after the killings, I had to be guarded in my responses and public comments about the two murderers and the events of the day. I couldn’t aggressively respond to the media’s misstatements and exaggerations or the internet-driven myths. Lawsuits were pending against the school district and Jefferson County, and I was named in eight of them. I was ordered not to address issues tied to the litigation. Even if that hadn’t been the case, I wanted to keep the focus on the recovery while respecting the memories and the families of murdered students: Cassie Bernall, Steven Curnow, Corey DePooter, Kelly Fleming, Matthew Kechter, Daniel Mauser, Daniel Rohrbough, Rachel Scott, Isaiah Shoels, John Tomlin, Lauren Townsend, and Kyle Velasquez.

I wanted to honor my dear friend, teacher-coach Dave Sanders, who was murdered that day.

I wanted to support the twenty-six others who were physically injured or wounded—and the countless others in our school and community whose hearts were forever scarred by what we’d witnessed.

On the personal level, the horrific events of April 20, 1999 don’t define me as much as does the strength of the Columbine student body, staff members, and community. I’m confident that my love for young people and my job resonates with those who have made public education their careers. I needed Columbine—its people, its heart—more than it needed me.

During my presentations, I tell audiences of my background, how I turned to education and coaching after realizing the New York Yankees weren’t going to draft and sign me, and that my back-up plan of accounting wasn’t for me. I tell them how I handled the tragedy, not just that day, but for years beyond. People in those audiences feel a sense of empathy; a bond of sorts forms as they come to understand how we fought and transformed the story—how we did it together.

This book includes input from my siblings, Anthony DeAngelis and LuAnn DeAngelis Dwyer; my high school sweetheart and wife, Diane (there’s a story there, and we’ll get to it in a bit); my life-long best friend, Rick DeBell; my high school teacher, baseball coach and mentor Chris Dittman; and, finally, my Columbine compatriots, Tom Tonelli and Kiki Leyba, both terrific teachers who, as of this writing, still are on the school faculty. Tom is a 1988 Columbine graduate who joined the faculty in 1994. Kiki dropped out of high school at age sixteen and earned his GED while working in construction. He attended Metropolitan State in Denver, did his student teaching at Columbine, then began his teaching career with us in 1998–99. My motivation in including their voices is to add to the portrait and narrative of our story and not to be showered with praise, with Kiki and Tom as representative voices of the Columbine constituency. Ricky, by the way, good-naturedly held out for a payment of $3.82, seeking to match the combined prices of a cannoli, Tuddy Toots, Little Devil, and a Coke at Carbone’s in the North Denver of our youth!

Excerpted from They Call Me 'Mr. De:' The Story of Columbine's Heart, Resilience, and Recovery. Copyright © 2019 by Frank DeAngelis. Published by Dave Burgess Consulting, Inc. All rights reserved.

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This article was originally published on April 02, 2019.

This segment aired on April 2, 2019.