Advertisement

Mapping Out Philadelphia's Jazz History

Jazz piano great and Philadelphia native McCoy Tyner died last week.

“McCoy Tyner represents the best of Philadelphia,” says Faye Anderson, director of public history project All That Philly Jazz. “He came out of the Philadelphia ecosystem that supported young artists.”

After he passed away, Anderson says she received an email from Maxine Gordon, the wife of tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon. Maxine Gordon said Tyner loved sharing the story of playing piano in his mother’s beauty shop, Anderson says.

The family lived above the shop — the largest room in the house, Gordon told Anderson. Tyner’s “Blues on the Corner” is a tribute to the beauty shop, which used to sit on a corner in West Philadelphia, she says.

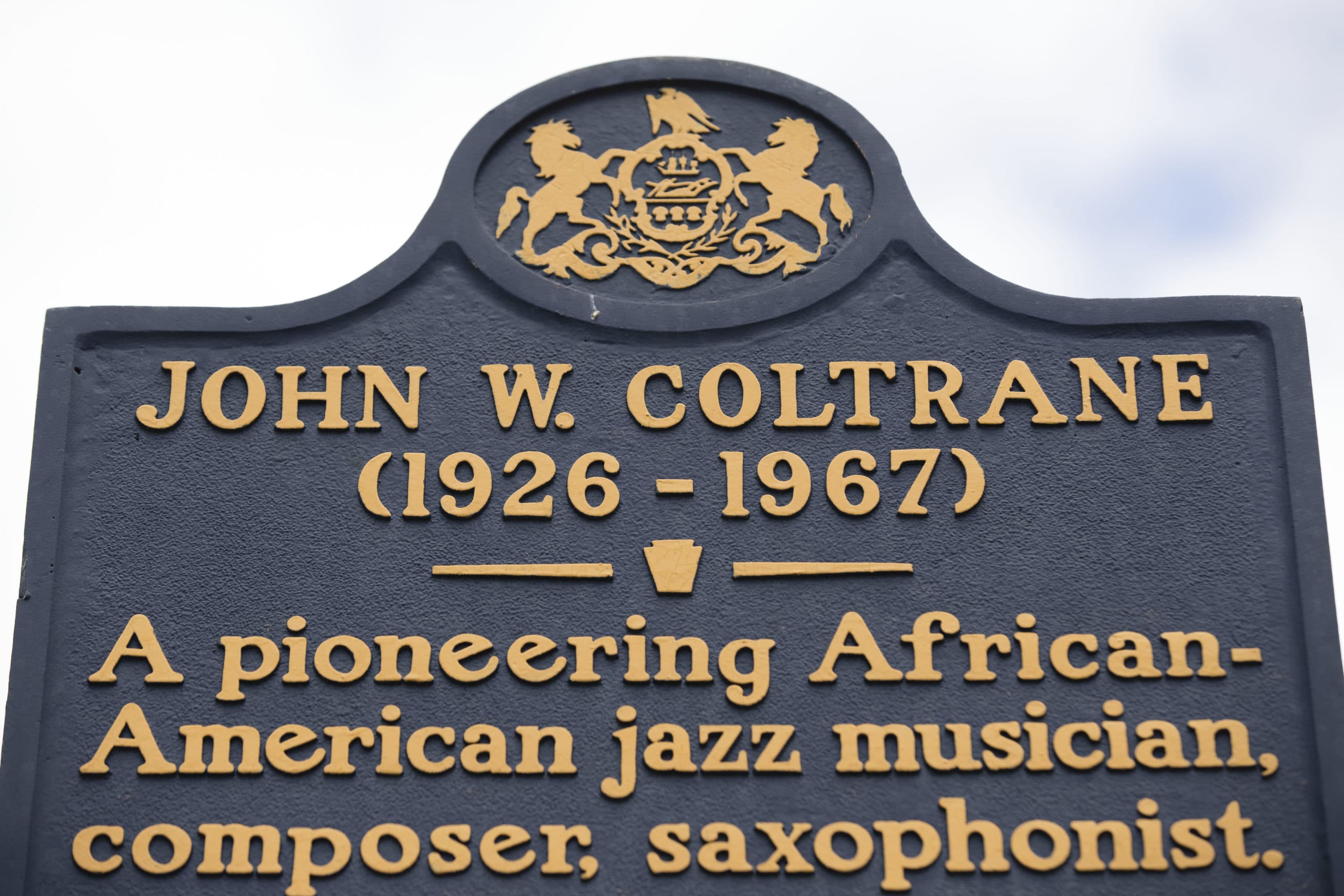

During Philadelphia's golden age of jazz, Tyner played with other jazz legends like saxophone player John Coltrane, who also grew up in the city.

“There was jazz everywhere, so there were opportunities to sit at the feet of the jazz legends of the day,” she says. “You can't overstate how much jazz was part of the Philadelphia life.”

The John Coltrane Quartet and other jazz icons would play venues like the Heritage House, which held concerts for people under the age of 21, she says. Between sets, legends like Ella Fitzgerald, Johnny Hodges and Chet Baker would come to the Heritage House to play and offer jazz workshops, she says.

The Heritage House is still standing, now called the Freedom Theatre. But some of the city’s robust jazz history — like the house where Coltrane lived and kicked his heroin habit — is in danger of disappearing.

This year, the house where Coltrane recorded “Blue Train” was placed on Preservation Pennsylvania's list of at-risk sites. The house is an “eyesore,” Anderson says.

On top of recording his first big album in the house, Coltrane also lived there when he met Tyner, she says.

Advertisement

During the day, Coltrane fought to quit heroin cold turkey in his second-floor bedroom, she says. By night, he played a gig at a West Philadelphia club called Red Rooster — where he met Tyner. The duo would practice at Coltrane’s house.

“Before McCoy Tyner's death, I would say that I am fighting to save this national historic landmark in the name of John Coltrane,” she says. “I will now say I'm saving it in the name of John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner because you cannot separate the two.”

Most of the city’s historical jazz sites are gone. That’s why Anderson believes it’s important to preserve the few still-standing buildings like the Coltrane house.

One building that’s no longer standing is Music City, a space above a record shop where saxophone great and Philadelphia native Stan Getz would play for fans. The venue was known for jam sessions for young people that featured influential musicians like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis, she says.

Composed by jazz tenor saxophonist and Philadelphia native Benny Golson, the song “I Remember Clifford” is about up and coming trumpeter Clifford Brown who played his last gig at Music City. Brown left the venue to travel to another gig in Chicago, but he was killed in a car accident along with his wife and another passenger, Anderson says.

Jazz brought great musicians together in Philadelphia, but they weren’t immune to the complicated reality of the time.

“In Philadelphia, as in other cities, jazz and the jazz culture was the first time whites and blacks mingled on an equal basis,” she says. “And some folks did not like that.”

Clubs were harassed by the police, she says, and one called the Downbeat was even shut down. During December of 1956, police targeted a club called the Blue Note where the Miles Davis Quintet was broadcasting live on the radio. Police raided the venue, but the club stayed open after the owner said he saw what happened to the Downbeat and refused to close.

Many musicians used the famous Green Book to find places to eat and sleep that weren’t segregated. Published from 1936 to 1966, the Green Book was a “lifesaver” travel guide that helped black Americans navigate Jim Crow laws in the south and racial segregation in the north, she says.

“When you think about the music that was created during that golden age of jazz, these musicians, music that we will listen to for generations to come — they didn't even know where they could sleep that night,” she says. “It was horrible conditions under which they produced this beautiful music.”

Philadelphia is home to several Green Book sites, including six businesses that are still operating today, she says. Anderson’s favorite is Club 421 in West Philadelphia, where the interior hasn’t changed since the 1940s and visitors can stand on the same stage as Coltrane, Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday.

Musicians born and raised in Philadelphia took on injustice in their music, too. In the haunting 1939 protest song “Strange Fruit,” Holiday’s lyrics condemned racist lynchings.

Now a plaque honors Holiday outside the Philadelphia hotel where she often lived.

“When you talk about Billie Holiday it’s not just her legacy as a singer,” she says. “For me, as important is her legacy using her art to address the social issues of the day.”

Lynn Menegon produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Kathleen McKenna. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on March 10, 2020.