Advertisement

CLIMATE CHANGE IN MASS.

A Barrier For Boston Harbor: UMass Team Studies Flood-Protection Plans

Resume

With sea levels rising, a team at the University of Massachusetts Boston is researching harbor barriers to protect the city from flooding.

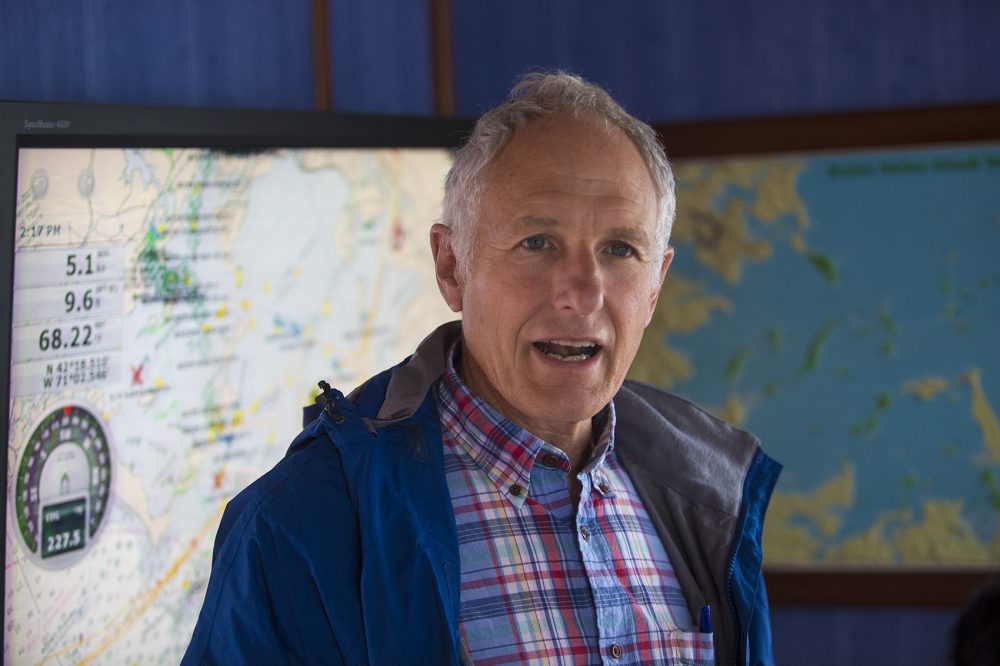

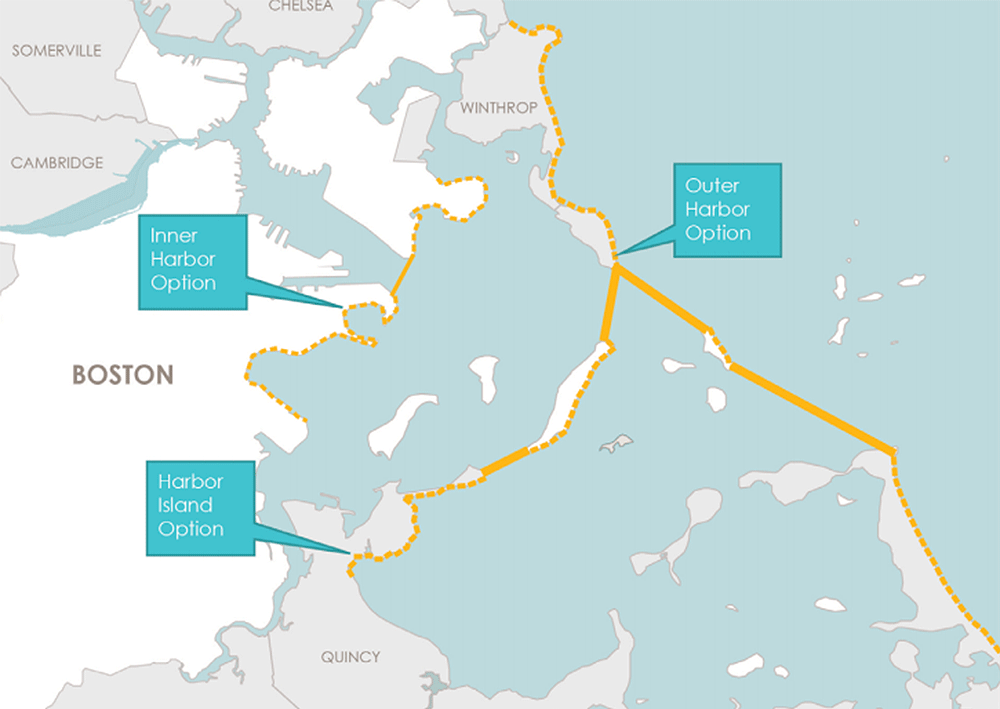

The team, led by Paul Kirshen, a professor of climate adaptation at UMass' School for the Environment, is weighing three harbor barrier configurations:

- The smallest would connect Logan Airport in East Boston with Castle Island in South Boston, protecting the city's inner harbor and downtown from tidal flooding.

- The medium-sized solution is a barrier from Deer Island, in the harbor, to Quincy, which would wall off all of Boston's neighborhoods.

- The largest of the proposed harbor barriers would protect not just Boston, but also Weymouth, Hingham, Quincy and Hull.

The UMass team has a big question to answer: Should the city start taking steps to build a barrier around the heart of the Massachusetts economy?

Or is the idea dead in the water?

If the city decides it wants to go forward, it could take decades — and untold billions of dollars -- before a harbor barrier is built.

The barrier study was recommended in the city's Climate Ready Boston report last year. The report says a barrier could work well in Boston Harbor, with its relatively shallow waters, and publicly owned land along the course of the imagined barrier.

But it would have to be done in a way that minimizes its impact on navigation and the environment.

"What I would like to learn from this project is, what are the ecological costs of such a barrier, and what would be the ecological opportunities that we could create in building such a barrier?" said UMass Boston marine biologist Lucy Lockwood.

It's too early to say whether a barrier can be done to the satisfaction of the harbor's advocates. But Lockwood says there's a possibility the structures could actually encourage the ecosystem.

"How can we learn to create them such that they are a healthy, robust, resilient, functioning ecosystem," she said, "just as if to say they were, say, a natural rocky shoreline."

At Long Wharf downtown — one spot that already sees regular flooding during high tides -- Kathy Abbott, head of the group Boston Harbor Now, says doing nothing is not an option.

"I think what we don't want to see, now that we've spent $4.5 billion cleaning up the harbor and another $14.5 [billion] connecting our city back to the harbor with the Greenway, we don't want to go backwards in terms of the water quality and the ecological health and well-being," she said.

Abbott says that's because the ecological improvements are the basis for the rebirth happening on the shore today.

Smaller — And Bigger — Ideas

The research could point to smaller-scale, land-based solutions to the threat of rising tides.

"There are a host of local solutions that have multiple benefits," said David Cash, dean of the McCormack School at UMass Boston. "And, that can be built sooner, that can be built at relatively low cost, in contrast to a large technical effort on the scale of a Big Dig."

Researchers already suggest that a large harbor barrier — together with coastal defenses — could be on the magnitude of the Big Dig, the mega-project that put I-93 under the city and created the Rose Kennedy Greenway above. The reference to the Big Dig might not sit well with people still paying interest on a $24 billion project.

"It might be, at the end of the day, the smaller solutions are the ones that make much more sense," Cash said.

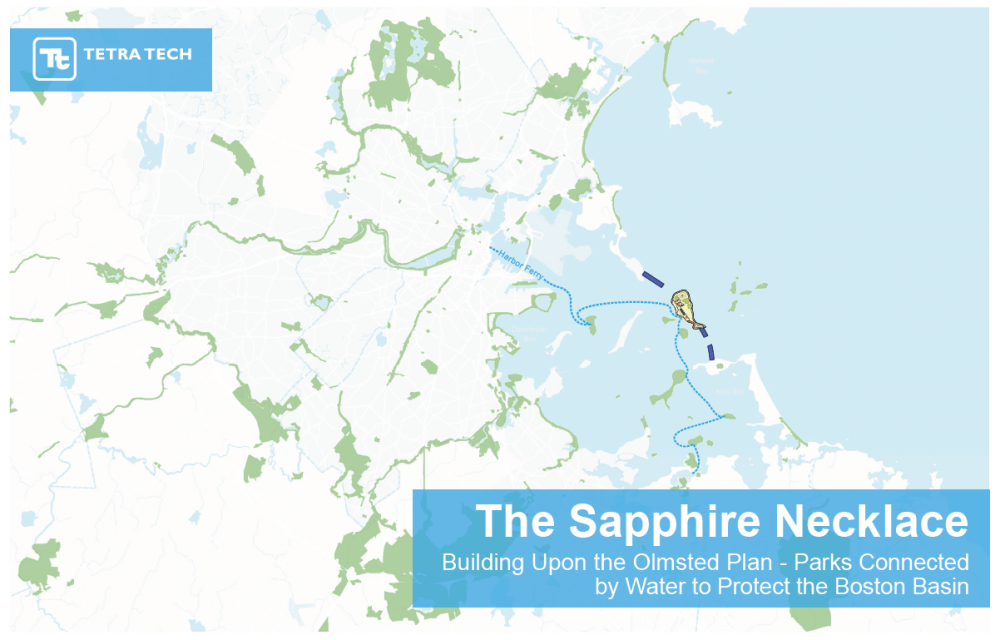

Among early proponents of a harbor barrier is Bob Daylor, an environmental engineer at Tetra Tech in Marlborough. Daylor calls his proposal the "Sapphire Necklace," a harbor barrier that would extend Boston's "Emerald Necklace" park chain into the Harbor Islands.

"There are doubts about cost and, is this really another Big Dig?" Daylor said. "But there is not resistance to the science."

Daylor says until now, American cities have waited for disasters to happen to start planning for future disasters.

"The science says it's going to happen and the question is, does anyone act or do we wait til Sandy happens?" he said, referring to the storm that slammed into New York and New Jersey in 2012. "Or do we act proactively to try to avoid those losses?"

Daylor was alarmed in 2014, when a study envisioned Boston becoming like Venice. The study suggested the city should embrace the water by converting streets into canals. But the notion of surrendering real estate to Mother Nature hasn't gotten a lot of traction.

Another big barrier proposal is called the "Metro Boston Dike Lands." It would expand Boston's real estate by way of a $30 billion harbor barrier from Swampscott to Cohasset.

Peter Papesch, of the Boston Society of Architects' Sustainability Education Committee, says the economic benefits would be twofold: For one, you wouldn't have the interruptions caused by coastal flooding.

"The other one," he said, "is actually creating new land, and paying for such a barrier concept by investors."

It may seem outlandish -- turning water into real estate. But Papesch points out that Boston has done it before — over the centuries — turning the narrow Shawmut Peninsula into the city we know today.

This segment aired on September 6, 2017.