Advertisement

W.E.B. Du Bois Created These Infographics In 1900 To Humanize The African-American Experience

At the Paris Exposition in 1900, representatives from around the world celebrated achievements like railroads and modern factories and touted the “civilizing” rhetoric of colonialism. However, one exhibit — “The Exhibit of American Negros” — pushed back on the popular narrative at the time.

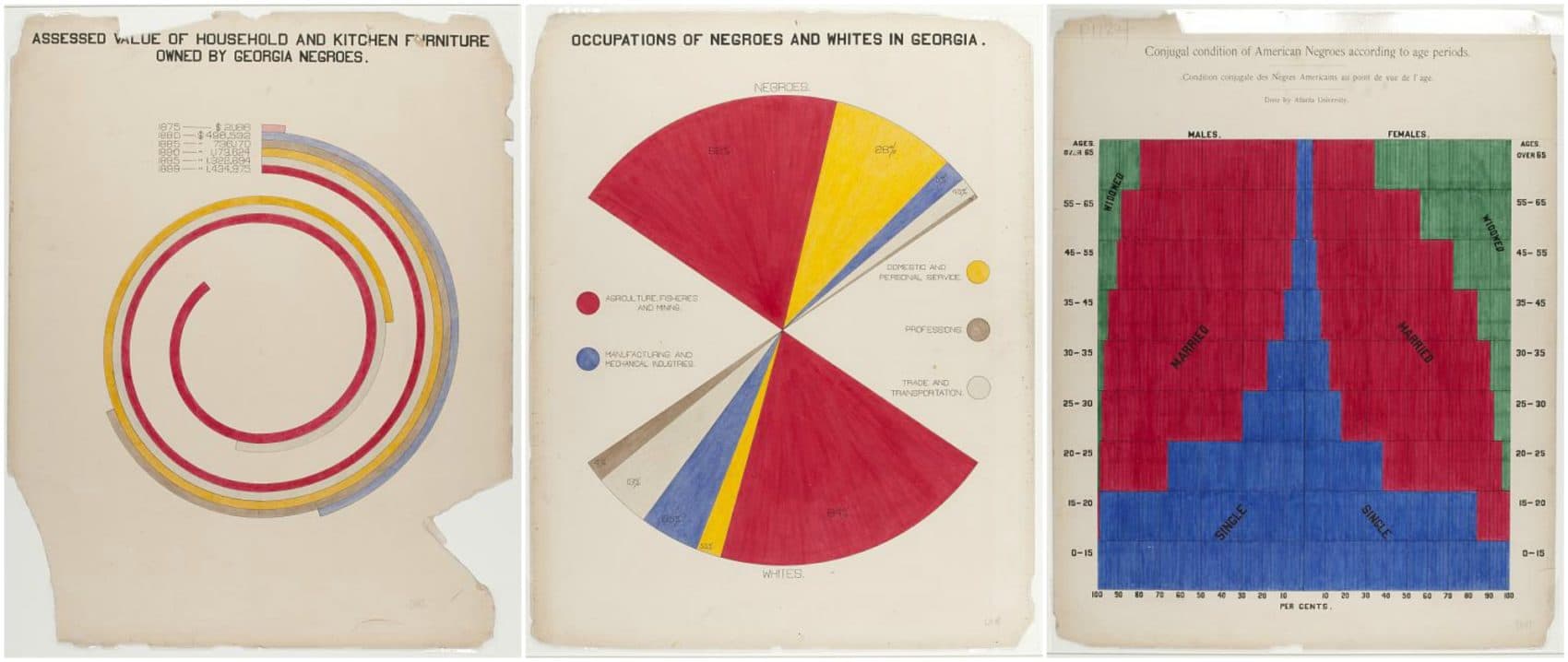

It included 60 data portraits, among other things, that famed sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois created with a team of university students detailing black life in Georgia. Du Bois wanted to challenge ideas about how people of color were operating in the world at the turn of the century and show how blacks fit into America’s progress.

“The dominant narrative at these expositions in terms of nonwhite peoples was ... the representation of people as savages, as people who needed to be uplifted by colonialism, by imperialism,” said Britt Rusert, a professor at UMass Amherst.

She and fellow UMass Amherst professor Whitney Battle-Baptiste published all the infographics together for the first time in October, in a book titled “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America.”

Rusert says at world’s fairs like the Paris Exposition, people of color were often depicted in villages or in jungles, suggesting they had white colonialism to thank for civilizing them. The “American Negro” exhibit refuted those ideas by offering a more humanizing glimpse into African-American life.

Du Bois, along with a team of students and alumni from Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), created these data portraits to put a visual to what Du Bois called the "color line" — a physical and figurative line that divided blacks and whites in the U.S.

In his 1903 book "The Souls of Black Folk," Du Bois used the "color line" as a symbol for the literal racial separation in America and the discrimination and disenfranchisement it caused. (The activist was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and was the first African-American to receive a doctorate from Harvard.) His nuanced writing talks about black people’s existence with a sense of sorrow and despair, describing them as living in the shadows and constantly grappling with what he called "double consciousness" — internal conflict about their place and identity in a racist society.

But the data portraits are different.

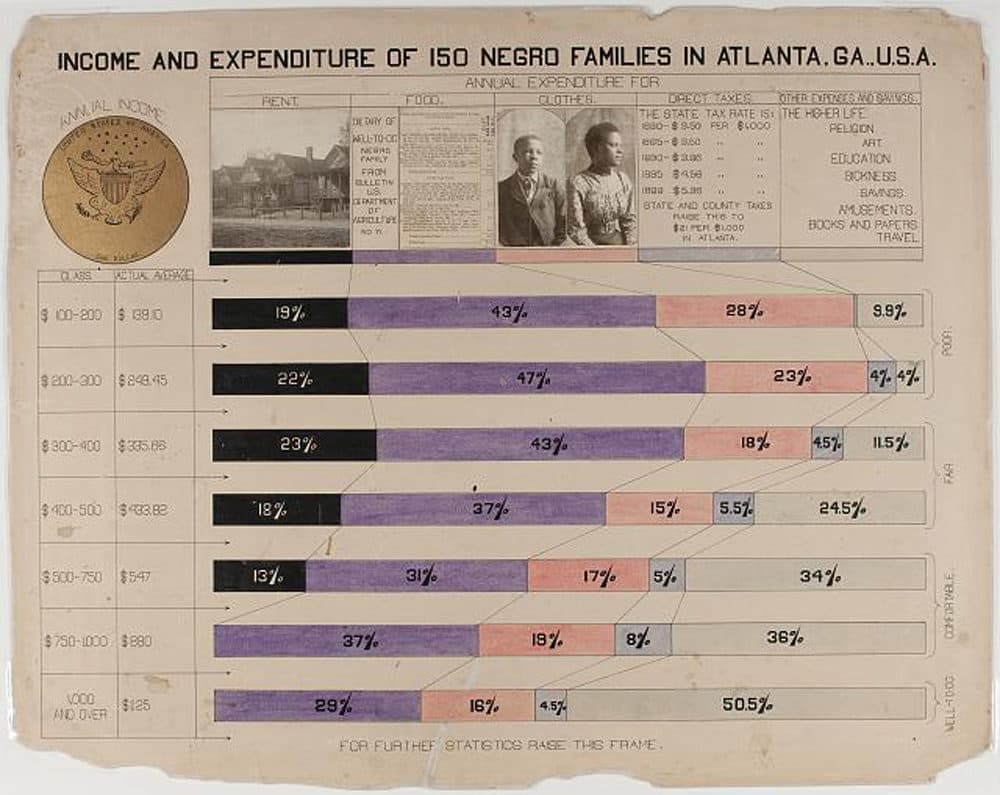

One details the income and expenditure of 150 black families in Atlanta. The families are categorized by class. Pastel-colored and black bars illustrate how much the families spent on rent, food, clothes and other expenses.

As a unit, the data portraits show how race impacted job opportunities and property ownership, but also how African-Americans were making progress post-emancipation. Instead of invoking the dark, shadowy tone of Du Bois’ writing, they use vibrant colors to convey resilience and hope.

“[This] suggests that there's a way out of the bind of double consciousness or that there is a future beyond Jim Crow in a way in which, when you read ‘The Souls of Black Folk,’ ... it's a little bit harder to imagine a way out of that system,” said Rusert.

Though hand-drawn, the portraits appear to look machinic — something Rusert says seems to be a nod to the industrialization and modernization happening at the turn of the 20th century, much of which was made possible by the labor of African-Americans during slavery.

Both scientific and artistic, the designs are bold and eye-catching — something that would have made them easy to interpret by multiple audiences, be they white viewers or African-Americans who may not have known such specific details about their lives.

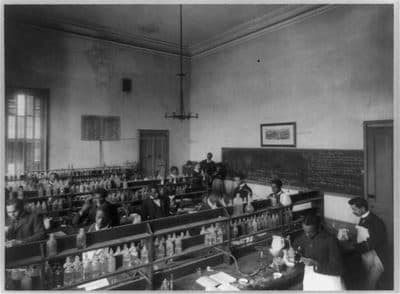

Various aspects of African-American life are captured in the data portraits, which were coupled in the exhibit with photos of African-Americans in the rural south. “They were entrepreneurs. They were students that were in labs at historically black colleges and universities. This was inside people's homes, who were homeowners, who were a part of [a lifestyle] African-Americans often weren't associated with,” described Battle-Baptiste.

She says this is indicative of Du Bois’ effort to make black people relatable.

“You don't have to be a black person to relate to [these stories] and the narratives of people who have lived in the past and how that reflects on our interactions with each other today,” she said.

Rusert says she would love to see how Du Bois would have used the data portraits more than 100 years later.

“It would be kind of interesting to think about those statistics that wouldn't have changed since 1900, and if any of these infographics — if they could still stand today,” said Rusert. She offers that a modern-day version of these portraits might focus on police brutality. “I think there could be some differences but also some really uncanny similarities in terms of the kind of social, political and economic landscape that Du Bois was illuminating in his own moment.”

The portraits remind Rusert of Data 4 Black Lives, a movement made up of activists and data scientists advocating for the use of data a tool for social change. For her, using data to quantify black progress rather than struggle — like Du Bois was doing in his time — is what makes it so powerful.