Advertisement

'The World Is Open To You': Former Flight Attendant Reflects On Helping Break Pan Am’s Color Barrier 50 Years Ago

Resume

It's easy to grumble about airline travel these days — the cramped seats, the stingy food service and flight delays that happen way too often.

It wasn't always this frustrating. Travel by plane used to be the height of glamour and global chic. That was especially true on international flights.

The U.S. airline that flew the farthest and had the reputation as the finest was Pan American World Airways.

On Pan Am flights, the crews fussed over your comfort. There were elegant menus featuring fine wines and gourmet meals.

"All of this was cooked on the airplane," says Newton resident and former Pan Am flight attendant Sheila Nutt as she shows us some decades-old Pan Am menus featuring caviar, oxtail soup and roast duckling. "And we cooked it to your perfection."

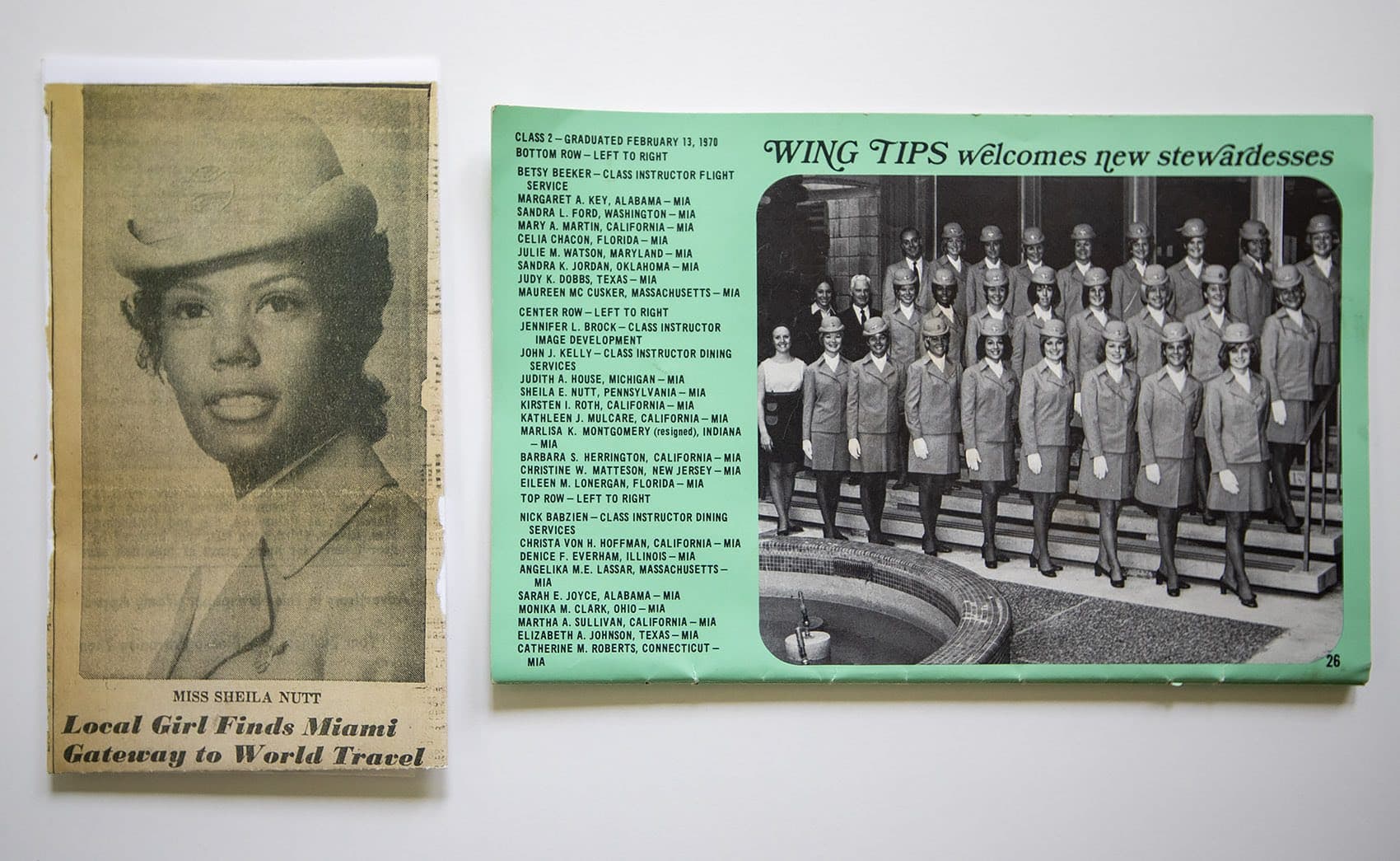

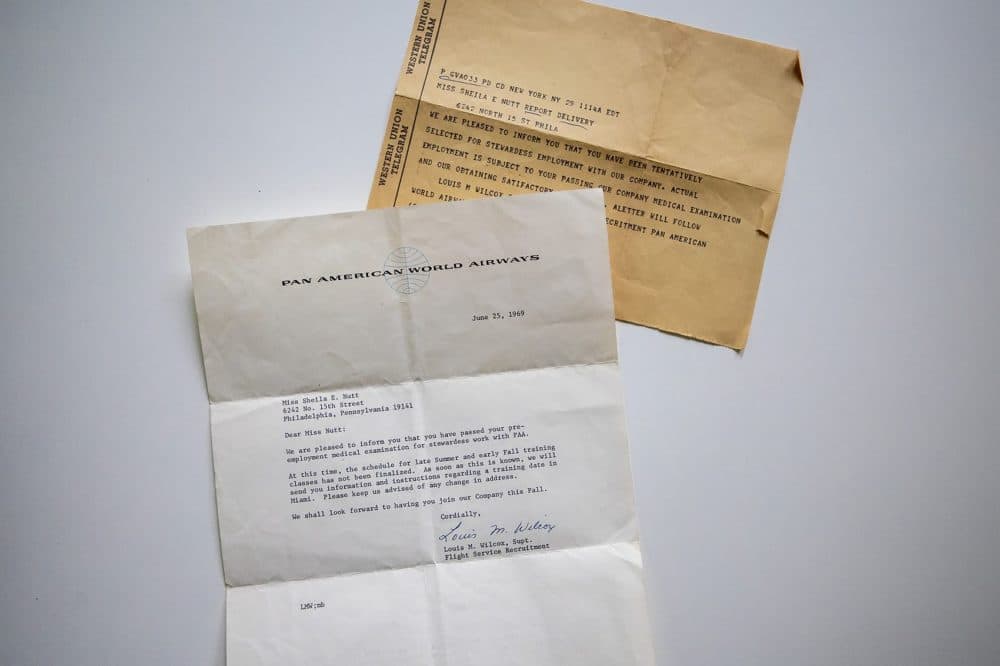

Fifty years have passed since Nutt helped make history. She was part of the first wave of African American women hired as stewardesses, as they were called back then.

A half-century ago, flight crews were mainly white, as were the passengers. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964, airlines had to start hiring people of color. In 1969, Nutt was 20 years old and living in Philadelphia. She heard Pan Am was hiring and wanted in.

"When I went for my interview at a major hotel in Philadelphia and I walked into the room, all of these beautiful blonde, blue-eyed women were sitting there," Nutt says.

She and her friend were the only black women in the room. But racism wasn't immediately apparent. Sexism was.

"Part of the interview was, 'Let me see you walk across the room.' Did you walk like a duck or did you walk like a beauty queen?" Nutt says. "Your teeth had to be straight. You couldn't wear eyeglasses."

You also had to be slim and stay slim if you got the job. Supervisors checked to make sure stewardesses wore girdles. Nutt says that on occasion, there would be random weight checks.

"If you were one pound overweight, you did not get on the airplane," she says.

Nutt had the look Pan Am wanted: She'd competed in beauty pageants. And she was a lighter-skinned black woman.

"I believe that back in the '60s, they were looking for women of color who were not that different from what was considered the norm of beauty," she says. "In the African American community, there was a certain time where they had a brown bag test. There were organizations that would not allow people of color who were darker than a brown bag ... sororities, fraternities, social clubs."

"...most people who had issues around class or color, they were able to restrain themselves on the airplane. Why? Because usually we were in control."

Sheila Nutt

Nutt was hired, and by early 1970 she was up in the air.

On most trips, she was the only black member of the flight crew. She says she rarely faced harassment from passengers.

"You did have your anomaly. You know, somebody ... would get drunk, and then they would say things that were inappropriate, and you knew that they were drunk," Nutt says. "But most people who had issues around class or color, they were able to restrain themselves on the airplane. Why? Because usually we were in control."

One flight to Johannesburg, South Africa, stands out in Nutt's memory. The government there was still enforcing apartheid — the laws of racial separation. Officials told Pan Am that Nutt and the other black members of the flight crew would have to spend their layover at the Holiday Inn at the airport. The white crew would stay at a five-star hotel downtown. The Pan Am pilots and crew strongly objected. And everyone stayed first class.

Nutt says in time, her race attracted less attention.

"As we began to travel the world, we were known as Americans," she says. "Nobody called us black Americans. We were known by the passport we carried."

Asked if she ever felt that her employment by Pan Am was tokenism and only a result of laws requiring racial integration, Nutt says: "I knew I was there because of the law, and it didn't matter."

What mattered to her is that Pan Am paid for her education. She earned her doctorate at Boston University. She started her own consulting business called Flight Attendant Network. Now she works in higher education.

Nutt has organized a group of female African American flight attendants. They call themselves "Blackbirds." They include the pioneers from 50 years ago. And Nutt is compiling a book of their stories of being in the vanguard of racial integration of the airlines.

"We were hired in an industry by a company who didn't necessarily want us," Nutt says. "But we wanted them. We wanted what they had to offer. So we made sure that we were prepared to enter that profession and then to take advantage of what the profession had to offer."

Nutt says her experience carries lessons for young people today.

"We think it's really important for young women to know that although you may not be represented completely in an organization or a profession, that doesn't mean that you don't belong there," she says. "We want to teach young people of all persuasions, of all colors, that the world is open to you ... not just your local community, but you have a contribution. You have an obligation to contribute meaningfully to the world."

This segment aired on November 21, 2019.