Advertisement

Here & Now's 2020 Election Coverage

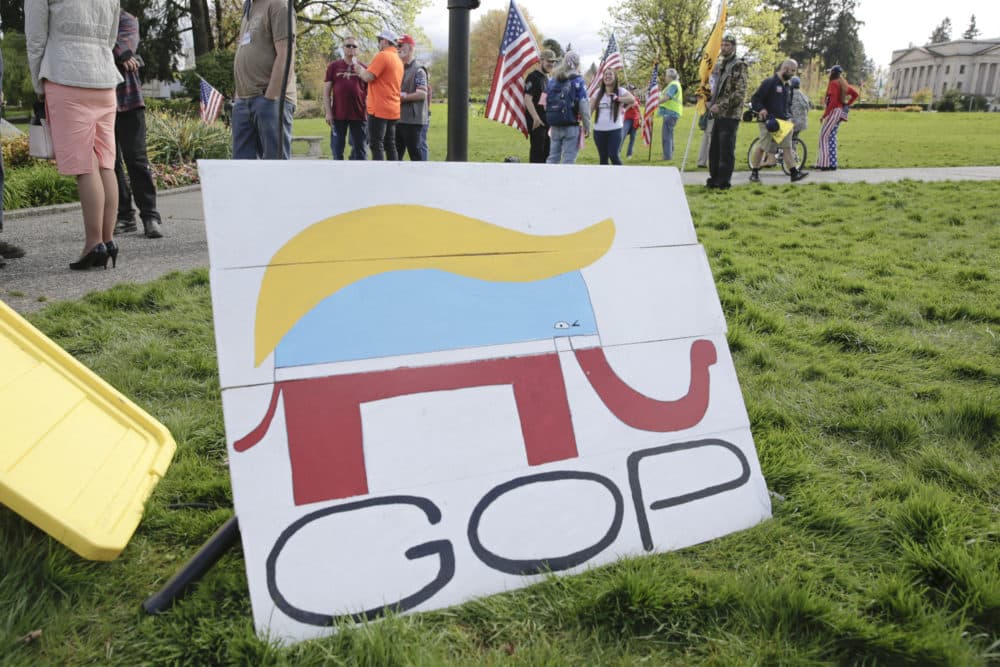

What's Ahead For The Republican Party, From GOP Insider And Lincoln Project Member Stuart Stevens

Last Saturday, when the Associated Press called the presidential race for Joe Biden, President Trump became the 10th sitting president to lose re-election.

Perhaps in any other year, Trump’s defeat would suggest a period of reflection and rebuilding for the GOP. Instead, Trump is refusing to concede the race — a move that has no precedent in American history — and the majority of Republican senators, save for a handful, seem to be sticking by his side.

Even for Stuart Stevens — a wily operative who has seen the best and worst GOP, running Republican campaigns in his home state of Mississippi for congressmen like Jon Hinson before graduating to clients like George W. Bush and Mitt Romney — the present moment is inconceivable.

“I mean I wrote a pretty bleak book about the Republican Party,” says Stevens, a contributor to the Lincoln Project, a super PAC created by once-upon-a-time Republicans dedicated to defeating Trump. “I would have never imagined [this].”

The “bleak book” is “It Was All A Lie: How The Republican Party Became Donald Trump.” In it, Stevens describes how Trump was the epiphany that made him realize all the principles he had thought the Republican Party stood for — personal responsibility, lowering the deficit, a tough stance on Russia, free trade — were nothing more than hollow “marketing slogans.” In reality, Stevens says, the Republican Party has become the party of “white grievance.”

It wasn’t always that way though, Stevens writes, at least not to the same degree. In 1956, Dwight Eisenhower won 39% of the Black vote; it wasn’t until 1964 when Barry Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act that Black support for the Republican candidates fell to 7% where it has remained more or less since.

After Mitt Romney lost to Barack Obama in 2012, Stevens recounts, Reince Priebus, then the chairman of the Republican National Committee, commissioned an “autopsy report” on what had gone wrong. Among its findings were that traditionally reliable Republican strongholds such as New Mexico and Virginia were increasingly voting Democratic as the electorate shifted from being 88% white in 1980 to 72% white in in 2012.

“If we want ethnic minority voters to support Republicans,” the RNC report concluded, “we have to engage them and show them our sincerity.”

The report was not only presented as a political necessity, Stevens recalls, but as a “moral mandate.”

Advertisement

“That [if] you want to earn the right to govern this big, changing, confusing, loud country, you need to be more like the country,” he says.

But it came as an “almost audible sigh of relief,” Stevens says, when Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, “like, ‘Oh thank God we can just win with our old coalition of white folks.”

Stevens believes the Republican Party will continue to be the “party of white grievance” until it’s clear it’s no longer a winning strategy. But that might take some time: According to Stevens, the Republican Party “is like the subprime mortgage crisis. It’s a lot easier to predict how it ends than when it ends.”

For the foreseeable future, Stevens sees Trumpism as “alive and well,” and that it will continue “to dominate the Republican Party.”

That’s because “there is no viable anti-Trump movement in the Republican Party,” he insists. “There’s not.”

Meanwhile, Stevens predicts that Democrats will win Texas in 2024, after which “it’s over, lights out” for Republicans. After that, he says, Republicans will try to abolish the Electoral College in 2030. But while Republicans work on kicking their Trump habit, Stevens says the country is in for a period of “center-left governance.”

Stevens’ efforts to cement that future through his work with the Lincoln Project have drawn the ire of some former clients, as well as considerable skepticism from those on the left. After all, Steven’s former boss, Mitt Romney, was a frequent guest and fill in for a radio talk show hosted by the late “shock jock” Jay Severin, who was fired for saying “kill all the Muslims.” Surely the “never-Trumper” bears some responsibility for getting Trump elected in the first place?

Yes, Stevens is quick to admit. He bears much blame, but explains his personal evolution like this: “I worked for George [W.] Bush. I went down to work for him in ‘99 in Austin. We believed that ‘compassionate conservatism’ was the future of the party… and I think that a lot of us thought that a lot of us, certainly I did, thought that the side of the party we were on was inevitable. That we were the dominant gene and what I would call ‘[the] dark side’ was [a] recessive gene.”

He pauses.

“I think I was wrong.”

Stevens’ mea culpa, while perhaps disingenuous to some, is nevertheless rare among most Republicans who he says have clung to Trump for no other reason than fear of losing to the Democrats.

In “It Was All A Lie: How The Republican Party Became Donald Trump,” Stevens writes that asking “the Republican Party today to agree to a definition of conservatism is like asking the New York Giants fans to have a consensus opinion on the Law of the Sea treaty. It’s not just that no one knows anything about the subject; they don’t remotely care. All Republicans want to do is beat the team playing the Giants.”

Stevens says his thinking has even evolved slightly since writing those lines. Now, he says he thinks Republicans are simply afraid of being ostracized in the Republican Party, which he describes as “a club,” or “life imitating high school.”

He does give Trump credit for one thing.

Trump “sensed that the Republican Party really didn’t believe in anything and if he came in and promised them power, they would go with a guy who was against everything they said they were for,” he says. “He was right.”

This segment aired on November 12, 2020.