Advertisement

Ahead Of Sentencing In Meningitis Case, Questions Around Verdict Slip Remain

Resume

Only the jurors know whether they actually acquitted pharmacist Barry Cadden on charges of second-degree murder.

Cadden was at the center of a deadly outbreak of fungal meningitis linked to contaminated steroid injections prepared by his company, the New England Compounding Center. More than 60 people died.

In March, he was convicted of racketeering and mail fraud, but was acquitted on 25 second-degree murder charges, which could have sent him to prison for life.

Except the verdict form suggests jurors were actually divided when they were supposed to be unanimous. And Judge Richard Stearns, who will sentence Cadden in a federal courtroom in Boston on Monday, accepted their verdict without making sure all 12 had agreed.

In the three months since the verdict, Stearns has refused to follow the customary practice of local federal judges to release the identities of the jurors soon after trial.

'A Gigantic Mess'

"It is a gigantic mess," says trial and appellate lawyer and legal writer Harvey Silverglate. "I think that's the technical, legal term I would use to describe it."

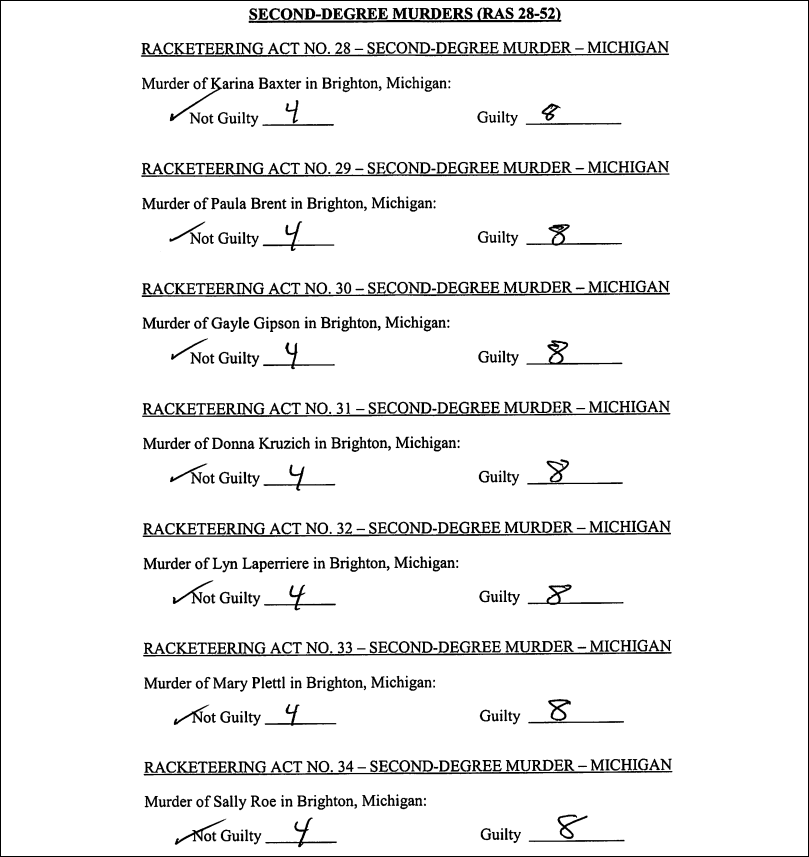

Other experts and observers describe what the jurors did as astonishing: Instead of simply checking off "guilty" or "not guilty" on the verdict form, when jurors considered the second-degree murder charges they also wrote how many jurors thought Cadden was guilty and how many thought he was not guilty for each charge.

Nine guilty, three not guilty for some of them. Eight guilty, four not guilty for most of them. That's hardly unanimous as federal verdicts require.

And what the judge did when he saw the verdict form with those numbers was just as astonishing, says NYU Law Professor Stephen Gillers. He's an expert on judicial ethics and law governing trials.

"It was incumbent on the judge recognize immediately that he needed to consult with counsel," Gillers says.

But Judge Stearns did nothing of the sort. In fact, he did not tell the lawyers at all before the verdicts were read.

"The verdict on certain counts was unclear," says Silverglate. "The only way to clarify it was to bring the jurors back in the courtroom and ask them what they meant."

But the judge did not do that either. He simply accepted the verdicts of not guilty.

Yet if the jurors were not unanimous, then they did not have a verdict. And if they did not have a verdict they weren't finished deliberating. If they were hopelessly divided, they did not report it. So, arguably, the judge discharged the jurors before they were done. And it's too late to bring them back.

"The judge obviously must have realized there was a problem," Silverglate says. "He sloughed it off and everyone is living with the consequences."

Hiker and outdoorsman Bill Thomas is one of the 700 people across the country who received a tainted injection and got sick. He says walking 100 yards now causes great pain. He's outraged that the judge "didn't bother to ask the jurors a couple of questions" about what they meant to say.

"He seems more concerned about the jury's discomfort than the fact that hundreds of people are sick and their lives have been changed and dozens of people are dead," Thomas says.

The maximum penalty on the counts for which Cadden was convicted is 20 years. But trying to make the best out of the judge's conduct, prosecutors argue that he should consider jury's tell-all verdict form at sentencing. It shows that the majority of jurors voted guilty on the murder charges, after all, and guilty verdicts would have carried a maximum penalty of life in prison.

So prosecutors are proposing a sentencing standard based on preponderance of evidence, not the trial standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

So even though Cadden was acquitted, he could still be punished as if he had been found guilty.

This too comes as a consequence of Stearns' response when the jurors handed him their seemingly contradictory verdict form. And Stearns' insistence on keeping the jurors' identities a secret has also kept a secret of whether they actually acquitted Cadden.

"The judge's reason or rationalization is quite transparent. I think he doesn't want the press to interview the jurors because it could embarrass the judge," Silverglate says.

'The Presumptive Rule Is Disclosure'

"The obligation of openness exists independent of whether people are going to be applauding the verdict, applauding the process, or criticizing the verdict or criticizing the process," says Robert Bertsche, general counsel to the New England Newspaper and Press Association. "The fundamental principle is that this information belongs to the public so that the public can make independent judgments about how the system is working."

The ruling precedent in the 1st Circuit, which includes Massachusetts, has long been that the identities of the jurors are "presumptively public." By practice, as former federal judge Nancy Gertner explains, the names and the addresses of the jurors have customarily been released seven to 10 days after trial, or sooner.

"The presumptive rule is disclosure unless there is a reason that a judge can justify."

Nancy Gertner, former federal judge

"The presumptive rule is disclosure unless there is a reason that a judge can justify," Gertner says.

To withhold the names, judges are required to show "particularized findings" of a "significant threat" to "the judicial process itself" — such as the safety of jurors.

Such findings have not been made by Judge Stearns to justify holding the jury list in the case of Barry Cadden. A lawyer for WBUR pointed that out in a recent motion to unseal the jury list. The judge responded that he would release the list, but not until after sentencing. He further stated that he would release the jurors names and their towns or cities of residence — but that's not the same as an address.

For instance, in the case of a Bob Smith, or a Barbara Smith, of Boston, a full address may be necessary to identify the individual.

"Giving the name and the city of Boston without a street address is really giving the illusion of access without the actual impact of access itself," Bertsche says.

In a motion for reconsideration, WBUR argued last week that the ruling precedent called for the release of jurors names at the end of the trial, not the end of sentencing, and for the release of both names and addresses unless there was a finding of significant threat. The trial of Barry Cadden has involved neither terrorists or mobsters, but a pharmacist.

In an order denying WBUR's motion, Judge Stearns seemed to dismiss the 1990 opinion that has been considered the ruling precedent and the basis for the practice of releasing jury lists soon after trial. He called it "a decades-old decision" written "in a more innocent age."

And without further reasoning or argument, he wrote: "In the turbulent times in which we now live, I would no more consider ordering the public disclosure of a juror’s home address than I would my own."

Gertner, who has co-authored "The Law of Juries," now in its ninth edition, says that as far as she knows the law has not changed.

"The law of this circuit is there's presumptive access," she says.

A battle that erupted with an astonishing verdict form and a judge's astonishing failure to act is likely to rage Monday afternoon, but before anyone can find out who the jurors are to ask what were they thinking.

This segment aired on June 26, 2017.