Inside One Jail's Health Care Problems And ‘Culture Of Impunity’

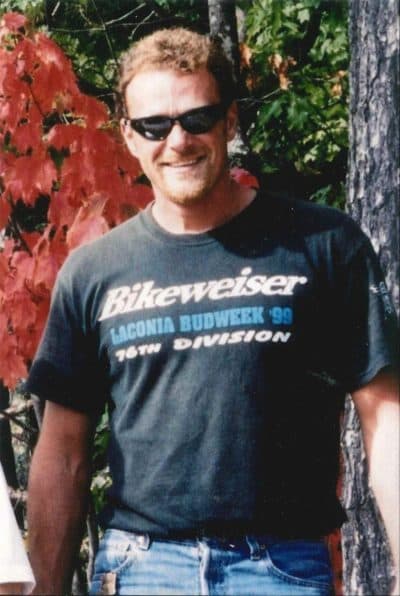

In the Essex County jail infirmary, corrections officers tackled Richard Pike to the floor last May. He struggled, face-down, with several men on his back. They believed he was being combative.

In fact, Pike was dying. The Farmington, N.H., construction worker had been clutching his chest and begging for oxygen, jail records show. A nurse tried to give him a nebulizer breathing treatment, but he kept pushing it away. That’s when guards took him to the ground and cuffed him.

“I can’t breathe, you need to help me,” Pike, 51, told officers, according to jail reports.

They eventually unshackled him, and a nurse started Pike on oxygen. He died within minutes of arriving at a hospital.

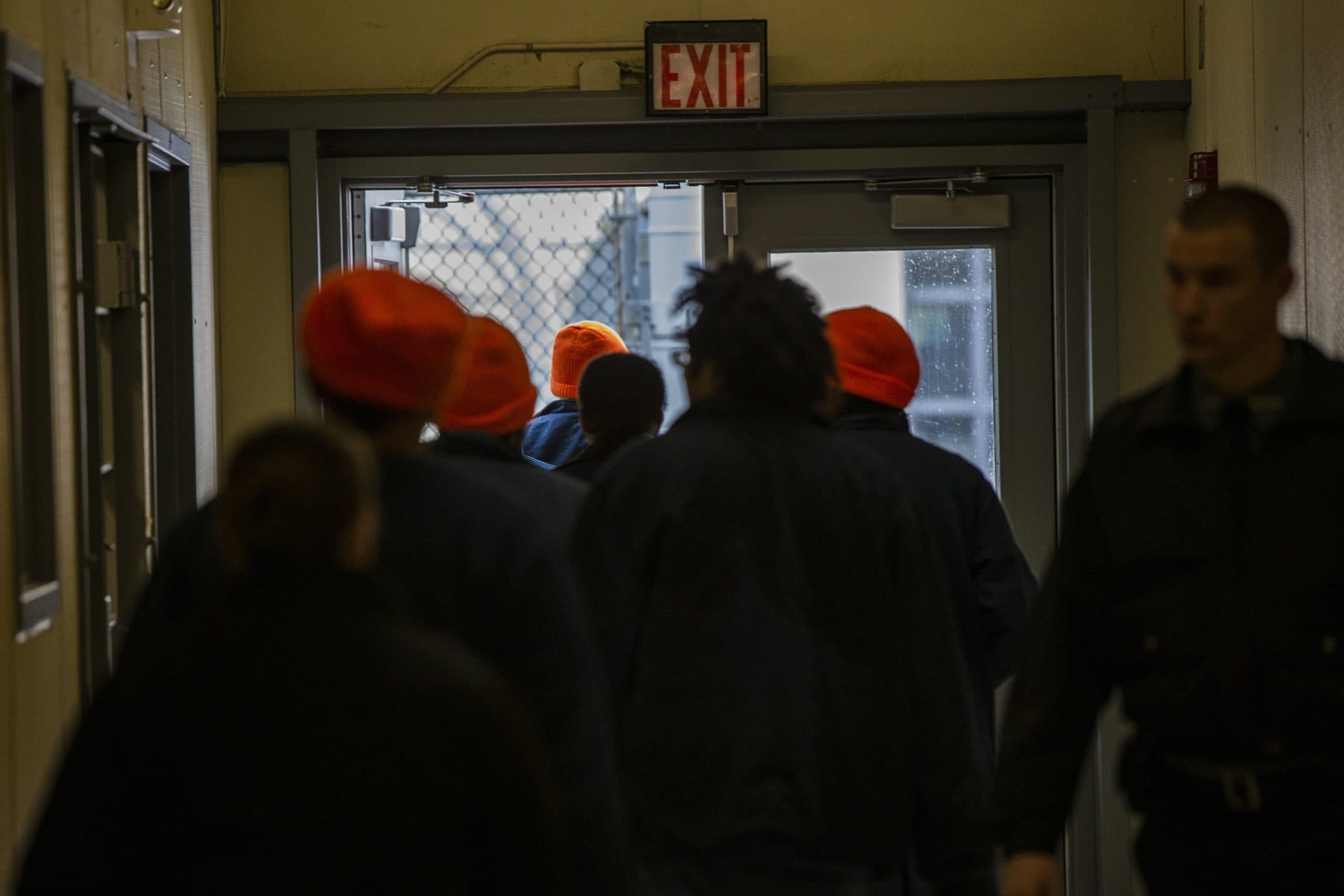

Corrections officers play a leading role in how medical care is handled at county jails in Massachusetts. They can save lives in emergencies and pass vital information on to medical staff. They also can delay care. A WBUR investigation found that when guards ignored sick inmates or failed to react to serious medical complaints, it often led to further suffering, and even deaths.

“Jails and prisons are there to confine and punish,” said Nancy Neveloff Dubler, professor emerita at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and an ethics specialist in jail care. “Health care is there to care for and to cure. Those are antithetically opposed goals.”

As the coronavirus infiltrates jails, guards are on the front lines of a new health crisis that endangers themselves as well as inmates, many of whom are awaiting trial and not yet convicted of a crime.

The Essex County jail in Middleton — a sprawling facility not far from Boston’s wealthy northern suburbs — stands out among others in the state for its history of violence and turmoil. Pike is one of 23 people who have died under the custody of Essex sheriffs in the past decade, WBUR found. Fifteen died for medical reasons.

Officers at Essex played a role in exacerbating some medical emergencies, according to a review of public records, state police investigations and attorney interviews.

Kevin Coppinger, a former Lynn police chief who became Essex sheriff in January 2017, said he reviewed the Pike case.

“They did restrain him,” Coppinger said. “And then as soon as they recognized the fact that, ‘Whoa, wait a minute, this is not going in the right direction,’ they removed the restraints and medical staff immediately provided medical care.”

Asked why guards used force on Pike, and why no one initially seemed to recognize his health emergency, Coppinger largely defended the staff.

“Was it perfect?” Coppinger asked. “You know, it could've been better.”

One of Pike’s sisters, Nancy Marcotte, can’t understand what happened.

“If they had called an ambulance when he first said he couldn't breathe and was begging for help, he might still be alive,” she said.

Editor's Note: Above is a recording of the May 2, 2019, call from Essex County jail for Pike, who died. WBUR obtained it through a public records request.

There have been seven deaths on Coppinger’s watch, mostly with medical causes.

Coppinger oversees about 1,300 inmates and a $55 million budget. He said he embraces transparency, but Essex is one of the most secretive jails in the commonwealth when it comes to disclosing details of the deaths, WBUR found.

The sheriff’s office refused to provide both the names of those who had died and their causes of death, other than suicide. Essex officials released some records after WBUR’s lawyer threatened to sue, under public records law.

'Ignored Him To Death'

Essex guards were in charge of transporting 29-year-old Sam Dunn in January 2016 to a substance-abuse treatment center in Bridgewater, about an hour from Middleton.

Dunn was one of hundreds of people in Massachusetts struggling with addiction and civilly committed to treatment centers by judges.

He was born in Colombia with fetal alcohol syndrome and spent most of his infancy in an orphanage, according to Tony Dunn. He and his former wife adopted Sam at eight months.

He grew up in Saugus, played soccer and joined the Cub Scouts. But Sam Dunn had behavioral struggles in school and later started using drugs. He did stints in rehab centers and jail for parole violations.

Dunn had been to the Essex County jail before. But this time, he fell through the cracks.

People typically go through an intake and assessment process when booked into jail. But Dunn wasn’t going to stay at Essex; it was a temporary stop en route to Bridgewater.

Corrections officers put him in a group holding cell at about 5 p.m. on Jan. 6, and never entered him into the intake system.

Video of Dunn obtained in a records request shows him banging on the door of the cell to get guards’ attention. He paces and lurches from one side of the room to the other. He strips off his shirt, and at one point his whole body shudders as he grabs his chest. Later he slouches, in and out of a stupor.

Dunn had swallowed a large amount of opioids before being taken into custody, according to a lawsuit filed by his family.

But corrections officers, as seen on the video, didn’t watch Dunn closely or realize he was in distress. Two of them loaded Dunn, unsteady on his feet, into a transport van at 6:30 p.m. As they drove, the guards heard Dunn snoring loudly, the lawsuit states.

Loud snoring can be a sign of suppressed breathing, a symptom of an overdose.

At 9 p.m., the van arrived at the Bridgewater treatment center, which was in lockdown due to a riot. Dunn continued to snore loudly as officers parked in the lot and waited.

“They are, in fact, talking on their cell phones,” Howard Friedman, the Dunn family’s lawyer, said. “They are listening to the radio.”

A Bridgewater lieutenant asked the officers if anyone needed medical attention; they said no, according to the lawsuit.

At about one in the morning, the officers opened the van door. Dunn had slipped from his seat to the floor and vomited, Friedman said. He wasn’t breathing, and his skin had turned blue. It had been six hours since the officers loaded Dunn into the van. The lawsuit said he died of an opioid overdose.

Had Dunn been checked into Essex’s custody, “he would have gone through an admission process and seen a doctor, and he’d be alive today,” Friedman said.

The officers in the van, Patrick Barry and John Nguyen, still work at the Essex jail and did not return calls for interviews. It’s unclear if they were disciplined, because those records are not public. Friedman said a grand jury reviewed the case, and determined it would not charge them with a crime.

Essex County did not include any reference to Dunn in a list of deaths in custody provided to WBUR. His death, chronicled publicly at the time by WCVB, occurred under the prior sheriff. But Coppinger acknowledged his office “probably should have” included Dunn on the list.

The sheriff’s department also failed to report Dunn’s death to the Department of Justice, an Essex official confirmed. That means his death has never been counted, either locally or nationally.

Tony Dunn, Sam’s father, said the sheriff at the time, Frank Cousins Jr., called him when Sam died.

“He actually gave me a big song and dance about how they tried so hard to save him,” Dunn said. “And it was all crap. It was all made up on the spot. They didn't do anything.”

Coppinger has since installed cameras in transport vans. But that’s no solace for Dunn’s father. He said he feels betrayed by the Essex County Sheriff’s Department.

“They just basically ignored him to death,” Dunn said. “I can't tell you how that feels.”

History Of Excessive Force Complaints

A review of lawsuits against the Essex County jail, its employees and its medical staff over the past decade shows a slew of disturbing complaints. Many detail injuries that were not treated or were sustained at the hands of guards.

One man’s broken jaw allegedly went untreated for three days after a fight with other inmates left him in pain and in need of dental care. His lawsuit claimed corrections staff threatened to put him in solitary confinement if he didn’t stop complaining.

Another man sued after guards allegedly beat and sexually assaulted him while he was shackled. The lawsuit was dismissed after jail surveillance video of the incident apparently went missing.

And a former inmate claimed that guards inappropriately used security dogs to attack and bite him and other inmates. Last year, the sheriff’s department settled with the man for $15,000, Boston-based Prisoners’ Legal Services stated.

Sheriff Cousins oversaw the jail for most of these incidents. A former state representative and car dealership owner, he was first appointed by Gov. William Weld in 1996, after the sheriff before him pleaded guilty to taking illegal kickbacks. Cousins would go on to be elected sheriff three times, serving for two tumultuous decades marked by injuries, deaths and financial trouble.

Now president of the Greater Newburyport Chamber of Commerce & Industry, Cousins declined to be interviewed for this report.

Prisoners’ Legal Services has examined a host of complaints about Essex. It found allegations by inmates of excessive use-of-force by guards that resulted in brutal injuries — from a fractured skull to broken limbs. And, when inmates were injured, lawyers with Prisoners’ Legal Services said the jail’s internal investigations were often cursory.

Separately, two accreditation audits of Essex by a national corrections association, in 2009 and 2012, show a total of 658 uses of force. Cousins’ office responded in the audits that none of those was inappropriate.

Share your story or send our investigative team a tip. Plus, sign up to get WBUR investigations in your inbox. And listen to this series on your smart speaker.

The current sheriff, Coppinger, said he’s working to improve the jail environment.

Asked whether he was aware of the history of excessive-force complaints when he took the job in 2017, Coppinger said he was not. He said he has hired new leaders and expanded training for officers and supervisors, with an emphasis on in-person classes.

“Sometimes you’ve got to use force,” Coppinger said. At the same time, he said he hopes to “change the culture here — culture of the jail, culture of the staff. Teach them what is professionalism.”

Broken Back, Broken Nose And 15 Stitches

In July of 2012, Andrew Nascarella lay in a pool of his own blood at Essex’s Middleton House of Correction, after a guard punched him in the face.

Nascarella, a 28-year-old construction worker with a history of mental illness and serving time for larceny, was being held in the jail’s segregation unit.

At one point, he refused an order to return to his cell, because he wanted to see a supervisor. Corrections officer Travis Mustone walked across the unit to confront Nascarella. Suddenly, Mustone grabbed the handcuffed inmate from behind and hurled him to the ground, according to court records and surveillance video provided to WBUR by Nascarella’s lawyer.

Mustone and another guard struck him. Mustone would later say in a deposition that he feared Nascarella would hit him with his shackled hands and that Nascarella was resisting — yanking his arm away.

Nascarella screamed in pain. He told a nurse, Karen Sindoni, his back was seriously injured, Nascarella’s lawsuit against the Essex County Sheriff’s Department and the jail medical provider stated.

Yet Sindoni did not take standard measures to stabilize his back, such as putting him on a backboard, said Jesse White, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services who represented Nascarella. Some corrections officers suggested to Sindoni that Nascarella go to the hospital by ambulance, but she told them to take him in a squad car, White said.

Nascarella’s back was broken. So was his nose, and his face needed stitches. He stayed at the hospital for 20 days.

“This incident resulted from a pattern and a culture of violence at the facility,” White said, and “a culture of impunity that resulted from failures in supervision and investigation.”

Sindoni, who worked for NaphCare Inc., a private, for-profit company that provides healthcare in jails, declined to comment. She now works at a nursing home.

Essex’s superintendent at the time, Michael Marks, reviewed the officers' use of force on Nascarella — and found it was justified, according to court depositions.

“This incident resulted from a pattern and a culture of violence at the facility ... a culture of impunity that resulted from failures in supervision and investigation.”

Jesse White

But White said the investigation was woefully inadequate. The officers were never interviewed, she said, and Nascarella’s injuries were not photographed, in a breach of standard practice.

The guard who threw Nascarella to the ground, Mustone, had been accused five times before of excessive use-of-force on inmates, and faced no discipline for them, according to the review by Prisoners’ Legal Services. He is still an officer at the jail and did not return calls seeking comment.

Marks, the longtime superintendent who ran unsuccessfully against Coppinger for sheriff, has retired. He did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2015, the sheriff’s department settled Nascarella's lawsuit for $85,000. NaphCare, the medical provider, agreed to a separate — secret — settlement, according to White.

But Nascarella’s experience inside the Essex jail, White said, will never leave him. She said the incident exacerbated his mental illness.

“That's really awful for the people who are incarcerated and who are traumatized,” she said, “and who then return to our communities struggling with that trauma.”

This segment aired on March 26, 2020.