Advertisement

Here & Now Bookshelf

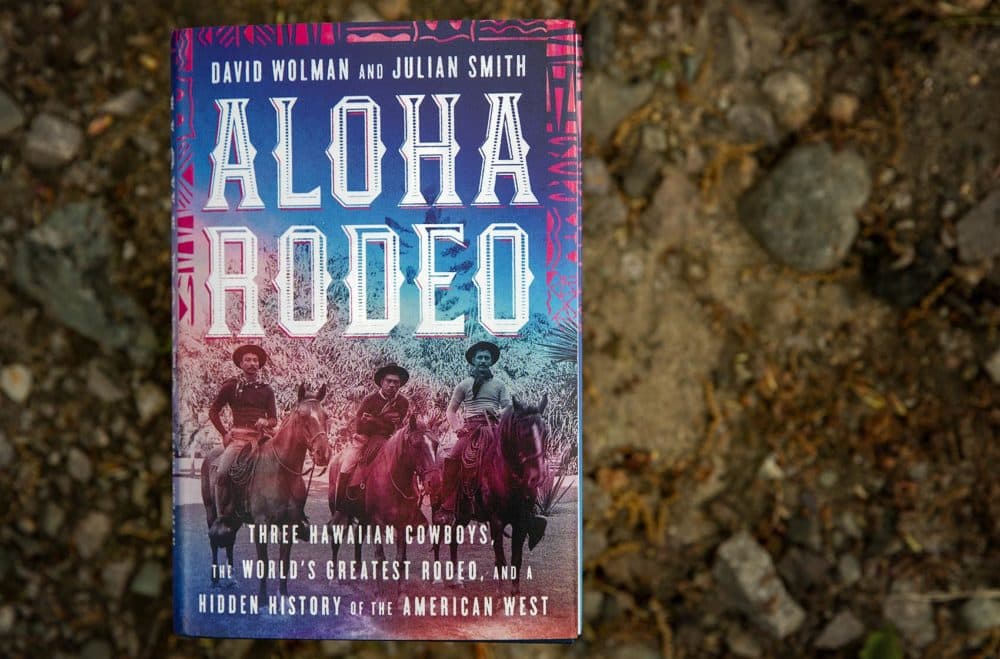

'Aloha Rodeo' Book Illuminates The History Of Hawaiian Cowboys

Editor's Note: This segment was rebroadcast on July 3, 2020. That audio is available here.

In 1908, three riders from Hawaii came to compete in the biggest rodeo in America — Frontier Days in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Their abilities stunned spectators unaware of Hawaii's cattle culture.

Here & Now's Peter O'Dowd talks to authors Julian Smith (@Julianwrites) and David Wolman (@davidwolman) about their new book, "Aloha Rodeo: Three Hawaiian Cowboys, the World's Greatest Rodeo, and a Hidden History of the American West."

Book Excerpt: 'Aloha Rodeo'

The new world’s first cowboys were called vaqueros, from the Spanish vaca, for cow, and querer, to love. Vaqueros wore clothes that combined practicality with ornamentation: hats with wide upturned brims, low-heeled boots with jingling metal spurs decorated with silver, and pants adorned with bright buttons up the seams. Their skills at riding, roping, and herding, combined with their distinctive look, gave them prestige among men and women; it was said a vaquero would dismount only to dance with a pretty girl.

By the early nineteenth century, it was clear that Hawaii’s bullock hunters couldn’t keep up with the islands’ soaring cattle populations. Through increasing trade with North America, the monarchy had learned that vaqueros managed herds of tens of thousands at sprawling ranchos in Alta California. Here, finally, was a possible solution to Hawaii’s bovine nightmare—and a potential moneymaker. In the early 1830s, Kamehameha III sent a royal decree to mission contacts in California. The king requested that vaqueros come to the islands to teach Hawaiians the basics of roping and herding. That same year, perhaps a dozen men, roughly three for each of the major islands, traveled from California to Hawaii.

Advertisement

The vaqueros brought their own well-trained mustangs, which traveled in first class compared to livestock, with regular brushing, water, and fresh food. Storms aside, the most stressful part of the journey was the end. As one historian noted, “While embarkation in California meant dockside loading, the vaquero was apprehensive about casting his mount overboard in Kawaihae Bay for the swim to shore.” But there was no alternative.

Customized gear was also critical, starting with a leather-covered saddle often stamped with intricate geometric or floral patterns. A vaquero’s most important and treasured possession, though, was his reata, the root of the English word lariat. Braided painstakingly by hand out of four strips of carefully chosen rawhide, the lasso was usually about eighty feet long. A rider’s job, and sometimes his life, depended on his proficiency with the rope. When it rained, the lariat was the first thing the vaquero protected.

Cowboys in Spanish Mexico had put their lassos to uses beyond herding cattle. During the Mexican-American War, local ranchers pressed into fighting employed them as weapons against American troops; dragging a man to death didn’t cost any bullets. According to one story from the Mexican Revolution, a soldier once roped the muzzle of a small cannon and dragged it off. Lassos also came in handy during bear hunts in California. A colorful 1855 account in Harper’s Magazine described how Mexicans, who could “throw the lasso with the precision of the rifle ball,” would corner bears and rope them around the neck and hind foot. “[A]fter tormenting the poor brute and . . . defying death in a hundred ways, the lasso is wound around a tree, the bear brought close to the trunk and either killed or kept until somewhat reconciled to imprisonment.”

In 1840, a young Yale graduate named Francis Allyn Olmsted was traveling the South Pacific and, upon arriving in Waimea, noticed men dressed in ponchos, boots with “prodigiously long spurs,” and pants split along the outside seam below the knee. Olmsted watched as the men corralled cattle and branded each one prior to shipment to Honolulu: “In an instant, the lasso was firmly entangled around his horns or legs, and he was thrown down and pinioned. The burning brand was then applied, and after sundry bellowings and other indications of disapprobation, the poor animal was released.”

The vaqueros taught the bullock hunters that the lasso was a more effective tool than the rifle. Ranching meant careful management: organizing, moving, slaughtering, breeding. It was about fences and grass, brands and paddocks. This was how to bring the wild herds of Mauna Kea under control.

The men from California also taught the Hawaiians how to work with the horses that had first arrived in the islands in 1803, when an American merchant ship had brought four mounts from California as gifts for Kamehameha I. This time the king’s reaction was more subdued. Even if riding was faster than walking, he asked shrewdly, would the animals be worth the food, water, and care they would require?

But in the end he accepted the gifts, and within a matter of decades, horses had become an integral part of daily life and tradition throughout the islands. Hawaiians quickly took to riding, and there is mention of importing more horses to the archipelago as early as the mid-1820s. Hawaii’s first horses were mustangs from the wilds of New Spain, descendants of the tough animals the conquistadors had brought to the New World in the sixteenth century. They were Arabians, probably the oldest horse breed in the world. These compact, hardy survivors could thrive in harsh landscapes—their long-distance endurance is legendary—and they had experience working with cattle that made them perfect for their new job in the islands.

Hawaiians also adopted the vaqueros’ spirit of competition. During annual roundups, or rodeos, ranches in New Spain hosted matches in which vaqueros faced off in friendly contests. These games were sometimes brutal, such as grizzly roping, or races in which riders tried to grab a live rooster buried up to its neck in the ground. Others were controlled versions of tasks the vaqueros performed every day: sprinting on horseback, lassoing and tying up steers, and breaking wild horses to the saddle.

As Hawaiians became more adept with the vaqueros’ methods and tools, they absorbed many of their mentors’ sensibilities about work, animal husbandry, and even style. Some of the men Olmsted observed, in fact, were likely native Hawaiians dressed in what was fast becoming standard garb for island cowboys.

Yet they also created a uniquely Hawaiian tool kit. They slimmed down the heavy, bulky Mexican saddle into the Hawaiian tree saddle, so called because it was carved from the wood of local trees, just as their ancestors had carved canoes out of koa. Local saddlemakers added a high saddle horn for dallying, or tying, the free end of a lasso. Hawaiian riders used smaller spurs than the long Mexican ones, so as not to trip on jagged lava rock.

Hawaiians took to cattle ranching with such enthusiasm and skill that soon the vaqueros had nearly put themselves and the bullock hunters out of a job. “Already the old race of Bullock catchers (a most useless set in other respects) is becoming extinct,” wrote a local rancher in 1848. Eleven years later, the Honolulu papers reported that the vaqueros who had come to teach the Hawaiians “how to lasso, jerk beef and cure hides” were all but gone, either back to North America—perhaps to California to chase gold rush fortunes—or else absorbed into Hawaiian society.

In their place were Hawaiian cowboys called paniolo, a local twist on the word español. The legendary cattle drives of the West were still a generation away, but here on the plains of Waimea and elsewhere in the islands, paniolo were working cattle—before there was ever such a thing as an American cowboy.

From the book ALOHA RODEO: Three Hawaiian Cowboys, the World's Greatest Rodeo, and a Hidden History of the American West by David Wolman and Julian Smith. Copyright © 2019 by David Wolman and Julian Smith. From William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Emiko Tamagawa produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on May 27, 2019.