Advertisement

From Massive Boxcar To Tiny Shoe, Artifact-Rich Auschwitz Exhibit Tells The Holocaust Story

There is a stunning sight outside New York's Museum of Jewish Heritage: a huge brown cattle car, the kind the Nazis used to transport Jews and others to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

It's part of an exhibit, titled "Auschwitz. Not Long Ago. Not Far Away," which includes more than 700 artifacts and 400 photographs. The exhibit, which opens Wednesday, is a partnership with the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland. It's the most comprehensive Holocaust exhibition about Auschwitz ever seen in North America.

Auschwitz expert, historian and preservationist Robert Jan van Pelt was one of the exhibit's creators. Standing in front of the boxcar, he describes the stark conditions the prisoners inside it experienced — crammed into the small space with more than 80 people, no food, no bathroom, no place to sit or lie down. But more significant was what the ride meant.

For most, that trip to Auschwitz was the last time they were surrounded by family.

"The moment the door opens, you arrive in Auschwitz," van Pelt says, "all that disappears in a flash, because everyone gets separated without opportunities to say goodbyes."

Van Pelt adds that when the exhibit first opened in Madrid prior to coming to New York, his 92-year-old father collapsed in tears.

"And I thought actually he would die," he says. "But you know, history is not safe."

Inside the museum, board chair Bruce Ratner says his desire to bring the exhibit from Spain to New York started with a visit to Madrid.

"It was difficult," he says of seeing the exhibit for the first time. "I had lost a number of members of my family [during the Holocaust.]"

Despite already working in a museum dedicated to the Holocaust, he said the impact of this one in particular hit him hard.

"It's almost difficult to describe — 700 artifacts and objects, 400 photos. It's so detailed and the artifacts are so meaningful that you can't help being impacted in a way that I've never been impacted by any exhibition before," Ratner says.

Advertisement

Visitors enter the museum through a long, dark corridor, where TV screens show snapshots and video clips of life before the war: Jewish families at the beach; a mother cooking; teenagers rough-housing on the street. On the wall, there’s a quote by Auschwitz survivor and author Primo Levi: "It happened, and therefore it can happen again."

It's a message Ratner says is at the heart of the exhibit.

The exhibit rooms are carefully curated to represent different moments in Auschwitz's history, from the history of anti-Semitism to the liberation of the camp. One of the first depicts the spread of the Aryan philosophy and its earliest victims.

Van Pelt gestures towards a white medical coat. He calls it one of the most chilling artifacts in the exhibit.

"When the war broke out, the Germans also started killing the disabled," van Pelt explains. "Dr. Georg Renno murdered more than 20,000 people because they were disabled. When we accept that we are going to kill our own people who are not capable of functioning in the racially pure society, who can stop us to kill the others?"

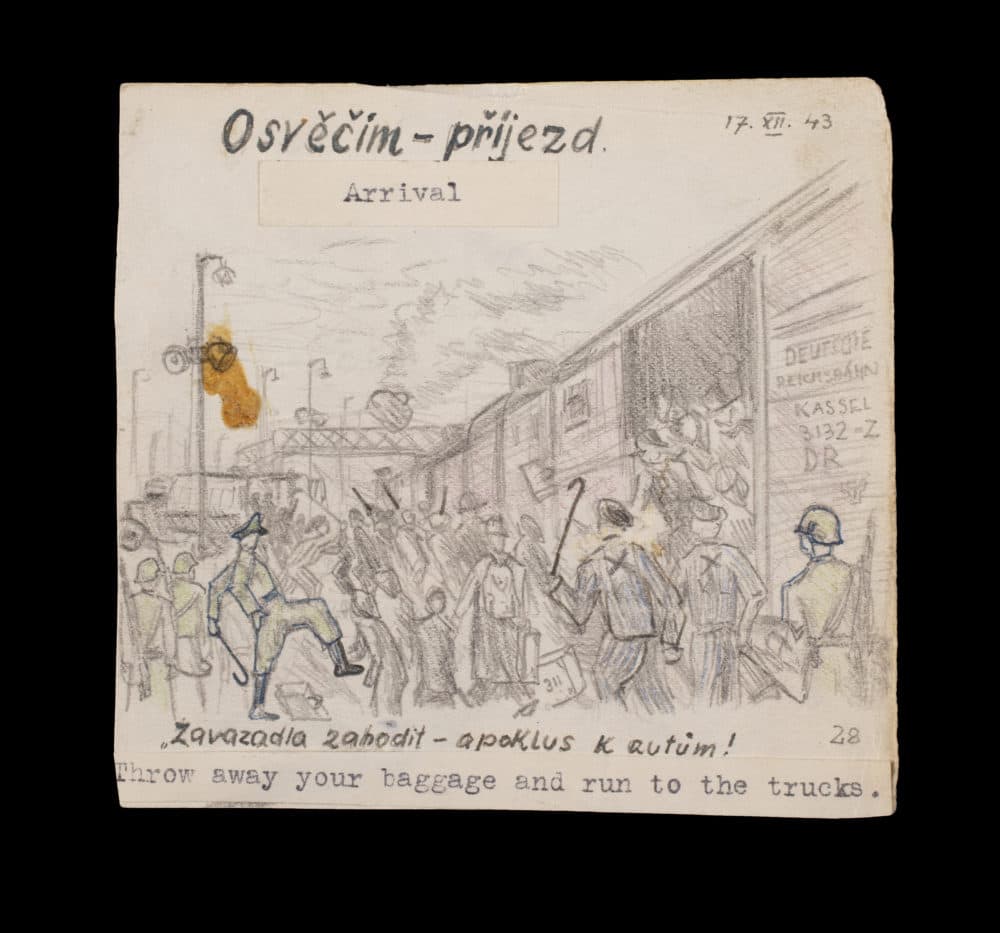

The next room is devoted to deportees. There are the postcards prisoners threw from the cattle cars, hoping that someone would mail them. There's a display of suitcases. There's also a display that van Pelt calls a memorial to the children who were murdered. It includes a handmade doll, buttons, a little onesie.

"You never get used to it," van Pelt says, choking up. "In some way the core of the Holocaust is the murder of the children."

The next room deals with some of the most painful Holocaust artifacts: those dealing directly with the gas chamber. One of them is a little boy's shoe, made of cracked brown leather. Inside the shoe is a tiny brown sock.

"We literally look at the last act of a little boy," van Pelt says. He explains that a mother or sister probably told the child to put his sock into his shoe, "like you'd do at the swimming pool."

"He's now naked to go to the showers. And he does it because he expects to come back. And he doesn't come back," van Pelt says.

Next there's the door into the gas chamber room. First, the perpetrator's side, with door handles, hardware to open and close the chamber and to lock people in. There's also a peephole.

Van Pelt walks around to the other side — the prisoners' side.

"There's no hardware anymore. There's no way that anyone crammed in there would be able to do anything … you're crammed with 2,000 people in a gas chamber. There's nothing you can do anymore," he says. "You're naked, the door closes. The gas comes in … and the only agency you have left is to try to break the peephole. As though that will make any difference."

Van Pelt says the design of those doors — the fact that an architect created them — was his impetus to study the Holocaust. He needed to find out why.

After several more rooms and artifacts that include a stretcher to carry the dead and a diorama of the camp, visitors arrive at an area dedicated to liberation. There, visitors see a gray house coat, or bathrobe. Van Pelt tells the story of Yacob Gruenbaum, a tailor whose family was murdered. After Auschwitz was liberated, Gruenbaum went to work as a tailor for the U.S. Army, which had liberated the camps. During this period he heard about an abandoned warehouse full of Nazi uniforms.

"So Yacob goes into that warehouse and takes a bale of that material, and then out of that SS material he makes himself a house robe," van Pelt says. "This man had been a slave, miraculously he survives, so one thing he didn’t have for six years was an opportunity or place to wear a house robe."

Gruenbaum then met and married a local girl.

"And the girl is my mother-in-law," van Pelt says.

For people like van Pelt, it's these kinds of personal ties that create a sense of urgency to study the Holocaust, and to educate others about the horrors of the war.

"I don't think you get into this field if it's not personal," he says. "There are many children, grandchildren of survivors. And I think we all struggle with what to do with their legacy."

At the end of the exhibit as visitors leave, they see a quotation from a survivor. Van Pelt reads it aloud.

You who are passing by. I beg you. Do something. Learn a dance step; something to justify your existence. Something that gives you the right to be dressed in your skin and your body hair. Learn to walk and to love. Because it would be too senseless, after all, for so many to have died, while you live, doing nothing with your life.

The quote reflects a message van Pelt says he hopes people take away from their visit.

"That they appreciate how precious this life is."

This segment aired on May 8, 2019.