Advertisement

At Harvard, Buttigieg Decided The American Divide Could Be Bridged

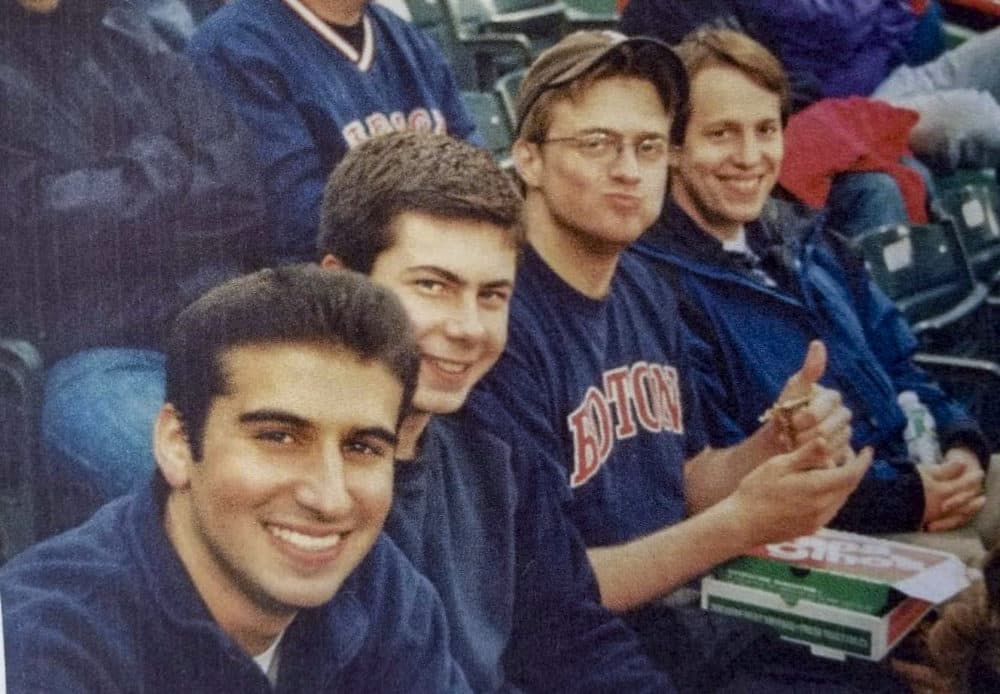

Pete Buttigieg arrived at Harvard in the fall of 2000 as a young Hoosier who didn't necessarily feel like he fit in at the elite East Coast university.

But in his four years at Harvard, Buttigieg would find his place, developing ideas on bridging the divide between Americans, on the future of the Democratic Party, and on American involvement in an increasingly unpopular war.

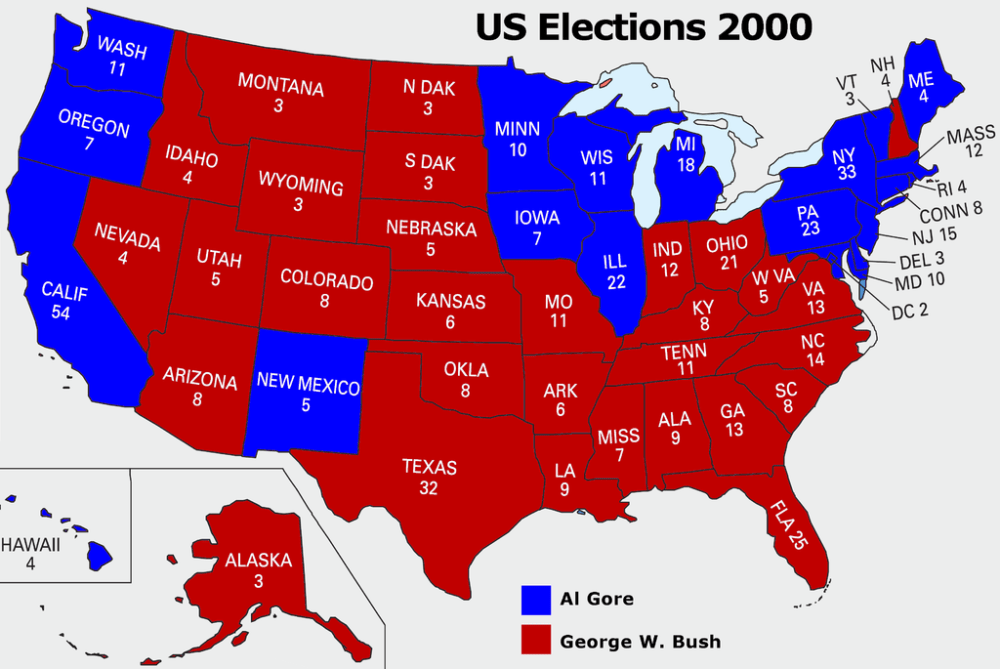

The Map

When Buttigieg arrived at Harvard, the country was divided.

That fall, Al Gore and George W. Bush competed in a presidential race so close it had to be called by the Supreme Court.

Buttigieg, then 18, posted a map of blue and red states on the wall of his freshman dorm.

"He did frequently reference that famous or infamous map," said John Beshears, who lived across the hall. "He thought of it as actually a very striking call to action. He actually viewed it as a source of inspiration to think about: why is it that we see a divide in the country? Does it have to be?"

For Buttigieg, a Democrat from the red state of Indiana, the answer was no, it did not. Settling into his freshman dorm, Buttigieg was already thinking about what could bring a divided country together.

That same year, he began working with pollster John Della Volpe, designing an annual survey of young people. Early on, they found that the greatest number of 18-to-24-year-olds were politically independent. Buttigieg wanted to know more.

"What does it mean to be independent?" Della Volpe remembered Buttigieg asking. He said Buttigieg wanted to know what values drove independent young people. Their research led to them to realize that faith and religion predicted many of those values.

Advertisement

"Concerns about the moral direction of the country, that religion should play a more significant role," Della Volpe said. "They were progressive around protecting the environment, even at the expense of jobs."

They found this was true of one group of young voters in particular.

"What we found was about a quarter or so of this generation was in the religious center, and in some ways, it feels a little bit in terms of where he is today, right?" Della Volpe asked.

Finding A Vision

Buttigieg was raised Catholic. In 2018, however, he married his husband in an Episcopal Church.

Friends say they were aware Buttigieg was religious but don't remember having deep conversations about religion with him. He did talk often about it with one member of the faculty.

"He understood the religious background of this country," said Harvard Kennedy School's David King, who hired Buttigieg as a research assistant for a paper on the Iowa caucuses. "Many of our conversations were about morality and religion and the history of political thought. I remember spending a lot of time with Peter talking about the Democratic Party's unwillingness to embrace religion, especially at the presidential level, and that's something that I think Peter found very troubling as well."

Buttigieg was also troubled by what he saw as the Democratic Party's lack of vision.

"One idea I remember engaging with him about was the notion that the Democratic Party should not simply be an opposition saying, 'Well, we stand for things that the Republican Party does not stand for,' but should instead actually really say: 'This is a positive statement about what we do stand for,' and actually not letting the Republican Party dominate the language of values," Beshears said.

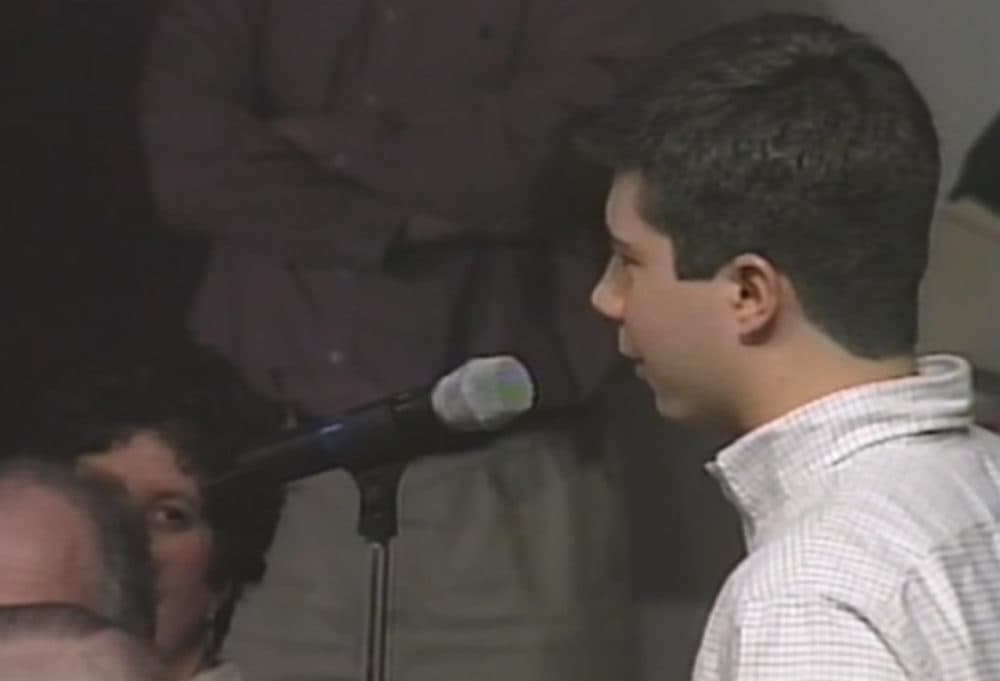

Buttigieg had a chance to put his critique to Senator Edward Kennedy in a forum at Harvard.

"It feels like a lot of your colleagues have adopted a posture of being for whatever the Republicans are for, only less," the 21-year-old junior told Kennedy. "The tax cuts, just a smaller one, and the war, just maybe not quite as quick as the Republican war. And then there are voices like your own which are more forceful in opposition. I wonder if you see this as a split in the Democratic Party and how you think politically speaking, in the next few years, your party is going to sort out what it thinks the meaning of opposition is."

His friend Theresa House remembered having many of these kinds of conversations with Buttigieg.

"And we were all very curious to see who would be the standard bearer of what we hoped would be a transformed Democratic Party, and I think we ultimately saw that after we graduated, with President Obama," House said. "He really came forward and he gave this campaign that was focused on hope. It wasn't just anti- what the Republicans were doing, and I think that Pete certainly seems to have learned from that."

Finding A Place To Fit In

House, from Tennessee, became friends with Buttigieg their freshman year. Part of their bond came from the fact that they both came from places not obviously connected to Harvard.

"I think that he and I kind of shared a feeling of walking into Harvard and just being awestruck by it," House said. "I don't think he felt that he was entitled to be there. It wasn't a natural place for him to show up."

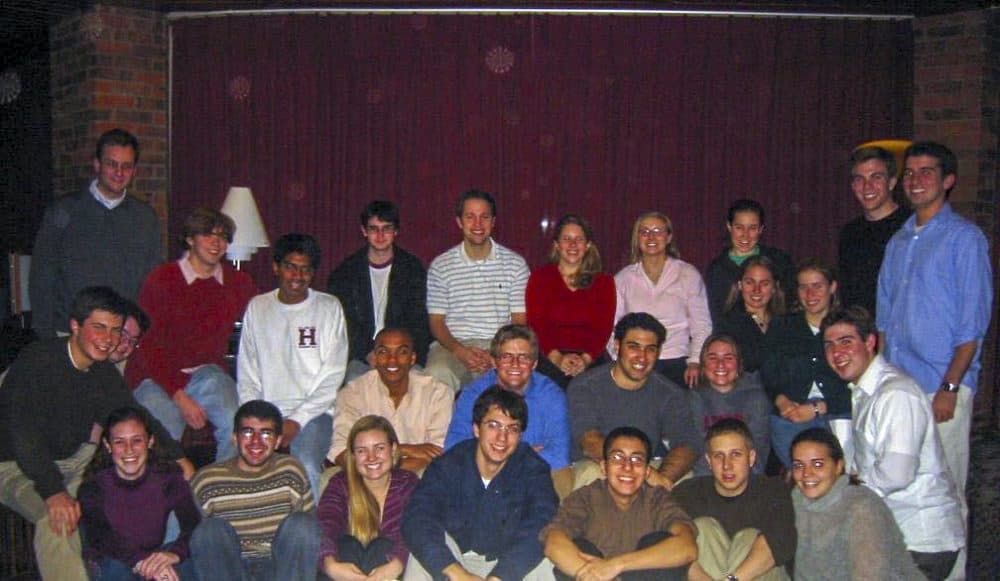

House met Buttigieg through Harvard's Institute of Politics, founded by the Kennedy family to encourage undergraduates to consider careers in politics and public service. It became a Harvard home to Buttigieg.

"In a way, it was like a co-ed fraternity/sorority for political geeks," said Clarke Tucker, who met Buttigieg there.

Some of the most influential people in politics spoke and taught at the IOP on a regular basis, and students held free-flowing conversations about politics.

Tucker was president of the IOP's Student Advisory Committe. He remembers one conversation in which the two talked about whether Buttigieg should run to succeed him.

"It was not about how he could win or what he needed to do in order to win the election," Tucker said. "The conversation was whether he should run and whether he was the right fit for the office and the best person to lead the organization over the course of the next year."

Beshears remembers that by early 2003, as the United States prepared to invade Iraq, the normally reserved Buttigieg found a public voice. The poll he had worked on revealed that most college students supported the impending war.

But he spoke out against it at a rally at Harvard.

"I really admired him for having the courage to get up there and take a stand on an issue that he believed very strongly in when it was not actually, at least to my mind, very easy to make a call," Beshears said.

A Passion For Service

"A lot of people thinking about Peter at Harvard imagine, 'oh, he must have been the most ambitious political person on the face of the earth,' " said King, the professor with whom Buttigieg used to talk about religion in American life. But that's not what King said he saw.

"What I got from Peter was deep concern and deep care about his generation," King said. "Despite leading a very political organization at the Institute of Politics, Peter never came off as tremendously political. It's quite an interesting ability."

It's an impression shared by all the friends and faculty members interviewed for this story: that Buttigieg was not that self-promoting student everyone knew would go into politics, but rather was a reserved intellectual who got along with everyone. At Harvard, he found his voice. His friends expected him to choose public service, but not necessarily politics.

This segment aired on January 17, 2020.