Advertisement

'Fernandomania' 40 years later: How Fernando Valenzuela captivated baseball fans for decades

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcasted on Aug. 11, 2023. Find that audio here.

If you were a baseball fan in the '80s, you knew about "Fernandomania."

That was the word for the spectacle and excitement surrounding Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, who made his first start for the team 40 years ago this month. Decades later, he remains a Mexican American icon.

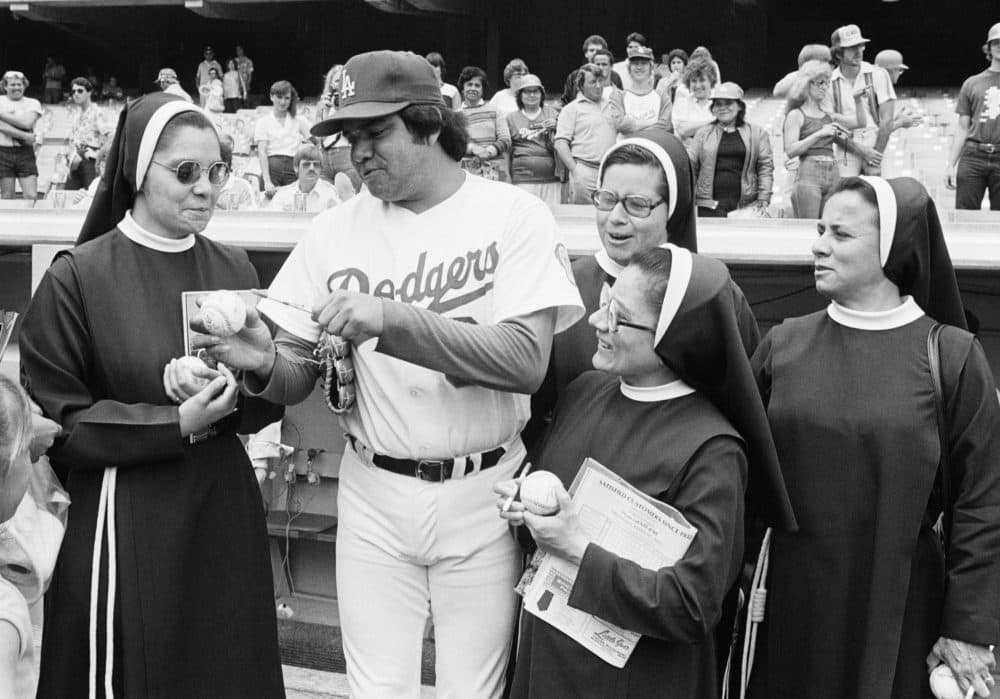

Legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully has described the frenzy around the star pitcher as a “religious experience.”

Fans were immediately captivated by the portly pitcher from Sonora, Mexico. They’d line up at the stadium to watch his “dramatic” windup, Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano says. Arellano is part of the newspaper’s “Fernandomania @ 40” documentary series.

Winding up on the mound, Valenzuela would extend his arms up as high as possible, hands in the air, eyes toward the sky, before unleashing an “explosive delivery to home plate,” Arellano says.

Valenzuela — nicknamed “El Toro” by doting supporters — had the added touch of being a left hander, a rarity among pitchers. He mastered the screwball, a pitch that very few players can perfect because of how taxing it is on the throwing arm, Arellano says.

“But Fernando, for those first couple of years, he was like Zeus,” he says, “throwing thunderbolts down to home plate and just slaying all the competition.”

As a young Mexican American in Southern California at the time, practicing Valenzuela’s delivery became a ritual in the community, Arellano says. Dads and uncles would challenge the kids to competitions to see who could throw their arms the highest or roll their eyes “up to heaven” the most, he remembers.

Valenzuela’s first start for the Dodgers in April of 1981 was a shutout win against the Houston Astros — a moment that marked the start of “Fernandomania.” Los Angeles went wild.

“Nothing has been like this in sports ever since,” Arellano says.

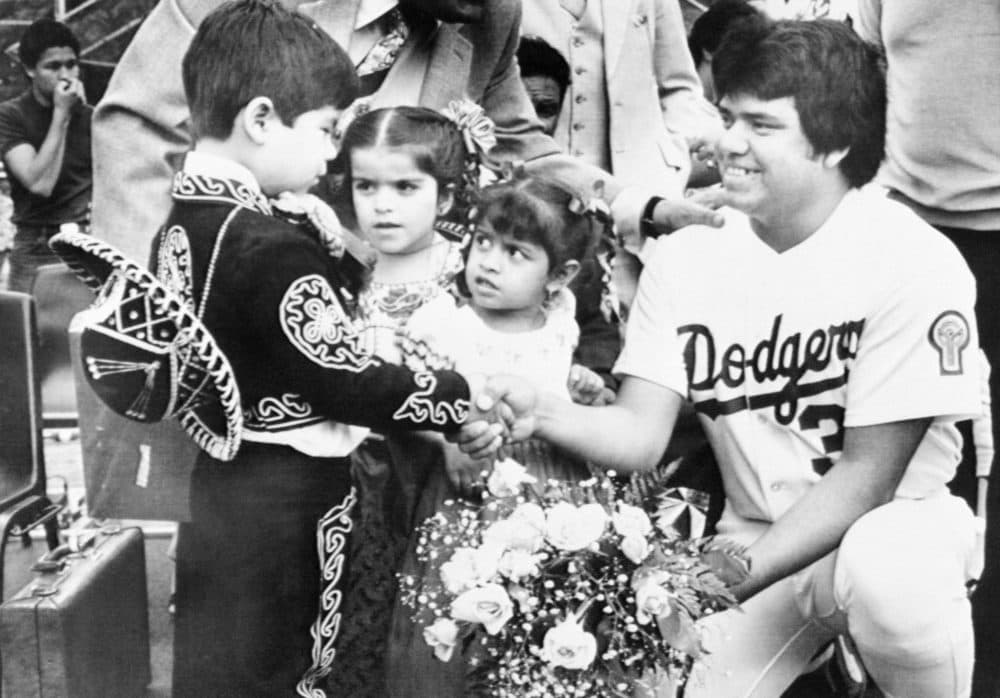

In the early 1980s, Mexican Americans started to become the biggest ethnic group in Southern California, but were “still kind of seen as strangers” despite living in the area for generations, he says. At the same time, the Dodgers had failed to produce a World Series win since 1965 and weren’t actively embraced by the Mexican American community, he explains.

Then in walks Valenzuela, outfitted in thick bomber glasses, who was “pudgy, you know, he looks like your uncle,” Arellano says — and everyone fell in love.

“Specifically for Mexican Americans, we take him to heart more than anyone,” he says, “because for the first time and maybe ever in the United States, everyone wants to be a Mexican.”

He checked off career milestones effortlessly: In his first season in the major league, he won both Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards, as well as helped carry the team to a World Series championship win.

“More importantly for Mexican Americans, we have not had a Mexican who has been as popular among the rest of the United States ever since,” Arellano says.

Four decades later, Mexican Americans still feel nostalgic for the peak of the Valenzuela years. But Arellano says he’s “skeptical of saviors” because Mexican Americans must find confidence within to navigate life in the United States.

“The salvation was us,” he says.

Alex Ashlock produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on April 16, 2021.