Advertisement

In Mass., Many Small Gas Leaks Add Up To Big Consequences For The Environment

Maybe it's because you couldn't see it that one of the biggest environmental disasters since the 2010 BP oil spill recently came and went with little news coverage.

A mega-leak that erupted east of Los Angeles in October sent a plume of methane gas into the atmosphere for nearly four months before it was capped in mid-February. Its effect has been compared to burning nearly a billion gallons of gasoline.

Methane is a major contributor to global warming, and it's the main component of natural gas, which means it's likely to play a big role in New England's energy future. And we have leaks here too, and those leaks have consequences.

Small Gas Leaks Are Strikingly Common

To be sure, what's happening in Massachusetts is minuscule compared to what happened in Aliso Canyon, east of LA. That was a blowout in a high-pressure underground storage field. And there's nothing like that here.

Yet you might be in for a surprise were you to drive down Route 9 in Wellesley in a van Bob Ackley calls "Ghostbuster."

"The gas company is working right up ahead of us right now repairing a leak," Ackley said on a recent drive. "They've been here for days."

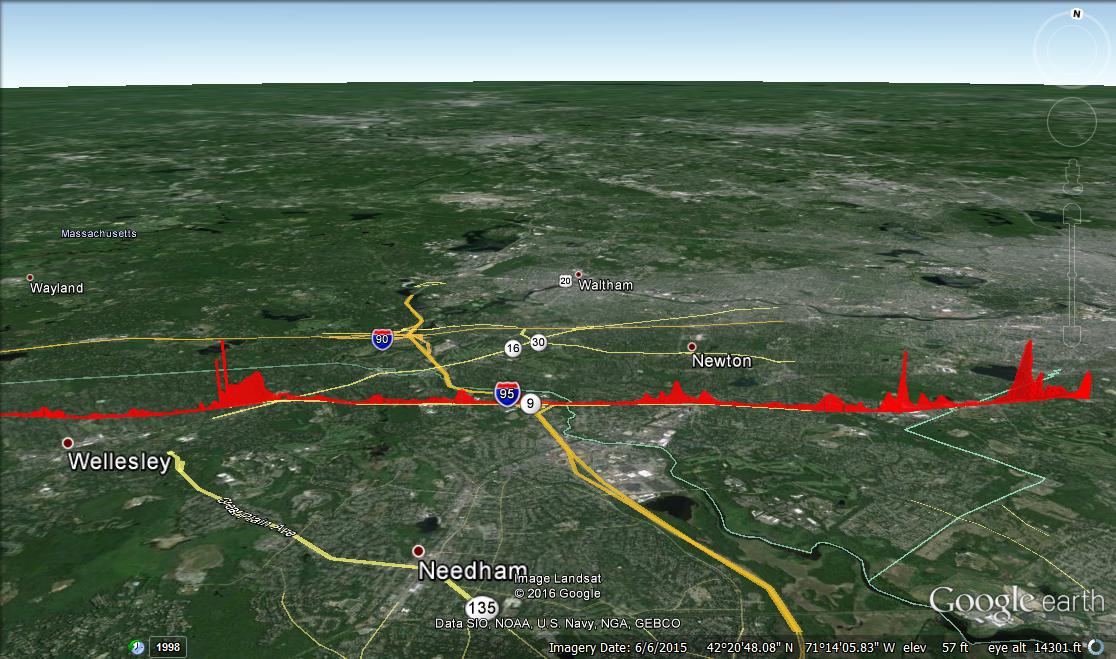

Ackley calls his company Gas Safety USA, and we recently took his van for a drive over an underground gas line that runs all the way into Boston.

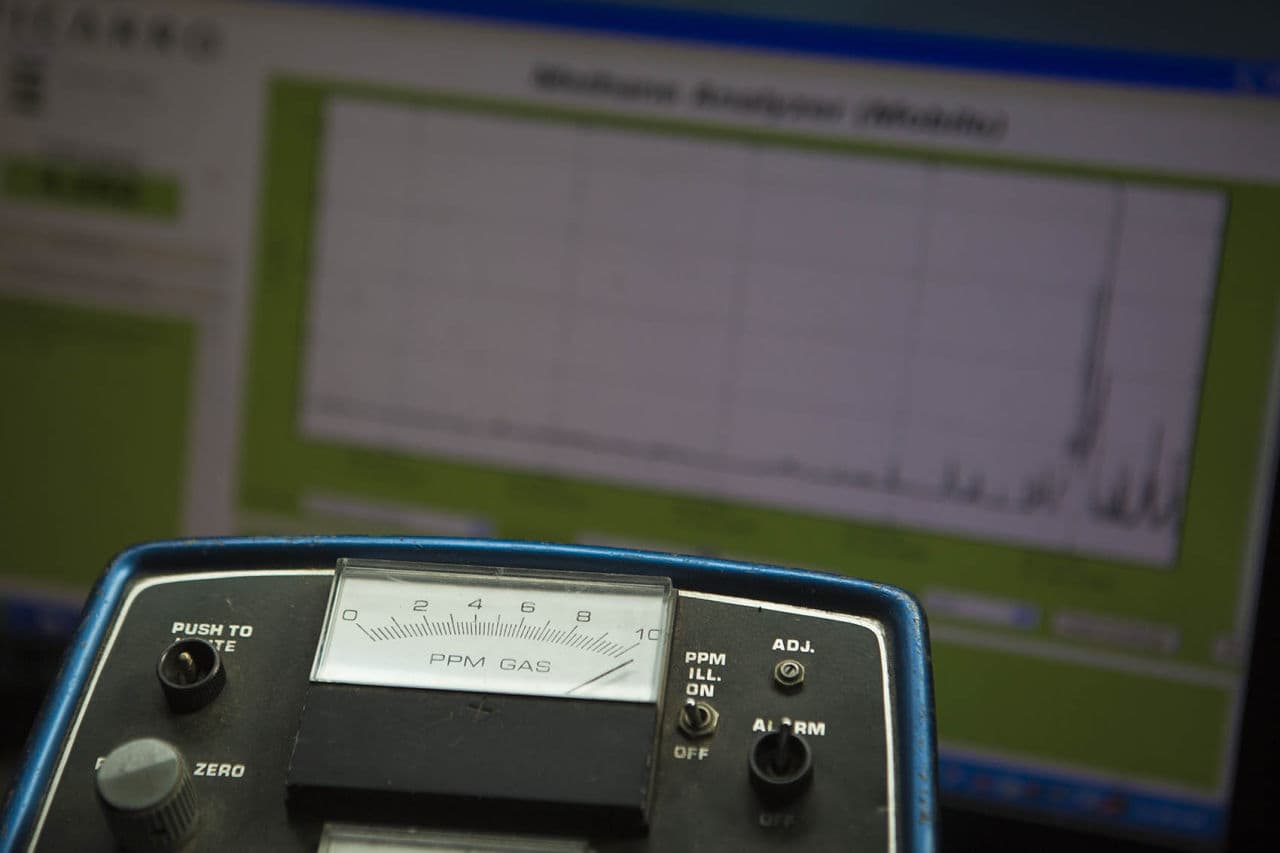

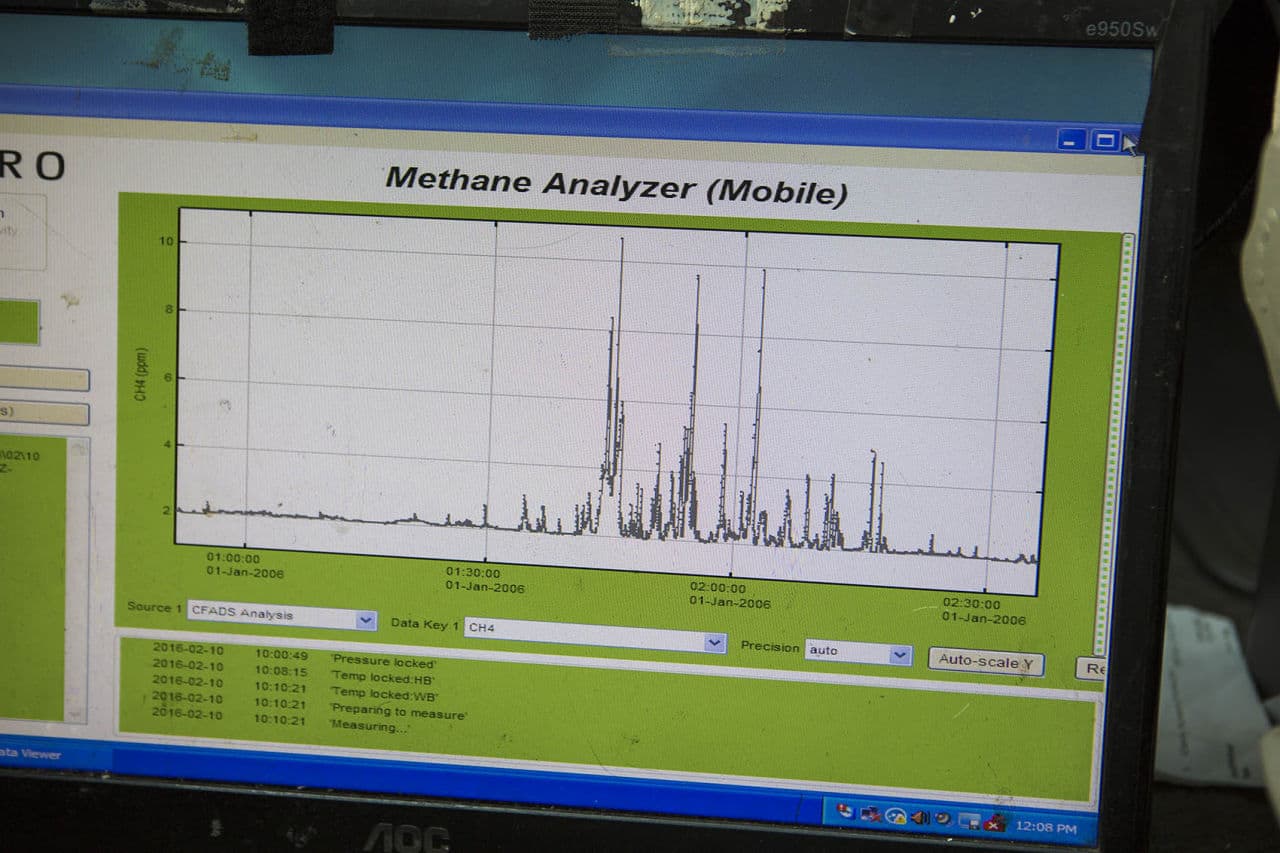

Equipment at the front of his van collects air close to the pavement and streams it into sophisticated, high-precision analyzers that detect and map methane leaks on GPS. A high-pitched alarm alerts Ackley to leaks.

On our drive, we found a leak that measured 4.5 parts per million — double the normal background level of methane. Close to Wellesley Center we picked up another reading of 10 parts per million, which is five times the normal background level.

Ackley, a former gas company investigator, says Route 9 leaks are routine. He's been driving over them for 30 years.

"So see we have some patches here," Ackley says, pointing to a roadway tattooed with signs of previous leaks. "This is where repairs were made. They're 12 to 24 feet across. You can see continual drill holes."

Take a look next time you drive Route 9 from Brookline to Wellesley. You can't miss the drill holes in the pavement — the telltale sign of a search to pinpoint leaks before repair.

Ackley detects mostly small leaks, most of them posing no danger to humans or property, all unseen but strikingly common, wasteful and damaging to the environment.

Methane Is 'Like CO2 On Steroids'

Back in 2012, Ackley and Boston University professor Nathan Phillips traveled all of Boston's roads and mapped 3,356 methane leaks in the city's gas mains.

"And we know that in the towns and suburbs around Boston, and in fact throughout the entire Eastern Seaboard, this is a problem," Phillips says.

A problem that amounted to the direct loss into the atmosphere of 3 percent of all the natural gas consumed in 2012. That's according to Phillips and his colleagues at Harvard, Duke and Stanford universities. If anything, that number is conservative, Phillips says. And if you think 3 percent is small, think again.

"[Methane] traps heat more efficiently and creates that blanketing effect over the Earth's atmosphere and holds the heat in."

Nathan Phillips

"Methane on a per mass basis is many times more powerful than carbon dioxide," Phillips says. "It traps heat more efficiently and creates that blanketing effect over the Earth's atmosphere and holds the heat in."

Over a 20-year span, methane is 87 times more damaging to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. So even small leaks are insidious.

"If it's leaked, it's like CO2 on steroids," Phillips says.

So the effect of the 3 percent gets magnified. According to Phillips' estimate, methane leaked from gas lines accounts for 10 percent of all greenhouse gases emitted in Massachusetts.

Numbers like that challenge the reputation of natural gas as a clean fuel. But the industry takes exception to those numbers. Tom Kiley, of the Northeast Gas Association, says methane leaks from gas mains are insubstantial.

"We've seen a significant improvement throughout the natural gas system in the commonwealth of the amount of methane escaping from our system," Kiley says, citing state reports that say methane accounts for a little more than 1 percent of all greenhouse gases in Massachusetts.

Advertisement

Kiley credits the modernization of an old system of cast iron and bare steel pipes.

"As this aging infrastructure is replaced with new pipe, with plastic pipe, it does result in less leaks and that is commensurate with the amount of reduced emissions that we're seeing throughout the commonwealth on the natural gas system," he says.

Death By A Thousand Cuts

But both Phillips and Ackley point out that they reached their numbers by actual measurements. Which brings us back to the methane blow out in California, where Ackley and Phillips monitored the mega-leak.

"The scale of this thing is nuts," Rachel Maddow of MSNBC said in a report on the catastrophe. "State air quality regulators estimate that the leak is releasing so much methane per hour that this one leak basically accounts for 25 percent of all the daily greenhouse gas emissions for the entire state of California."

The effect is huge. But consider the cumulative effect of so many small gas leaks across Massachusetts, each insignificant compared to California's. The cumulative threat may be as invisible as the methane itself.

In biology it's known as "destruction by insignificant increments." Elsewhere, it's called death by a thousand cuts — every leak takes its toll.

This segment aired on February 29, 2016.