Advertisement

Commentary

How Sundance And Its Attendees Are Getting More Diverse

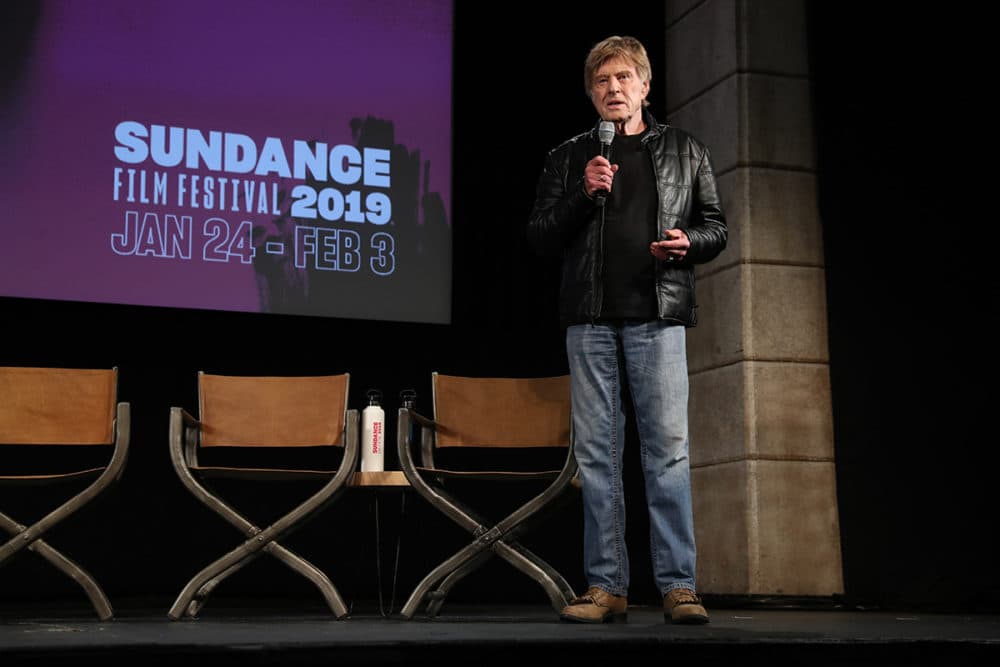

PARK CITY, Utah — "I think we’re at a point where I can move on to a different place," Robert Redford announced to a stunned crowd in his annual introductory press conference at the Sundance Film Festival last Thursday. The superstar founded this event in what was basically his backyard some 34 years ago as a showcase for unsung independent filmmakers, and ever since he’s served as the public face of an institution that has — for better and worse — redefined the landscape of American cinema.

“I’ve been spending a lot of time introducing everything, but I don’t think the festival needs a whole lot of introduction now,” the 82-year-old, sandy-haired screen icon explained. “I think it kind of runs on its own course, and I’m happy for that.” With that, he smiled and walked off the stage an hour earlier than everybody expected, symbolically handing his place at the podium to the Sundance Institute’s executive director Keri Putnam like the passing of a torch.

Redford’s been making a lot of graceful exits lately. Last summer he declared that his twinkly-eyed performance as a gentleman bank robber in “The Old Man & the Gun” would be his last, which is a big loss for film-goers but a fine note to go out on. A few hours after the press conference I watched him welcome folks to opening night, wistfully recounting the festival’s modest beginnings with the aw-shucks air of a guy who still can’t quite believe his luck.

From those humble early days of Sundance rumbled forth an industry earthquake, bringing independent cinema to mainstream attention while kickstarting the careers of Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater, Kevin Smith, Nicole Holofcener and, more recently, Ava DuVernay, Damien Chazelle and Ryan Coogler. Every January, this festival sets the table for the movie year, launching titles you'll still be talking about at Oscar time.

I’ve been coming here since 2012, and the one thing you’re guaranteed to hear from people grousing in line is that the movies aren't as good as they used to be. But the fact of the matter is that with 112 feature films from 33 countries (not counting all the shorts, sidebars and selected television programs) there are at least eight or nine different movies screening at any given moment here in Park City. The festival is simply too massive for anyone to get a read on right away, especially not exhausted, deadline-stressed entertainment journalists trying to chug five or six difficult movies a day at altitude.

For the record, last year’s allegedly "disappointing" lineup included “You Were Never Really Here,” “Eighth Grade,” “Mandy,” “Hereditary,” “Madeline’s Madeline,” “The Death of Stalin,” “Blaze” and “Won’t You Be My Neighbor.” Additionally, four out of this year’s five Academy Award nominees for Best Documentary — “RBG,” “Of Fathers and Sons,” “Minding the Gap” and “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” — all premiered here at Sundance.

But the festival’s outsized influence over the decades obviously hasn't always been to everyone's benefit. Sundance has helped cement the stereotype of an indie film director as a white boy genius with a baseball cap. This legend is often dutifully transcribed by critics like myself, who also tend to be white dudes with beards and baseball caps. “We realized we had a blind spot,” Putnam admitted as last week's press conference.

“Diversity isn’t just about who’s making the films, it’s about how they enter the world. We realized, frankly later than we should have, the implications of the fact that the diverse community of artists here were premiering their work to mostly white male critics," Putnam said. "This lack of inclusion has real world implications to sales, distribution and opportunity.”

Take for instance the 2015 Sundance darling "Me and Earl and the Dying Girl," which took home both the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award despite its ghastly display of racist stereotypes, sexist bromides and unexamined entitlement. Such ugly offenses didn't register on the radars of moneyed Park City crowds or critics comfy enough to take this trip every year, most of whom fell hard for its pandering ennoblement of a solipsistic, spoiled cinephile, and their hype helped it sell to Fox Searchlight for a then-record $12 million.

After the film bombed in general release and was properly curb-stomped by workaday writers, my friends spent weeks afterward asking me what everybody was smoking out there in the snowy mountains. So yes, it matters very much who is watching these films first and setting the narrative for how they are to be unveiled.

And it can get pretty white up here. The first year I came to Sundance, I joked that the only black people I saw for two weeks were Wesley Morris and Spike Lee. (While introducing the cast and crew at the premiere of of his “Red Hook Summer,” Spike announced, “We have just doubled the black population of Utah.”)

But the crowds have been looking a lot more inclusive over the past few festivals, and this year Putnam and her crew overhauled the accreditation process so that a full 63 percent of press passes went to critics from underrepresented groups, with funding from foundations providing stipends to assist some writers with what can be a prohibitively costly trip. It will be interesting to see how these fresh voices help shape the festival coverage. At the very least I have high hopes we’ll be spared another “Me and Earl.”

This year the Sundance Institute partnered with USC Annenberg’s Inclusion Initiative for a fascinating study of artist demographics in submissions and acceptances, which is a long read but full of some very revealing data. This is the first year the U.S. Dramatic Feature Competition has achieved gender parity, with 56 percent of the films directed by women. Among the 61 directors in all four competition categories, 39 percent are people of color.

With all this attention to further diversifying the festival it’s somehow fitting that this year’s first big sale — to Amazon for a whopping $13 million— was “Late Night,” a crowd-pleasing comedy scripted by Boston’s own Mindy Kaling, inspired by her early career adventures as the only woman in a television writers’ room.

Emma Thompson stars as the hilariously brusque and dismissive host of a legendary late night talk show nearing the end of a slow slide to the bottom of the ratings. Kaling shows up as a suburban super-fan with no comedy experience brought onto the all-male staff as a publicity stunt. However formulaic the outline — it’s basically “The Diversity Hire Wears Prada” — Kaling’s screenplay is nonetheless peppered with tart observations about racial resentment and workplace sexism that feel lived-in and true.

But while admirably evolving toward the future, Sundance still shouldn't forget its past. Alas, what should have been a public reckoning fell a bit flat at the premiere of "Untouchable," director Ursula Macfarlane's cogent documentary chronicle of Harvey Weinstein's crimes. Her unflinching interviews with the disgraced mogul's victims are emotionally overwhelming, yet it's tough not to feel like the movie is deliberately avoiding a larger picture. Maybe it was the unsettling frisson of watching a film about a predator on his old hunting grounds, but I wanted more about the culture of complicity that allowed him to flourish in places like this.

It’s sadly telling that there’s no mention of Sundance in Macfarlane’s movie, even though Harvey ruled the roost here for decades during which he presumably committed countless appalling acts. After all, it was only two years ago that during the festival my roommate snapped a picture of Weinstein proudly taking part in the Park City Women’s March. To think of everything that has changed since then is a reminder of how far we have come, and how far we still have left to go.